Part 104. Two years of posts!

Part 5 of the official account of the Battle of Britain. Published in 1941.

“MEN LIKE THESE”

When the order to begin the assault on these islands was given, the morale of the German air crews was undoubtedly high. The reason was obvious. For years these young German airmen had been "groomed" for victory. They were assured of their own superiority as individuals and their omnipotence as a striking force. Had they not seen in the first weeks of the spring of 1940 the terrible predictions of their leader come to pass? Each country Germany had attacked had fallen before the crushing blows of the "Nazi war machine, of which they, the Luftwaffe, formed so vital a part. Now, only the British Empire remained inviolate. As those young airmen had swept across Europe from Poland to the English Channel, so they expected to sweep over Britain, subdue her people and prepare the way for an invading army. Disillusion awaited them. As yet, still flushed with victory, they were to see their comrades spin to earth or sea in flames. Nevertheless, let it be said for the German morale, So near it approached to fanaticism, that it never faltered, even when the Luftwaffe was losing seventy, one hundred and one hundred and fifty aircraft during each period of daylight. Certainly the German pilots showed qualities of courage and tenacity; but these were of little avail against the better quality and still higher courage of the British pilots. Even in their hour of defeat some pilots of the Luftwaffe thought that the invasion of Britain might take place at any time and that, if it had to be postponed, it would be successfully accomplished in the spring of 1941. It was not, then, any faltering on their part that caused the daylight attacks to die away.

Of the morale of our own pilots little need be said. The facts are eloquent. They had only to see the enemy to engage him immediately. Odds were of no account and were cheerfully accepted. Only a very high degree of confidence in their training, in their aircraft and in their leaders could have enabled them to maintain the spirit of aggressive courage which they invariably displayed. That confidence, they possessed to the full.

Polish and Czech pilots took their full share in the battle. They possess great qualities of courage and dash. They are truly formidable fighters.

Sky Full of Spitfires and Hurricanes

To read the combat reports, written by the pilots immediately after landing from a fight, is to receive the impression of well-trained young men, conscious of their responsibilities and fulfilling them at all times with resolution and high courage.

"Patrolled, South of Thames (approximately Gravesend Area) at 25,000 feet," runs the report of one Squadron Leader in action on one of the "great" days. "Saw two squadrons pass underneath us in formation, travelling N.W. in purposeful manner. Then saw A.A. bursts, so turned Wing and saw enemy aircraft 3,000 feet below to the N.W. Managed perfect approach with two other squadrons between our Hurricanes and sun and enemy aircraft below and down sun. Arrived over enemy aircraft formation of twenty to forty Do. 17: noticed Me. 109 dive out of sun and warned our Spitfires to look out, Me. 109 broke away and climbed S.E. Was about to attack enemy aircraft which were turning left-handed, i.e., to west and south, when I noticed Spitfires and Hurricanes engaging them. Was compelled to wait for risk of collisions. However, warned, wing to watch, other friendly lighters and dived down with leading section in formation on to last section of five enemy aircraft. Pilot Officer ------ took left-hand Do. 17, I took middle one and Flight-Lieutenant ------ took the right-hand one which had lost ground on outside of turn. Opened fire at 100 yards in steep dive and saw a large flash behind starboard motor of Dornier as wing caught fire: must have hit petrol pipe or tank; overshot and pulled up steeply. Then carried on and attacked another Do. 17, but had to break away to avoid Spitfire. The sky was then full of Spitfires and Hurricanes queueing up and pushing each other out of the way to get at Dorniers which for once were outnumbered. I squirted at odd Dorniers at close range as they came into my sights, but could not hold them in my sights for fear of collision with other Spitfires and Hurricanes. Saw collision between Spitfire and Do. 17 which wrecked both aeroplanes. Finally ran out of ammunition chasing crippled and smoking Do. 17 into cloud. It was the finest shambles I've been in, since for once we had position, height and numbers. Enemy aircraft were a dirty looking collection."

Men like these saved England.

Nor must the ground staffs be forgotten. Their tasks were to "service" the lighting aircraft and to maintain communications, at any cost. Those attached to the fighter aerodromes, East, South-East and South of London, fitters, mechanics, signallers, telephone operators, despatch riders and the rest carried on under heavy and sustained bombing by day and by night. For the first time since William of Normandy set foot on these shores, men and women of England—the Women's Auxiliary Air Force was in the thick of it—found themselves in the front line. They did not fail and the list of awards they won beats witness to their bravery and their endurance. They made it possible by carrying out their duties, sleep or no sleep, bombs or no bombs, for the Fighter Squadrons to confront the enemy day after day until he was defeated.

Of the anti-aircraft batteries a whole story can be written; but this narrative is concerned only with the part played by the Royal Air Force in the victory. Its controllers received most important aid from the A.A. Units. Their shells bursting in black or white puffs against the sky gave to watchers on the ground or in the air invaluable information concerning the whereabouts of the enemy. Moreover, they accounted for nearly two hundred and fifty hostile aircraft in daylight during the period of the struggle.

Shattered and Disordered Armada

By 31st October the battle was over. It did not cease dramatically. It died gradually away; but the British victory was none the less certain and complete. Bitter experience had at last taught the enemy the cost of daylight attacks. He took to the cover of night. For what indeed did the Germans accomplish in all their attacks? At the outset they sank five ships and damaged five more sailing in our Coastal convoys; they next did intermittent and sometimes severe damage to aerodromes; they scored hits on a number of factories which caused production to slow down for a short time. In London they did considerable damage to the Docks and to various famous buildings, including Buckingham Palace. They destroyed or damaged beyond repair some thousands of houses; they killed during the day 1,700 persons, nearly all of them civilians, and seriously wounded 3,360. At night 12,581 persons were killed and 16,965 injured. These heavy casualties occurred during the hours when darkness prevented the enemy from being met and turned back as he was in daylight. They provide a Striking, if ominous, proof of the efficiency and devotion of the fighters of the Royal Air Force. To what height would those figures have risen had there been no Hurricanes and Spitfires on the alert from dawn to dusk engaging the enemy whenever he appeared—resolute, ruthless, triumphant?

Such, then, was the measure of the enemy's achievement during eighty-four days of almost continuous attack. A little earlier in the year the Germans had taken thirty-seven days to overrun and utterly to cast down the Kingdoms of the Netherlands and of Belgium and the Republic of France. What the Luftwaffe failed to do was to destroy the fighter squadrons of the Royal Air Force which were indeed stronger at the end of the battle than at the beginning. This failure meant defeat—defeat of the German Air Force itself, defeat of a carefully designed strategical plan, defeat of that which Hitler most longed for-—the invasion of this Island. The Luftwaffe which, as Goebbels said on the eve of the battle, had "prepared the final conquest of the last enemy—England," did its utmost and paid very heavily for the attempt. Between the 8th August and 31st October, 2,375 German aircraft are known to have been destroyed in daylight. (Throughout this account all figures relating to enemy aircraft concern only those actually destroyed. The number damaged or regarding whose fate complete, evidence proved impossible to obtain has not been given. ) This figure takes no account of those lost at night or those, seen, by thousands, staggering back to their French bases, wings and fuselage lull of holes, ailerons shot away, engines smoking and dripping glycol, undercarriages dangling—the retreating remnants of a shattered and disordered Armada. This melancholy procession of the defeated was to be observed not once but many times during those summer and autumn days of 1940. Truly it was a great deliverance.

It was not achieved without cost. The Royal Air Force lost 375 pilots killed and 358 wounded. This was the price, and of those who died let it be said that:

"All the soul

Of man is resolution which expires

Never from valiant men till their last

breath."

Such was the Battle of Britain in 1940. Future historians may compare it with Marathon, Trafalgar and the Marne.

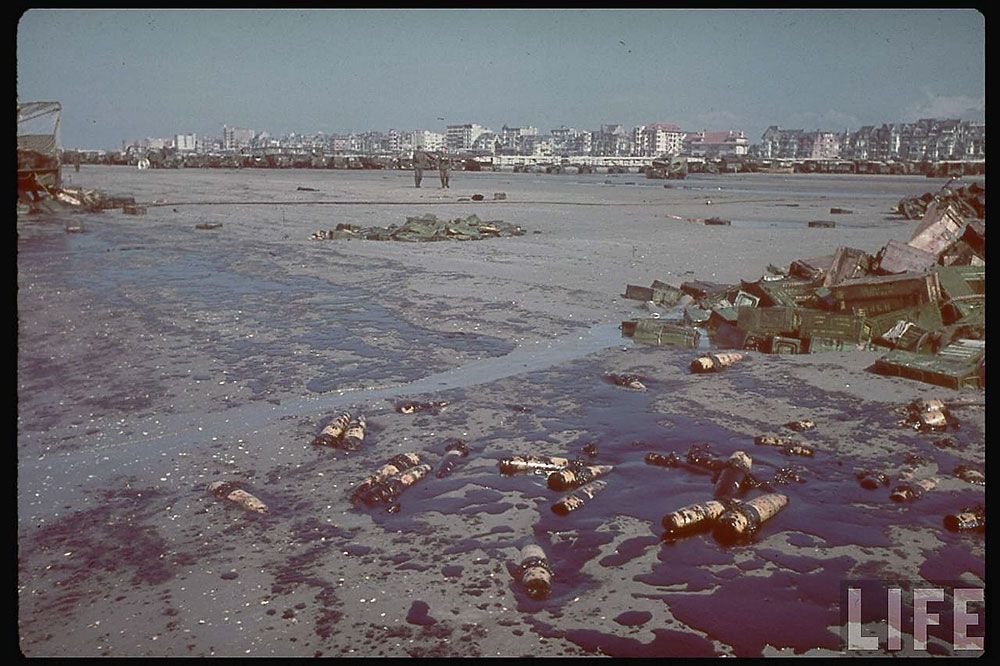

Dunkirk after the battle. Scene of the RAF’s second major encounter with the Luftwaffe. Nothing to do with the Battle of Britain, just interesting LIFE photos I have recently found.