Part 96.

22. Cologne—in Daylight

Six squadrons of Blenheims of bomber command penetrated into the Rhineland this morning to attack the great Cologne power stations at Quadrath and Knapsack. Fighters accompanied the bombers as far as Antwerp. The bombers went on alone, often flying at less than 100 feet, on their 150 miles penetration of the German defence system. Both power stations were attacked at 11.30 a.m. at point-blank range. A great number of bombs scored direct hits and the targets were left in flames. (Air Ministry Communiqué.)

You may remember in the film “Target for To-night" a young airman goes around telling the crews where he thinks they're going. When asked how he could possibly know, he says, " I get around. I get the Gen." Two days before we attacked the power-house near Cologne, everybody on our station was getting around, getting the “Gen." We knew there was something big in the air, but no one was quite certain what it was. In fact, no one had the faintest idea.

We were keyed up when we went into the briefing-room at 6.45 on the morning of the raid, and the Station Com¬mander's opening remarks did nothing to lessen the tension. He started off by saying, “You are going on the biggest and most ambitious operation ever undertaken by the R.A.F." Then he told us what it was. Cologne, in daylight. One hundred and fifty odd miles across Germany at tree-top' height and then—the power-house. We were given the course to follow, the rendezvous with other squadrons of bombers, and the rendezvous with fighters. We were given the parting point for the fighters and the moment at which certain flights would peel off the formation for the attack on the second power-house, and then—in formation across Germany. Our orders were to destroy our objectives at all costs.

While pilots and observers were getting all they could from the weather man, we rear gunners gathered round the signals officer for identification signs and then hurried out to get ready. Someone said, “What a trip!" and got the answer, “Yes, but what a target!”

Knapsack, we were told, was the biggest steam power plant in Europe, producing hundreds of thousands of kilo¬watts to supply a vital industrial area. If we got it, it would be as good as getting hold of a dozen large factories.

One of the pilots on the raid was in civil life a mains engineer for the County of London Electricity Supply. He came away rubbing his hands and explained to us that, with turbines setting up about 3,000 revolutions a minute, blades were likely to fly off in all directions at astronomical speeds, smashing everything and everyone as they went.

We crossed a fairly choppy sea to the mouth of the Scheldt, flying in probably the biggest formation of bombers ever to deliver a low-level attack. It was grand to see them. Even while we were attacking we knew that other bombers and squadrons of fighters were penetrating deep into the Pas de Calais.

Over Holland we saw fields planted out in the pattern of the Dutch flag. People everywhere waved us on, there was a remarkable amount of red, white and blue washing about the place. I saw one Storm Trooper standing over a group of workers, and when he saw us he ran like a weazel. Near the frontier they did not wave, they just watched us. In Germany itself men scuttled off for shelters. During the whole of our trip we saw no motor transport of any kind.

I was sitting in the rear turret and I didn't know we were over the target until I saw the power-house chimneys above me—four on one side, eight on the other. Then the observer called out, “Bombs gone," and as I felt the doors swinging to, the pilot yelled, “Machine gun!” I burst in all I could as we turned away to starboard. Three miles off I had a good view of the place. We had used delayed-action bombs, and banks of black smoke and scalding steam were gushing out. Debris was rocketing into the air, and I thought of those turbine blades ricochetting around the building.

On the way back we kept sufficiently good formation to worry attacking Me. 109's. The first I knew of them was the leading air-gunner calling out: “Tally-ho! Tally-ho! Snappers to port beam. Up five hundred." The attack went on for eight minutes until they broke off and another formation of twelve enemy snappers came into action. They left us when they saw our own chaps coming out to meet us.

Some odd things happened on this raid. One draughty hole in a front perspex was stopped by the gallant observer sticking his seat in it to keep out the gale. Over Holland we flew into hosts of seagulls, and some aircraft brought back specimens stuck in their engine cowling, so giving rise to the suggested Dutch communiqué, " And from these operations five of our seagulls failed to return." Twelve ducks also failed to return; one of our aircraft came back with them inside it, all of them dead. But I should think the oddest things of all must have happened inside that power-house at Knapsack.

When we got back we astonished a few people on our station when we told them where we had been. Sometimes we get around too. We also get the “Gen," and we cer¬tainly got the target.

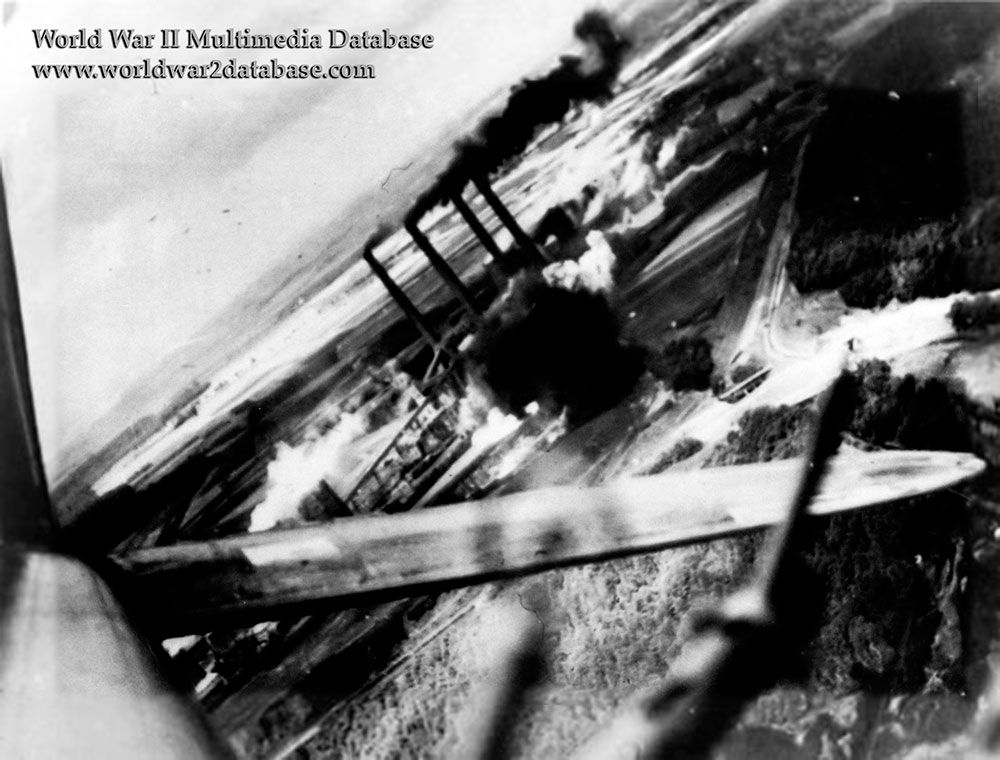

A Bristol Blenheim Mark IV of the Royal Air Force's Number 2 group pulls away after a successful attack on the Fortuna Power Station in Quadrath. You can see the end of the dorsal turret Vickers .303 machine gun lower right. Two power stations, Fortuna I and II, burning lignite (brown coal), were run by Rheinische Aktiengesellschaft fur Braunkohlenbergbau und Brikettfabrikation or RAG (Rhine Public Company for Brown Coal and Briquette Manufacturing) in the small village of Quadrath. Another target was the Goldenberg-Werk Power Station in nearby Knapsack. Fifty-four Blenheims were detailed for a low-level raid, coming in over the Netherlands to attack, causing significant damage. The Blenheims came from 18, 21, 82, 107, 114, 139 and 226 Squadrons, commanded by Wing Commander Nichol in his first Blenheim mission (????-1941) and navigated by Officer (later Wing Commander) Thomas Baker (1914-2006) who later said the mission was "almost suicidal - it was the only time in my life that I saw my fellow aircrew grey and shaking." Ten of the Blenheims were shot down and others were damaged, mostly to the large anti-aircraft concentrations around the plants. The power stations were heavily damaged. While the bomb run on the plant had no fighter cover, Supermarine Spitfires of 306 and 315 Squadrons covered the incoming flight, 308 Squadron with Spitfire VBs and 263 Squadron with Westland Whirlwinds flew top cover, and three other squadrons flew cover for the fighters. 485, 610 and 452 Squadrons, all flying Spitfires, and three other squadrons of Sprtfire VBs struck airfields and targets along the French and Dutch coasts. Lacking the range to get within 100 miles of Cologne, the Blenheims went in on their own; all the Spitfires had to withdraw after five minutes of loitering in the formation area over Holland. 19, 65 and 226 Squadrons, flying the standard short-range Spitfire II, and 66, 152, and 234 Squadrons, all flying the longer-ranged standard Spitfire IIA, rendezvoused with the Blenheims on their return.

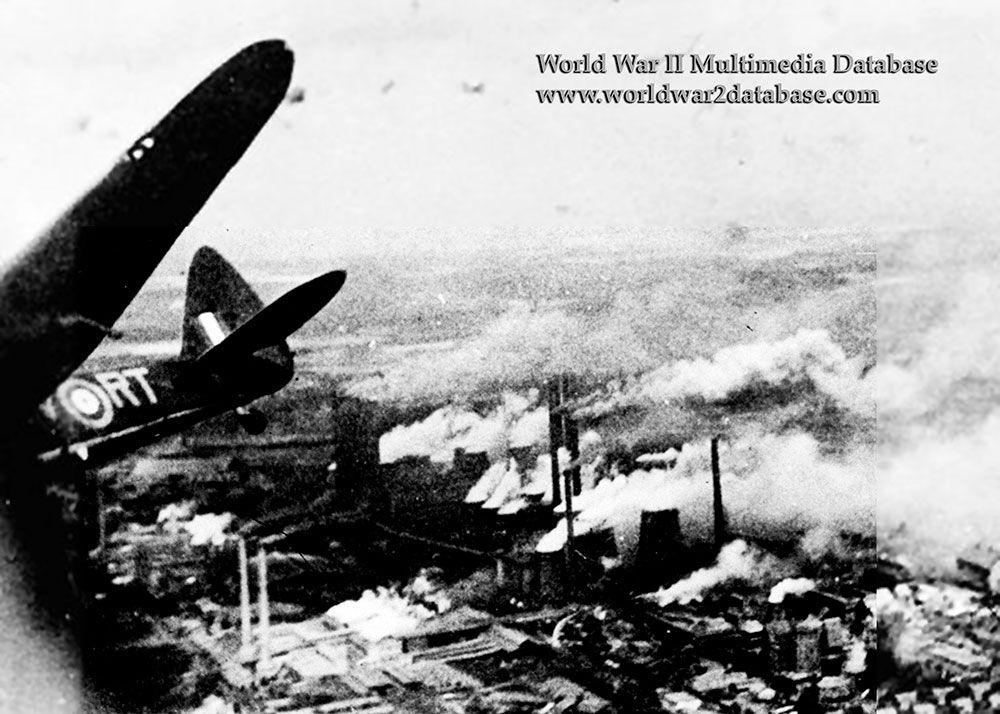

A Bristol Blenheim Mark IV (extreme left), serial V6391, marked RT-V of 114 Squadron, 2 Group, Royal Air Force, banks away after releasing two 500-pound (227-kilogram) bombs over the Goldenburg-Werk lignite (brown coal) power station in Knapsack. V6391, piloted by Sergeant (later Air Marshal) Ivan Gordon Broom (June 2, 1920 - January 24, 2003) and crewed by Sergeant William "Bill" North, Navigator, and Sergeant Leslie Harrison, Weapons Operator and Aerial Gunner. Fifty-four Blenheims made a daring daylight raid on two power stations near Cologne run by Rheinische Aktiengesellschaft fur Braunkohlenbergbau und Brikettfabrikation or RAG (Rhine Public Company for Brown Coal and Briquette Manufacturing). They were escorted by fifteen squadrons of Supermarine Spitfires and 263 Squadron flying Westland Whirlwinds, but none of the fighters had the range to make it all the way to the target, so the Blenheims went in on their own. Broom was noted as one of the flew pilots of 2 Group who did not consider the mission a suicide run. He relished the enthusiastic reaction of the Dutch public, who greeted the low-flying Blenheims with waving and cheers, which abruptly stopped when V6391 crossed into Germany. This photo ran in the Illustrated London News, which syndicated the photo around the world without Brown or his crew being named. The Goldenburg power station was severely damaged, but power was restored to the Ruhr factories. Brown and his crew were sent to the Far East in September 1941, but were "hijacked" in Malta, where they were ordered to fly anti-submarine patrols and attack airfields in Sicily and Italy. On their first flight out of Malta, Broom and North used an Aldis signal lamp to guide a stricken Blenheim back to base. With most of the senior officers dead or missing, Brown was given command and won his first Distinguished Flying Cross, eventually surviving 30 missions. Brown was a popular leader who shared his men's risks.

"Bristol Blenheims" by James Gardner, 1941

This ‘rough' by James Gardiner shows Bristol Blenheims conducting a daylight raid on the German power stations at Knapsack and Quadrath near Cologne, 12 August 1941.

Transcription: ROUGH – In blue pastille. The bombing in daylight of the power station at knapsack Germany by the RAF– Directly beneath picture on right hand side Will be turned upright + a spot more colour in bomb bursts On right hand side with line around – artist's comment