Part 60.

December, 1940

TORPEDOING A GERMAN TANKER

TOLD BY A WING COMMANDER

Aircraft of the Coastal Command of the R.A.F. have had considerable success lately in torpedoing enemy shipping from the air. The commander of a squadron which has been engaged in these attacks, tells you how they are carried out.

THE squadron of Coastal Command which I command has lately had the job of doing from the air what the U-boats attempt from under the sea�that is, the job of torpedoing enemy shipping.

The U-boats which manage to slip past the Navy can find British shipping all over the oceans�we ourselves often fly over huge British convoys during our patrols. But the German ships can only creep along their own coastline, or that of countries which they have occupied, slipping along close inshore under cover of their land batteries and fighter aerodromes, escorted by "flak-ships".

So that's where we have to go to hunt the German ships. If we run across enemy aircraft on the way over, we fight them. We also do reconnaissance, take photographs, and bring back information for the weather people.

But our main targets are German supply ships. They are our big game. And when we find them, we attack them with tor�pedoes, which are slung from the aircraft and launched from the air.

You can take it from me that the squadron scoreboard isn't too bad so far, and although we've only been operating a short time, many thousand tons of German shipping will never see its own harbour again.

The air crews of my squadron, in order to achieve this, fly in all sorts of weather�rain and storm and mist. They cheerfully run the gauntlet of the enemy's coastal defences, flying where the Germans do not always expect to see a British aircraft.

So much so, that when the other day one of our aircraft suddenly swooped through the mist on to a German mine-layer, itself heavily armed and surrounded with flak-ships, the captain evidently mistook the aircraft for a German. For he ran up and down his bridge, flashing the signal "U" at our aircraft. "U" is the International Code for "You are running into danger".

It might have been more appropriate the other way round.

To give you an idea of what this job is like, let me tell you the story of one actual sinking of an enemy ship. It was carried out by a crew of four�the pilot, the navigator, the air gunner and the wireless operator. I would have liked the pilot to give you this talk instead of me. But unhappily that cannot be. The other day, on a similar mission, his aircraft failed to return. He was last seen going into all the shell-fire imaginable to make sure of his aim before releasing his torpedo.

So here is the story of the sinking of an oil tanker, which they carried out only the other day. I telephoned Dick, the pilot, that afternoon in his flight office at the aerodrome, to tell him he was off on a roving commission. Then I met the crew of four in the operations room, to tell them what area they were to search, and to give them all the weather information received from other pilots�actually it was wretched weather, with rain, low clouds, and very poor visibility.

Dick went off to see the torpedo properly shipped on his Beaufort and within an hour they had taken off. They flew over to the Dutch coast, popped into one or two harbours to see what shipping was about, and then set off along the coast-line, periodically dodging bursts of fire from the German shore batteries and flak ships.

They had practically reached the Danish coast, still in this filthy, grey weather, when they suddenly came upon two big German ships escorted by a flak ship. The attack was all over in a minute or so. The pilot headed straight for the larger ship, a 7,600-tonner. He called to his crew that he was about to attack. He and the navigator hastily worked out the ship's course and speed, and the air-gunner was warned to watch out for the run of the torpedo.

Flying a few feet above the water, and at very close range, the aircraft released its torpedo. Then the pilot had to turn violently, only just missing the bows of the ship with his wings, and coming close enough for the navigator to read the name painted on her. About five seconds later the gunner shouted: "Whoopee! We've got her." And then: "Gosh, she's up in flames." They circled round, in spite of flak, and saw the ship ablaze�she was an oil tanker. Flames reached eighty feet above her and smoke 400 feet above that. They brought home a photograph of her, which you may have seen printed in the newspapers. And when they got back, they confessed to me that they had turned the return journey into a sing-song inside their aircraft.

I never saw four fellows better pleased in my life.

Pics of Dornier Do 17s this week.

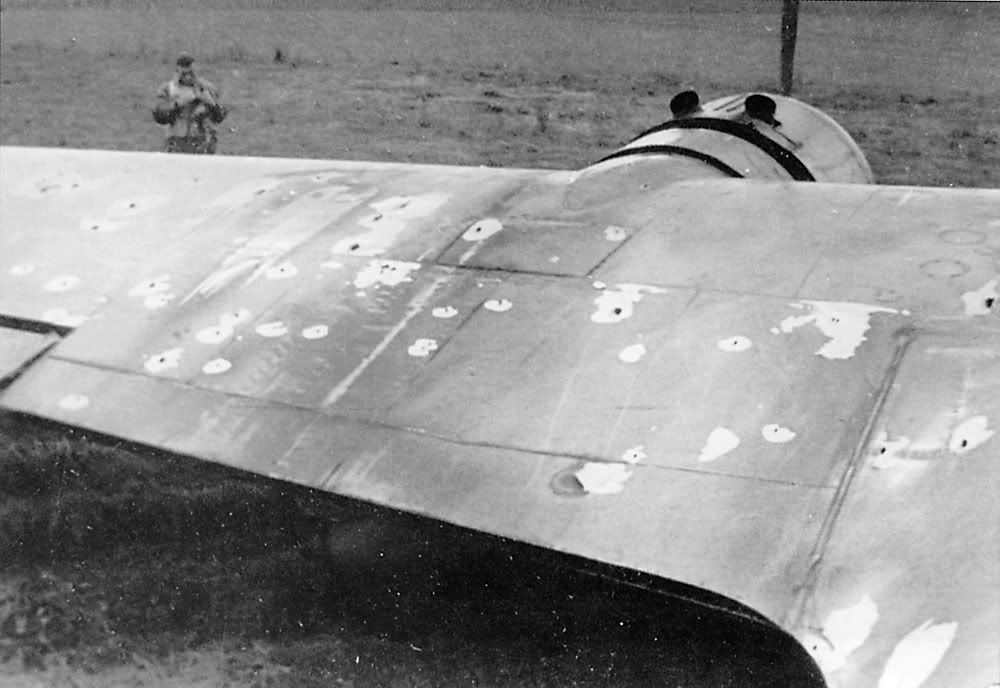

This Do 17 crash landed in France with more than two hundred hits. That number of hits indicates that at least two British fighters fired most of their ammunition into it from short range. On the original print of the wing more than fifty bullet strikes are visible. Indicating the weakness of the .303-in machine guns fitted to British fighters when used against enemy bombers.

Dornier Do 17s in battle formation. The formation was designed to be easy to fly, while providing crews with the greatest possible concentration of defensive fire-power in the all-important rear sector.