Part 37.

September, 1940

MINELAYING BY AIR

BY A CANADIAN PILOT OFFICER

"To the many tasks it is already called upon to perform the Royal Air Force since the war has added a new duty—that of laying mines from the air. Many thousands of tons of enemy shipping have already been destroyed by these mines and here is a Canadian officer of the R.A.F., a young 'veteran" with thirty-six operational flights—as well as the D.F.C.—to his credit, to tell you something of the work of the aerial minelayer."

I THINK I had better start by explaining why anyone wants to lay mines by air when submarines and surface minelayers have been doing the job quite effectively for so long. It's not that we've gone into competition with the Navy on the job, it's just that aircraft loaded with mines, can make their way into narrow roadsteads, shallow channels and even into harbours where no surface vessel could possibly penetrate in the face of enemy defences. Within the past five months aircraft of the Bomber Command alone have laid far more than thirty separate minefields. They extend from Norway to the Atlantic ports, and as fast as a way is swept through any of these fields it is built up again where it will do most good—usually in a busy shipping lane or harbour—and in most cases the only way in which those waters could have been reached at all was by air.

Another advantage of minelaying by air is the speed with which a minefield can be sown. On one occasion there was urgent need for a certain enemy channel six hundred miles away from our base to be mined without delay. We received the order at 6 o'clock one evening. By midnight that minefield had been laid.

Accuracy is all important in minelaying. Unless the mine is placed exactly in a shipping channel it will be practically useless. International law, too, quite apart from the risk to our own ships, requires that mines shall be laid only within the limits of clearly defined areas. Actually we're each given a pinpoint on the chart and that pinpoint is where we've got to plant our mines—or bring them back. It calls for dead accurate navigation and the job's got to be done at night under cover of darkness so that the mines can't be too easily located and swept up.

The aircraft we use are Handley-Page Hampden bombers, but instead of the usual bomb load each aircraft carries a single mine. It's a pretty big mine, a long, fat cylinder about ten feet long and weighing close on three-quarters of a ton, and it packs as big a punch in the way of high explosive as a twenty-one-inch naval torpedo. It can do a lot of damage to even the biggest ship—the wrecks of several ten thousand ton supply ships which can still be seen in the Baltic are evidence of that.

The mine is stowed away inside the bomb compartment and enclosed by folding doors in the underside of the fuselage. There's a parachute attached to the mine and as the bomb doors are opened and the mine falls clear, this parachute automatically opens. It checks the rate of fall so that the mechanism of the mine won't be damaged by too violent a contact with the water. The mine doesn't make much of a splash as it goes in and it drags its parachute down after it to the sea bottom, where it stays put until a ship passes overhead and sets it in action.

Compared with a bombing raid a minelaying trip, of course, is a bit tame from the crew's point of view—almost a rest cure in fact. Being over the water most of the time you don't often get such a pasting from the ground defences as you do on a bombing raid. On the other hand, in a bombing show you do see some results for your money, whereas on a minelaying job it's a delayed-action result and you can only hope that the mine you've brought out and planted with such care will bag the biggest ship left in the German Navy. Still, the job has its compensations. For one thing, we realise how important the work really is. For another, we're given a couple of consolation prizes each trip in the form of two high explosive bombs. After we've planted our mines we can use these on any enemy ships that attack us. We don't often bring these bombs back.

When we first started minelaying our only means of retaliation were our machine-guns, and I remember one occasion in the Great Belt when we sighted an enemy destroyer a few moments after we had dropped our mine. We'd have given a lot for a couple of bombs just then but as we hadn't got them we dived down almost to mast height and shot up the destroyer with every gun we had. Then the destroyer did a bit of shooting up on its own account and I reckon we were lucky to have got away with only one hole in the wings.

Mostly though, minelaying is a much more unobtrusive and restrained affair and the less notice we attract in the process the better we like it. We're allowed to use parachute flares, if we want to, to pick up landmarks, but so far I haven't needed them. I've a grand crew and in the dozen or so minelaying shows we've done together we've usually been able to pinpoint our position fairly near to the minefield. From then onwards it's just a matter of working our way to the particular channel or harbour we want and, having discovered it, to find the exact pinpoint in that channel where our mine is to be laid. At other times, particularly if visibility is bad or the clouds very low, we may be quite a while searching for our pinpoint. Once when the clouds were down to five hundred feet we spent an hour over the Kiel estuary, mostly doing steep turns up and down the stretch of water until at last we spotted the particular square yard of estuary we were looking for.

We've been to Kiel several times. The first time I went mine-laying at Kiel I found it sooner than I had intended. I was feeling my way along the coast after coming out of cloud when I spotted a fjord which I knew was somewhere near the part of the coast we wanted. I turned and flew up it to get my bearings and before I really knew where I was I found myself right over the city of Kiel itself, only 800 feet up and with every gun in the place blazing off at us. I really thought we'd bought it that time—the barrage was simply terrific. I turned right about, put the nose of the machine down and we fairly shot back down that fjord. Then, when things had quietened down a bit, we came back, found our pinpoint in the estuary and laid our mine in the right place.

When we first began minelaying by air secrecy, of course, was of vital importance. Even a mention of the word "minelaying" was forbidden, and, instead it was always referred to in official orders by a code word. The whole secret was well kept and some thousands of tons of shipping were lost before the enemy realised that the mines which sank them had arrived by air. That caution is still second nature with most of us.

Handley Page Hampdens.

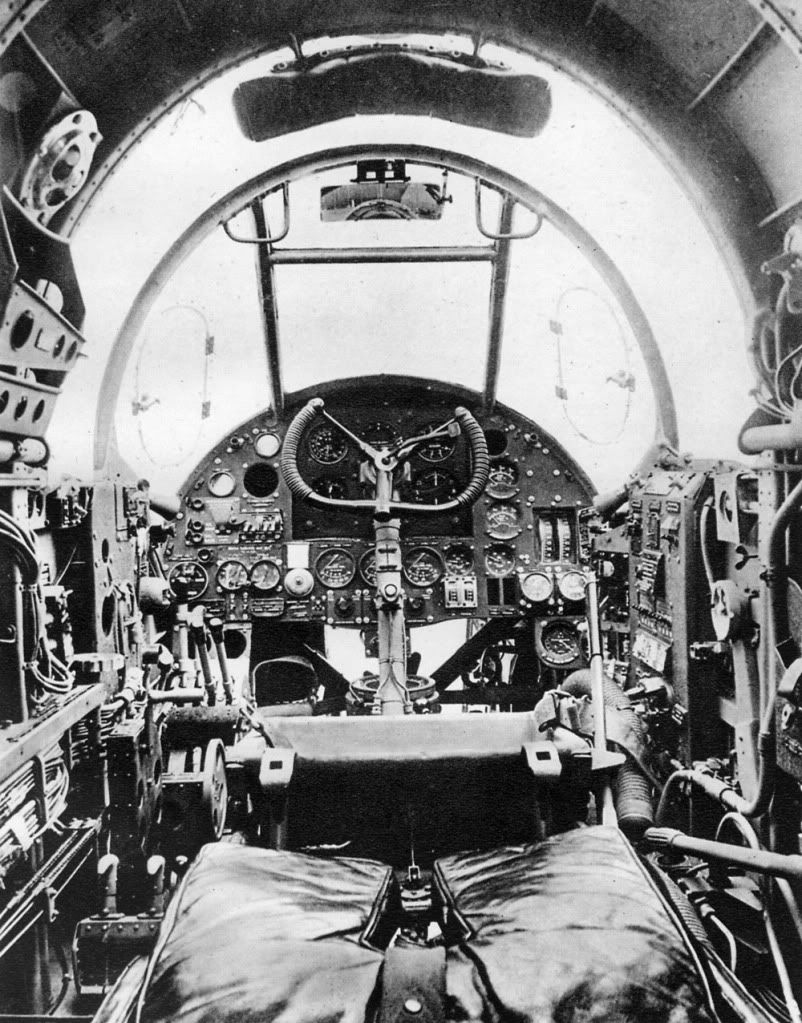

The cockpit of a Hampden Bomber.