Part 95.

21. R.A.A.F. to the Rescue

A very cartridge saved the lives of a crew of an R.A.F. aircraft, when they were drifting in their rubber dinghy in the sea off the south-west coast of Britain. The crew were found by a searching Hudson, lost, and found again and a few minutes later they were picked up by a Sunderland flying-boat of an Australian squadron of the R.A.F Coastal Command, which alighted, and taxied up to them. (Air Ministry Bulletin.)

IT was my flying-boat which picked up the Whitley boys from the Atlantic, but we only came in at the end of the job. If it hadn't been for a spot of good navigation by the Whitley crew themselves, and then by the Hudsons, these lads would never have been found at all.

The Whitley crew sent out their position so exactly when they came down, and the Hudson navigators worked so well, that the leading Hudson was over the dinghy, dropping a bag of comforts, only fifty-nine minutes after taking off. In the comforts bag that was dropped were food, brandy and cigarettes. That's one way to get a smoke these days.

We in the Sunderland were flying towards the last-known position of the dinghy. Then my wireless operator inter�cepted a message from one of the Hudsons:

"Am over dinghy, in position so-and-so."

We altered course for the new position, and at last came upon two Hudsons circling round in steep turns. Soon we got close enough to see the dinghy on the water. It was a dinghy made for only two men, but there were six in it. They gave us a cheer as we went over.

We cracked off a signal to base that we were over them, and then I began to wonder about getting down to pick them up. It's a tricky business putting a big flying-boat down on a roughish sea in the Atlantic. A heavy wave can easily smash the wing-tip floats, or even knock out an engine as you touch down.

We flew around, talking it over, and looking very hard at the sea. It wasn't too promising. The waves were about eight feet from trough to crest. But there was one good point�the wind was blowing along the swell, and not across it.

We soon decided to have a try, and I picked out a comparatively smooth piece of water, about a mile from the dinghy. We landed all right. It was a bit bumpy, but it was all right.

The next problem was to get the boys out of the dinghy and into the flying-boat. We taxied near to them. Two of my crew clambered into one of our own dinghies, at the end of a rope, and tried to paddle across to the Whitley dinghy.

But the rope was too short.

We tied another piece of rope on the end. It was still too short, even then.

One of my crew then climbed out on the Sunderland's wing and fastened the end of the rope to the wing-tip. But by that time the Whitley dinghy had drifted away, out of reach.

Then I thought we would tow our dinghy up to the Whitley's dinghy. We started up the engines, and moved off slowly, pulling our own dinghy along behind us. I'm afraid the lads in my dinghy got a bit wet.

After a few minutes we brought both the dinghies together. They floated alongside the Sunderland itself.

The Whitley dinghy seemed to be very crowded. When I took the crew aboard, I learned that their big dinghy had failed. So all of them had had to cram into the smaller one, which is designed to hold only two men.

We pulled them aboard through the after-hatch of the Sunderland�and just about time, too. Their dinghy was gradually filling with water, and I doubt whether it would have lived through the night. It was only half an hour before dusk when we picked them up.

They were quite all right, though. Just a bit tired. We gave them some hot tea and some food, and they turned in for a sleep on the way home.

We did get one bit of amusement before we got back to base. . . . About thirty miles off the coast we saw beneath us one of the high-speed rescue launches, haring out towards the position where we had picked up the crew.

We flashed a signal to the launch: "Have picked up six air crew from dinghy in position so-and-so."

The launch flashed back only one word: "Blast!" and turned round and headed for home.

Just one other point strikes me about this rescue incident. It had a fine international flavour.

The British crew in the dinghy included one New Zealander. They were located by Lockheed Hudson aircraft built in California. And they were picked up by a flying-boat manned entirely by Australians. There seems to be a nice touch of co-operation about that.

Pics on a seafaring theme, but nothing to do with air-sea rescue:

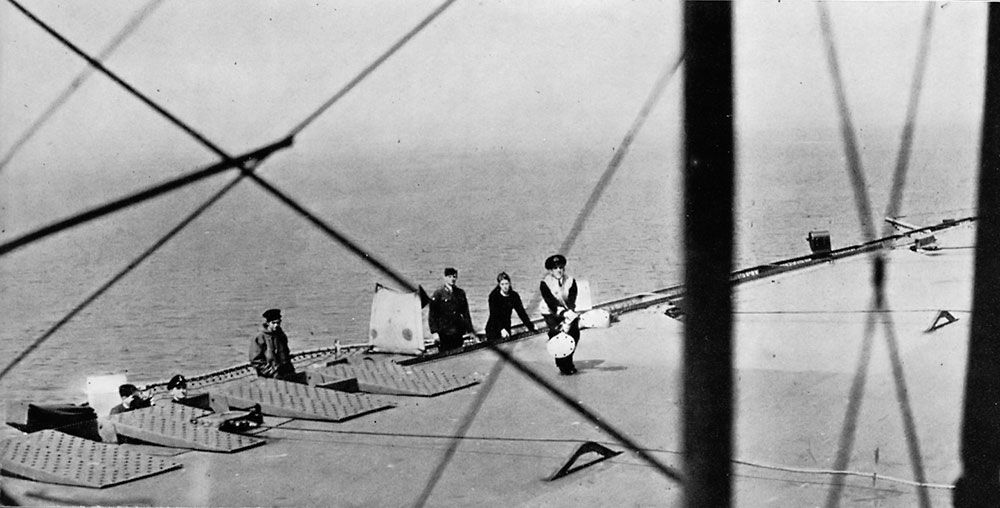

The view a pilot has while coming in to land on one of the new Escort Carriers. Photos taken from a Swordfish.

Four hundred yards away.

Fifty yards to go. The Deck Landing Control Officer signals the pilot that he is satisfied with his approach. Note how the nose of the aircraft is held well up.

Only a few inches above the deck. The Control Officer gives the pilot the signal to cut his engine. Instant obedience is essential if the hook at the back of the aircraft is to pick up one of the arrester wires seen in the foreground.