Part 98.

From ‘Raiders Overhead a Diary of the London Blitz’ By ARP Warden Barbara Nixon published in 1943.

Excerpt from Chapter 3 ‘First Blood’.

My first incident occurred one afternoon in the second week. A soldier, however highly trained, will yet be apprehensive about his own reactions when, for the first time, he actually comes under fire. I had been fairly confident that I could behave reasonably well under gunfire and bombing, and the first seven nights had, more or less, justified my confidence. But what I was very unsure of was what my reactions to casualties would be. I had never seen a dead body, I was even squeamish about handling dead animals, and I was terrified that I might be sick when I saw my first entrails, just as some people cannot stop themselves fainting at the sight of blood. At later incidents one forgot oneself entirely in the job on hand. But on this occasion, because I was unsure of myself, I was acutely self-conscious, and, as a protection, adopted as detached an attitude as I could. I had to watch myself, as well as the objective situation.

It was a grey, damp afternoon in late September, ten days after the start of the air-blitz on London. I was bicycling along a shabby street in a district some miles from my own. The day alerts were so frequent that it was difficult to remember whether the last wailing of the siren had been the alert or the ‘all clear.’

It was a street of narrow houses, so decrepit that they might well have crumbled to pieces had they not been held up by occasional large office buildings, and even these were dingy and decayed. Dirty shop windows announced that they were high-class laundries, or would mend your boots while you waited, or would buy cast-off clothing. The whole derelict street and the lanes leading into it were calling for the house-breaker. A little further on, however, in a side turning on the right, the LCC had made a start, and a block of balconied workers' flats had been erected. They were well designed, and the plaster facings and the brickwork were still unsooted by London's grime.

Suddenly, before I heard a sound, the shabby, ill-lit, five-storey building ahead of me swelled out like a child's balloon, or like a Walt Disney house having hiccups. I looked at it in astonishment, that bricks and mortar could stretch like rubber. At the point when it must burst, the glass fell out. It did not hurtle, it simply cracked and dropped out, allowing the straining building to deflate and return to normal. Almost instantaneously there was a crash and a double explosion in the street to my right. As the blast of air reached me I left my saddle and sailed through the air, heading for the area railings. The tin hat on my shoulder took the impact, and as I stood up I was mildly surprised to find that I was not hurt in the least. The corner buildings had diverted the full force of blast; indeed, to judge by the number of idiotic thoughts that raced through my head, my progress to the railings might almost have been in 'slow motion.' I had not heard any whistle of the bombs coming down, only the explosion, and now the sound of an aeroplane's engine starting up. I thought, 'So it's true—you don't hear the one that gets, or nearly gets, you.'

For no reason except that one handbook had said so, I blew my whistle. An old lady appeared in her doorway and asked, 'What was all that?' I told her it was a bomb, but she was stone-deaf and I had to abandon bawling for pantomime of a bomb exploding before she would agree to go into a surface shelter. After putting a dressing on some small cuts on a man's face, I turned back towards the site of the damage. I did not know the locality, but, again, the handbook said that when an alert sounded, a warden away from his home area should report to the nearest Post. The damage was thirty yards away, but the corner building, which had diverted some of the blast from me, was still standing.

At four in the afternoon there would certainly be casualties. Now I would know whether I was going to be of any use as a warden or not, and I wanted to postpone the knowledge. I dared not run. I had to go warily, as if I were crossing a minefield with only a rough sketch of the position of the mines—only the danger-spots were in myself. I was not let down lightly. In the middle of the street lay the remains of a baby. It had been blown clean through the window, and had burst on striking the roadway. To my intense relief, pitiful and horrible as it was, I was not nauseated, and found a torn piece of curtain in which to wrap it. Two HE bombs had fallen on the new flats, and a third on an equally new garage opposite. In all this grimy derelict area, they had struck the only decent habitations.

The CD services arrived quickly. There was a large number of 'white hats,' but as far as one could see no one person took charge, and there were no blue incident flags. I offered my services, and was thanked but given nothing to do, so busied myself finding blankets to cover the five or six mutilated bodies in the street. A small boy, aged about 13, had one leg torn off and was still conscious, though he gave no sign of any pain. In the garage a man was pinned under a capsized Thorneycroft lorry, and most of the side wall and roof were piled on top of that. The Heavy Rescue Squad brought ropes, and heaved and tugged at the immense lorry. They got the man out, unconscious, but alive. He looked like a terra-cotta statue, his face, his teeth, his hair, were all a uniform brick colour.

Eleven had been killed but a larger number were badly injured— an old man staggered down supported by two girls holding a towel to his face; as we laid him on a stretcher the towel dropped, and his face was shockingly cut away by glass. It was astonishing that he had been able to walk down stairs. Three more stretcher cars and two ambulances arrived, but they had to park some distance away because of the debris. If they had been directed to approach from the western side they could have driven much closer. The wardens began to check up the flats. As I did not know the residents, or how many of them there ought to be, I could not help, and stayed below.

But by now the news had travelled, and women back from shopping, girls, and a few men from local factories, came running and scrambling over the debris in the street. 'Where is Julie?' 'Is my Mum- all right?' I was besieged, but I could not help them. They shouted the names of their relatives and scanned the faces of the dusty, dishevelled survivors. Those who found that they had lost a relation seemed numbed by the shock and were quiet, whereas a woman who found her family intact promptly had hysterics. The sudden relief from an awful fear was more unnerving at the moment than the confirmation of the fear.

A little later I left: there was nothing apparently that I could do, little enough that I had done. Any bystander could have been as helpful as I had been, and I felt discouraged and depressed. My bicycle was bent, but since the wheels would still go round, I clanked and wobbled on it back to my own Post.

Tommy Brickman was there, and greeted me with 'Blimey, your face!' I explained how it had got so dirty, and noticed, to my amusement, that he was obviously chagrined that it had been I, and not himself, who had 'had the fun.' Tommy was an energetic and conscientious warden, but both imaginative and loquacious. His existence was a continuous conversation piece with no back answers allowed. At the same time, he was quite incapable of seeing only six German planes, or being missed by only a 50-kg. bomb, or of extinguishing only a dozen incendiaries; it had always to be 60 planes, a 1,000-kg. bomb, or hundreds of incendiaries at least. If Tommy went away for a day or so to another town, we knew that that town would have 'the biggest blitz ever.' If he travelled by train, that train was machine-gunned. It was a habit that irritated the more serious-minded members of the Post, though I could not myself see that it mattered whether Tommy's graphic and hair-raising accounts were in fact true or not. I think he found me a pleasant audience, as I always egged him on by asking innocent questions. However, this time it was my story.

Tommy made me some tea, but before we had time to drink it, the evening siren went, and I left for my sector post. It was another all-night session and the 'all clear' did not sound until 6.15 a.m. We were supposed to wait, however, until we received the 'white' on the telephone, and I waited irritably for half an hour, angry with Control for being so inconsiderate of us after a twelve-hour raid. But when the man who lived in the flat above our post came down, he pointed out that Jim Mackin, the Post Warden, had come round at midnight to tell me that the phone was out of order.

To my alarm, I found that I could not remember that, or anything else after reporting for duty at 6.30 p.m. I replied, 'Oh yes, of course,' but as I walked home I tried to reconstruct the evening. I remembered the incident in the afternoon, but the twelve hours after that were a complete blank; I could not even remember whether I had gone home for supper. I counted the plates in the kitchen, but that did not tell me anything, and I was really frightened as I waited for someone in the house to get up. For all I knew I might have made an awful fool of myself. Apparently, I had behaved quite normally, made my usual tour of the shelters, had supper, and helped someone to change the wheel of his car, but I still could not remember any of it. I had one hazy picture of a white hat in a doorway, which must have been Jim Mackin, but that was all. If I was to have that sort of reaction after every incident, it was going to be inconvenient.

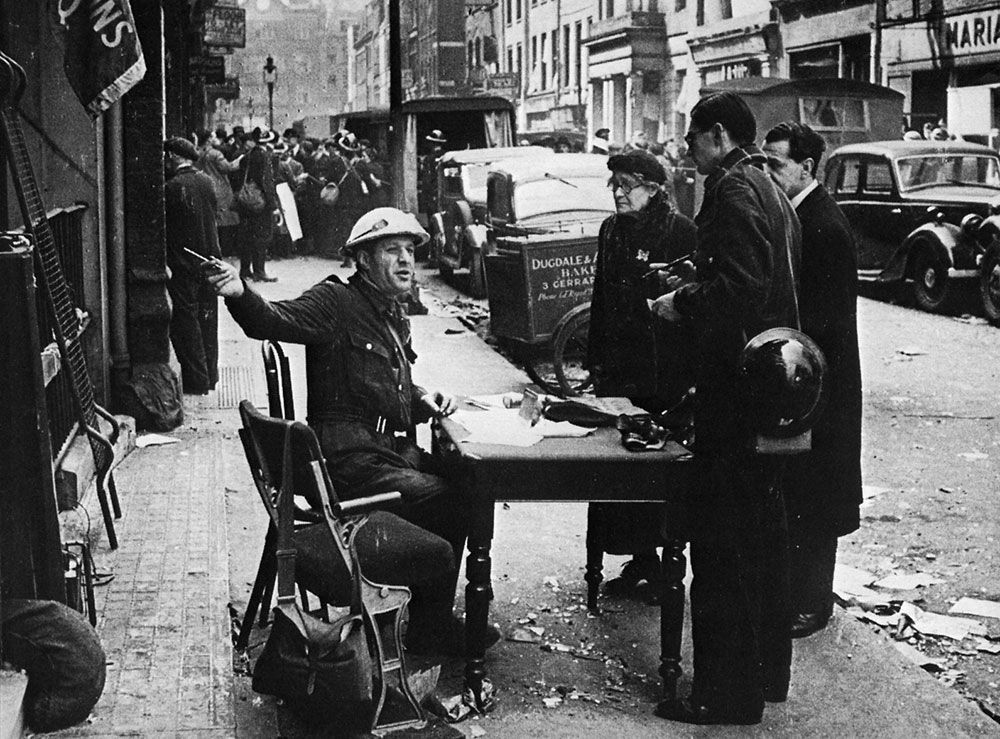

The ARP post open for business in the street.

Finsbury ARP post number 2 1941.