Part 65.

STORY BY A CANADIAN SPITFIRE SQUADRON LEADER

The author of the following account is a young fighter pilot of whom Canada may well be proud. To-day the leader of an R.A.F. Spitfire squadron, he had flying in his blood ever since he went to school in Winni¬peg, Manitoba. He made his first flight when he was fourteen, and he learned to fly an aeroplane two years later. At seventeen, he was the youngest licensed flyer in the Dominion and when he got his commercial licence, two years later, he was the youngest commercial pilot. So he sailed for England in 1935 to join the R.A.F., and within a fortnight of his landing in Liverpool he was in the Royal Air Force. Before the war started he had been awarded the Air Force Cross for a particularly dangerous job of flying. Just recently he won the Distinguished Flying Cross, for gallantry in action as the leader of a Spitfire fighter squadron.

WELL, I've been lucky enough to see quite a lot of this war so far, and believe me, I hope I'm going to see a lot more of it before it's through. I want to see, for instance, another afternoon like that of September 27th, when the R.A.F. slapped down more than one hundred of Goering's Luftwaffe.

At the time I was a flight commander in the now famous Polish squadron, flying Hurricanes, and with several other squadrons we went up to meet the Germans. A terrific anti-aircraft barrage was being put up round London, and from where we were we could see the capital gradually become encircled by a ring of smoke puffs from the bursting shells. Then we saw the hordes of German bombers and escorting fighters coming in over Kent. As R.A.F. fighters got stuck into them, you could see them falling away, plunging down with smoke pouring from them. It almost seemed that there was an invisible barrier over a certain part of Kent and that as soon as the bombers reached it large numbers of them suddenly began pouring out smoke and going down. It was an amazing sight and if I hadn't seen it all happen, I would never have believed it.

All this was happening in the few minutes before we arrived. Our squadron, by the way, was accompanied at the time by a Canadian Fighter Squadron, so I felt quite at home as we went into battle. I got behind one bomber and went straight in at him. When I was about seventy-five yards from his tail, his rear gunner suddenly realized that I was there and opened fire. I fixed him with my first burst. Then I pressed the gun button again and kept my thumb on it for several seconds, and shortly afterwards he began to go down in flames. I watched him and saw him go into the sea with an almighty splash.

Another German bomber which crossed my sights got a quick burst from another pilot and as he went gliding down I saw a red glow appear under his belly, and as the glow got bigger, so his dive got steeper. He exploded before he hit the water, and it began raining little pieces of aeroplane from the spot where he had blown up.

There was a lot of milling around in the sky that afternoon, and when the Canadian squadron and ourselves got back we found that we had collected more than a dozen Huns between us. The day's score, as I said, was over the hundred mark. I got two bullets in my Hurricane that day, and they are the first bullet holes I have had in my aeroplane since the war started and I hope the last.

I want to tell you right now that it was a grand experience fighting with the Poles. When the squadron was first formed at the end of July the nucleus consisted of an English Squadron Leader and two flight commanders, of whom I was one. The Poles who came along had plenty of fighting experience. They had fought in Poland, and later in France, and when we got together in the early days of August we were all flat out to have a crack at the Huns. By the end of the month we had taken our place in the front line.

The first morning in the front line we were sent to escort a formation of our bombers; we ran into a raid and we got a Dornier 17 first crack. The next day we got six Messerschmitt 109 fighters, and from then on we slapped 'em down as they'd never been slapped before. In their first four weeks that Polish squadron shot down more than one hundred enemy aircraft, and in five weeks we had shot down more than one hundred and twenty.

You can take it from me that those Poles were magnificent fighters—and they still are. They introduced their own technique into air fighting. They sailed right into the enemy, holding their fire until the very last moment. That was how they saved ammu¬nition and how they got so many enemies down on each sortie.

When I started talking, all sorts of incidents come crowding into my mind about this war. I was in France doing a special job in a Spitfire from May until June 16th. Just before the French collapse I remember flying over one part of the country in which there was not a single living thing. Not a head of cattle, not a dog, and certainly not a human being. And then I came upon the refugees and saw, for mile after mile, roads packed tight with people, fleeing before the Germans. At one stretch I should say there were forty miles of road packed solid with refugees.

There were tragic sights to be seen on the ground, too. In every hotel the people were lying about all over the place, just snatching a little sleep before moving on. I remember, particu¬larly one old woman, with all her worldly belongings in an ancient perambulator. Yet she had a cage hanging by the side of the pram, and in the cage was her cat. They were pitiful sights, but the French were very brave. I got on very well with them, largely, I think, because I am a Canadian. Before, and even after the collapse, you only had to say you were a Canadian and there was nothing that the French would not do to help you.

Since I've been back in England I've had my share of excite¬ment—and when it's been in the air it's always been most enjoy¬able. Some days ago, for example, we saw between sixty and eighty Me. 109s, and though there were only five of us Spitfires at the time, we had a height advantage of some 6,000 feet. We just nipped down on them. The one I got first began to belch black smoke and went streaking down, leaving a tremendous trail of smoke that stayed in the sky for at least ten minutes. Then I had a terrific dog-fight with another Messerschmitt which attacked me immediately afterwards. He could fly, too, could that Hun. He kept swinging up and round into the sun and several times I had to guess where he was as he disappeared with the sun right behind him. I squirted at him several times like that and finally saw him come out of his protecting sunshine with his tail nearly off.

The fin and rudder were in tatters. As we rushed towards one another I could plainly see the pilot looking straight at me. We missed each other by feet. As he turned to the left he made a target of himself, so I squirted him for a second. He flicked over on his back and with grey smoke simply pouring out, went straight down towards the Kentish soil. He went into the ground with an awful smack. There was a flash of flame, a cloud of smoke, and when I looked again there was nothing but a gaping hole with a few tiny pieces of scattered wreckage round the edges. I saw some British Tommies run across to the crater he had made and look down. Then they waved up at me and gave me the thumbs up sign.

Well, that's the kind of job we're doing and we get quite a kick out of it. Of course, you don't run into Huns every day of the week, but when you do go up to meet him you feel so good that you think you could take on the entire German Air Force single-handed. These Spitfires we're flying may account for some of that feeling—they're certainly good. Altogether now I've done about one hundred and fifty hours' operational flying in this war and I only hope there's going to be a lot more to come.

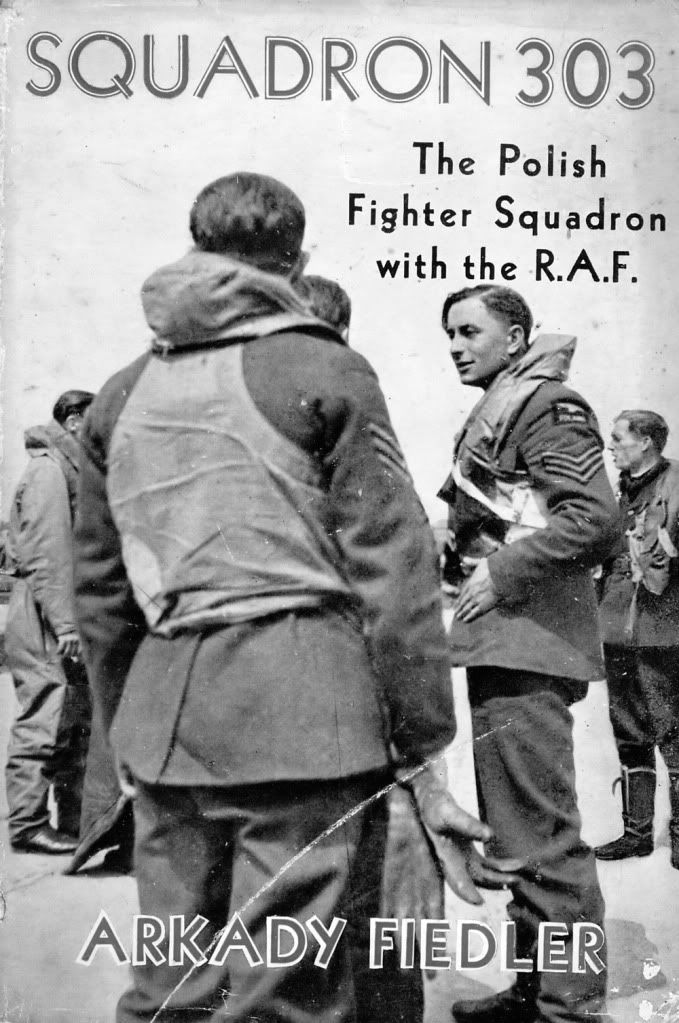

Pilots of 303 Squadron ‘The Polish Squadron’ on the cover of the book about 303 Squadron published in August 1942.

The text of the book can be read here:

http://www.archive.org/details/squadron303006829mbpThe language in the translation is even more "flowery" than in the original, but the stories and stats are very interesting, especially seeing how this was the highest scoring squadron with the highest scoring aces of the battle on the British side. Thanks to Woke_Up_Dead for the link.

WAAF mechanics helping the pilot strap into a Spitfire Mk II of 411 (Canadian) Squadron, at Digby in Lincolnshire in 1941.