Posted By: RedToo

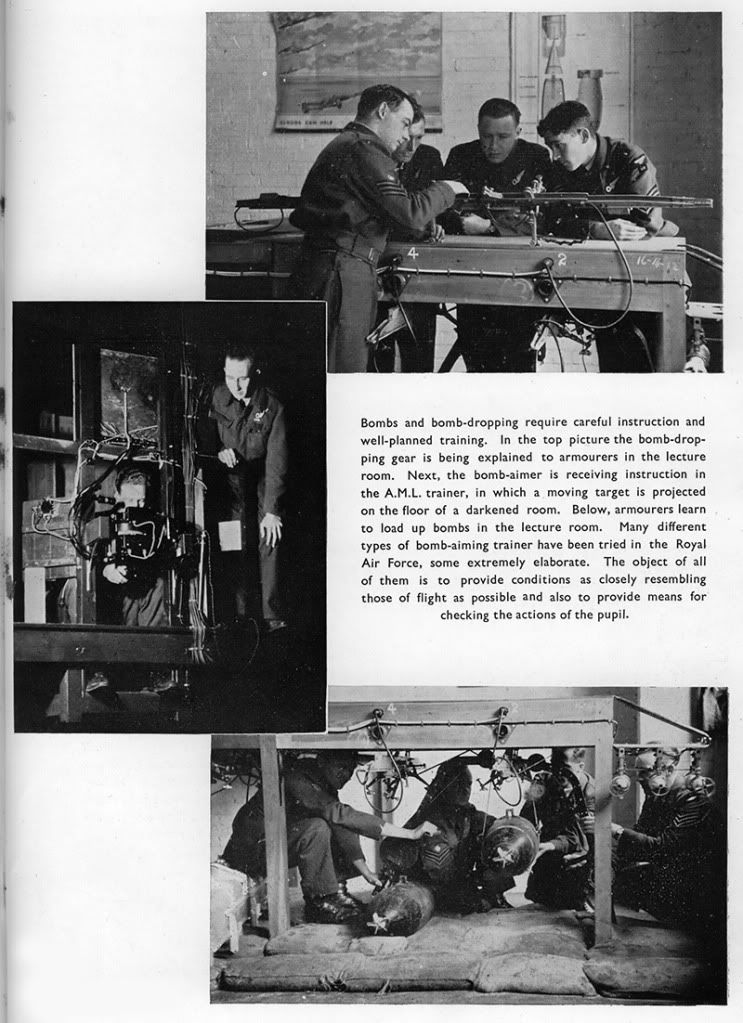

While we're waiting for CloDo. Final instalment and end of thread. 14 5 2011. - 02/28/09 06:49 PM

Hi all,

I've just acquired this book: Winged Words, published in 1941. It contains the verbatim transcripts of some of 150 broadcasts made by RAF officers, airmen and the WAAF for the BBC. They make fascinating reading, complete with misconceptions of the time. Some of them mention operations and personnel familiar to us, others are long forgotten. I thought posting them here might make the wait for BoB SoW seem a little shorter. The first is from December 1939, the last February 1941. I'll try to post one a week. Without further ado here is the first.

RedToo.

December, 1939

CHRISTMAS DAY IN COASTAL COMMAND

BY A SQUADRON LEADER, R.A.F.V.R.

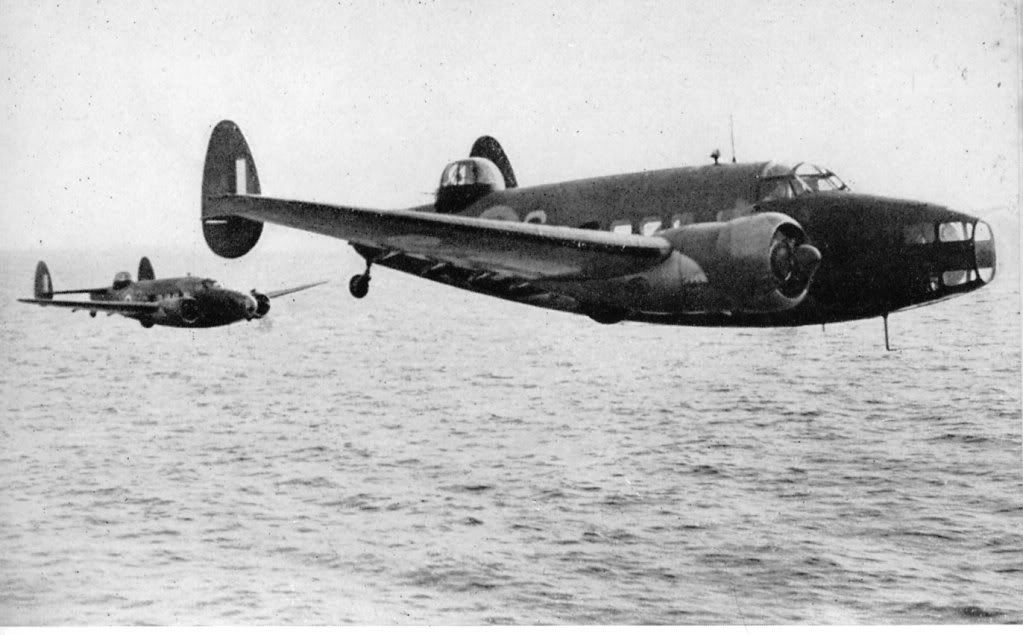

As you can imagine, the Royal Air Force in Great Britain has had to be on its toes over Christmas. This has been particularly true of the crews of Coastal Command aircraft.

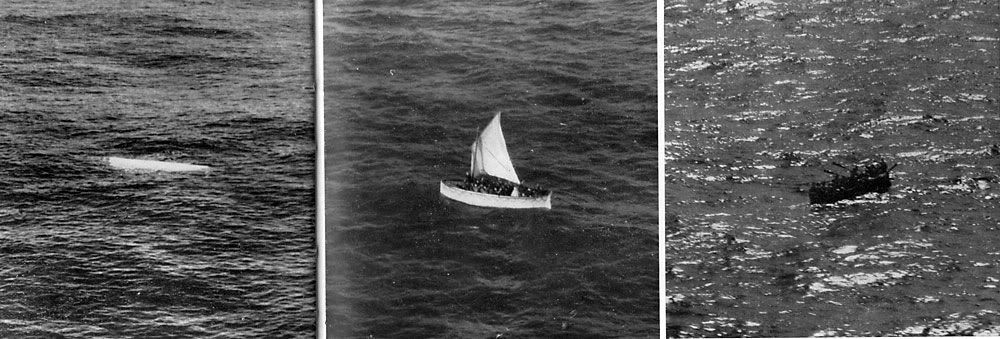

Co-operating with the Royal Navy, they are responsible for the safety of shipping on the seas of Western Europe. For them, there could be no holiday . . . Enemy submarines for ever on the prowl . . . the possibility of German warships breaking out from their bases . . . watch to be kept on the great convoys of merchant vessels on their way to Britain . . . the traffic lanes to be searched for mines.

Since the war began, the aircraft of the Coastal Command have flown fully four million miles, on watch and guard over the North Sea and the Atlantic. In other words, in four months, the crews of this Command have covered a distance equal to more than 165 journeys round the Equator.

A substantial part of this immense air mileage has been contributed by the Royal Air Force flying boats, many of which are flying boats of the type used on the Empire routes for the carriage of passengers and mails.

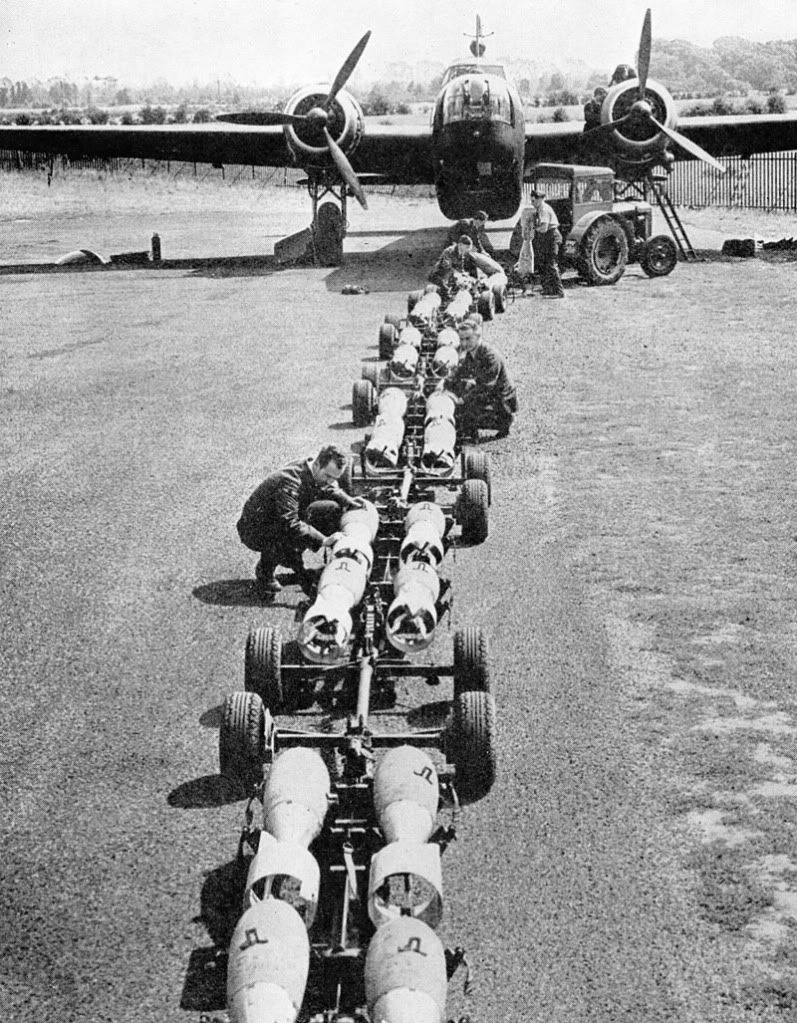

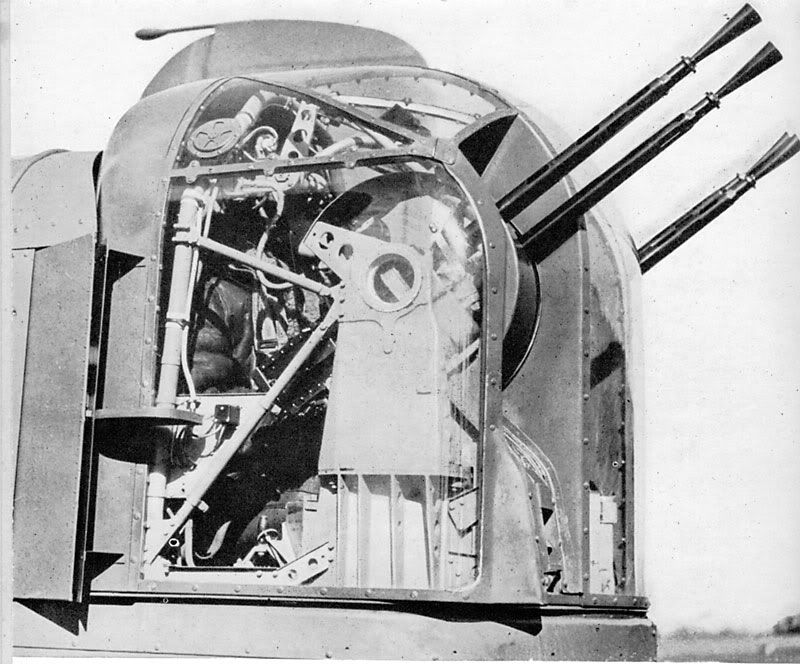

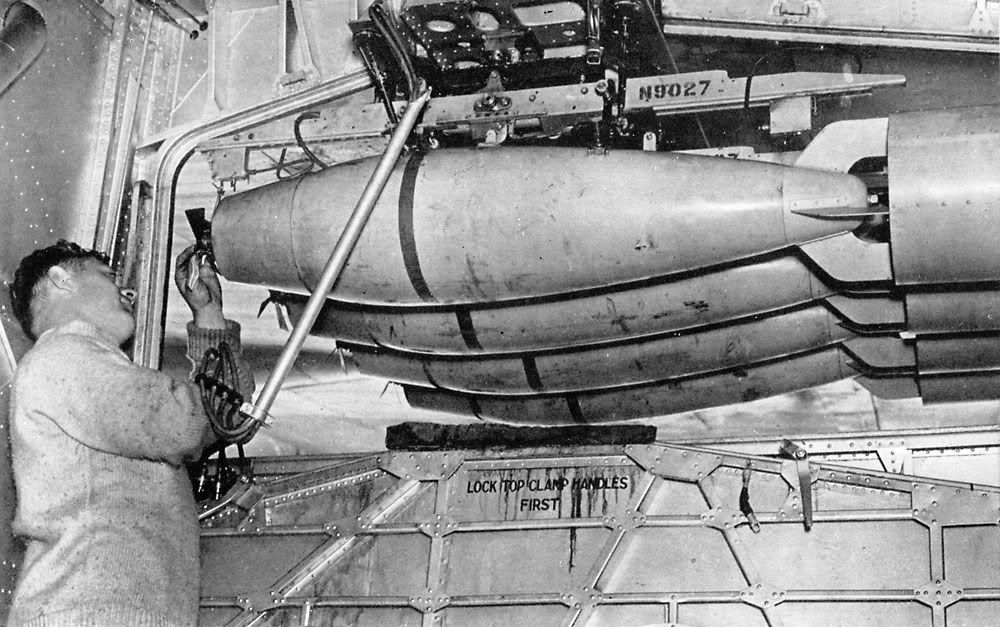

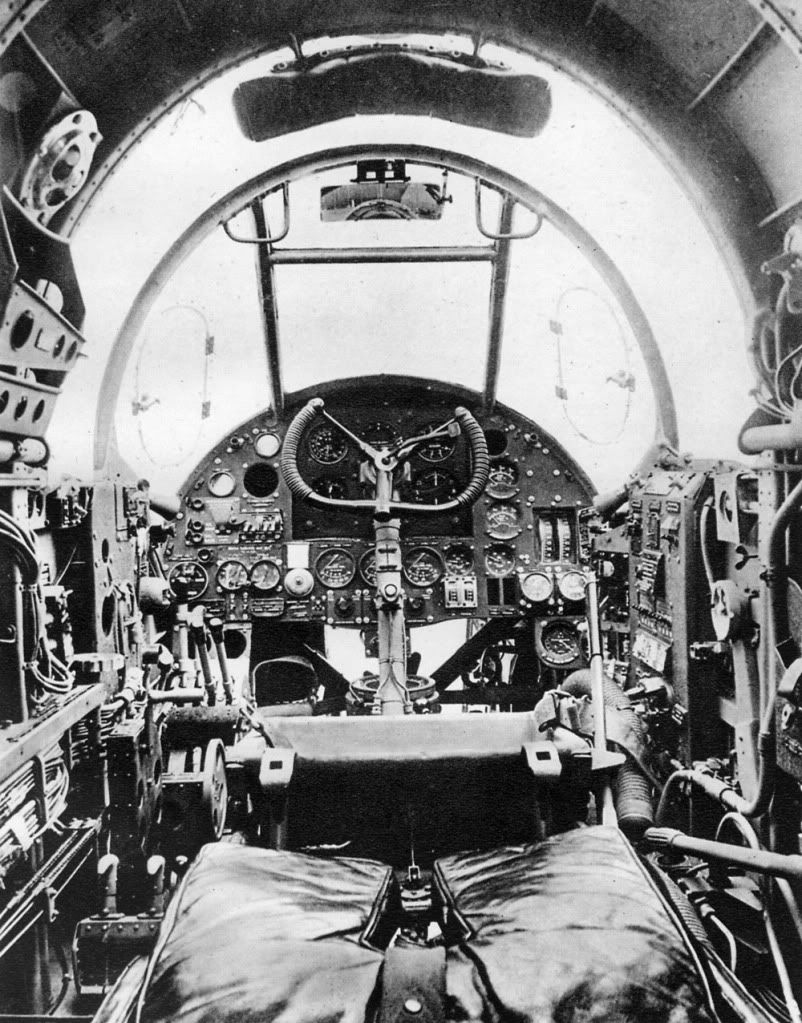

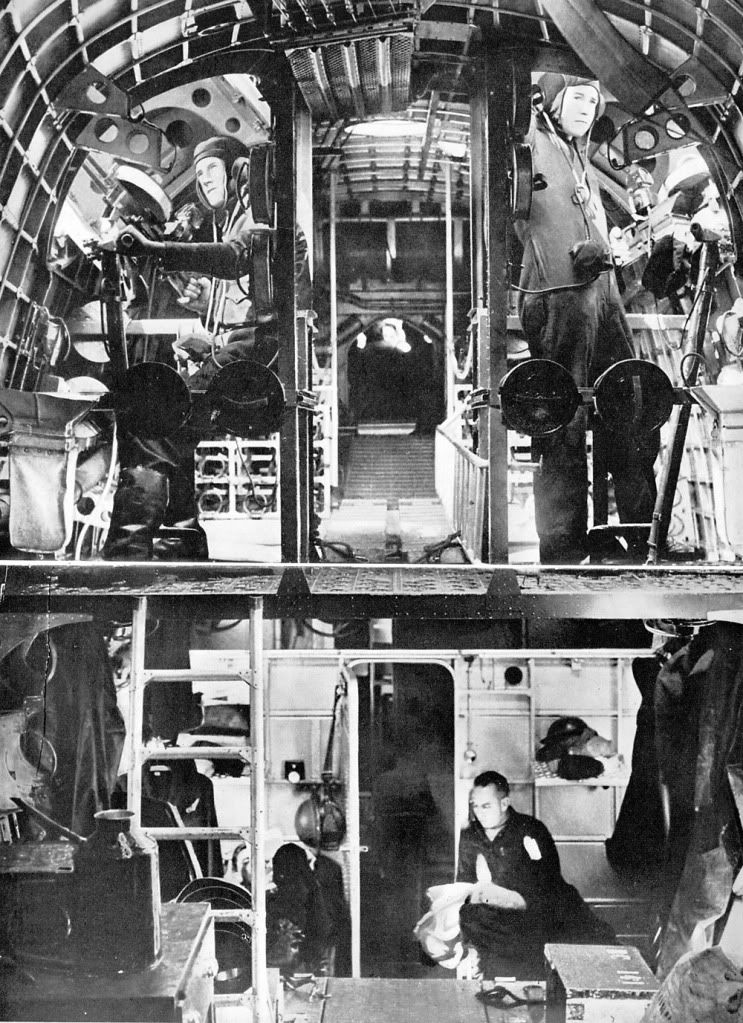

In outward appearance these Royal Air Force and Empire flying boats are identical. But the interior furnishings are very different. In one, as you know, there are armchair seats, tasteful dining-rooms, and comfortable sleeping quarters. But the inside of an R.A.F. flying boat is an arsenal, with batteries of guns on both decks and a ton of bombs slung from a kind of overhead railway on the roof, ready to be run out for easy dropping from the wings.

I spent Christmas Day in one of these flying boats on an anti-submarine and convoy protection patrol of upwards of 1,500 miles over the Atlantic. The crews of the aircraft were aboard, as usual, before dawn, and took off in the darkness so that advantage might be taken of every minute of daylight at sea.

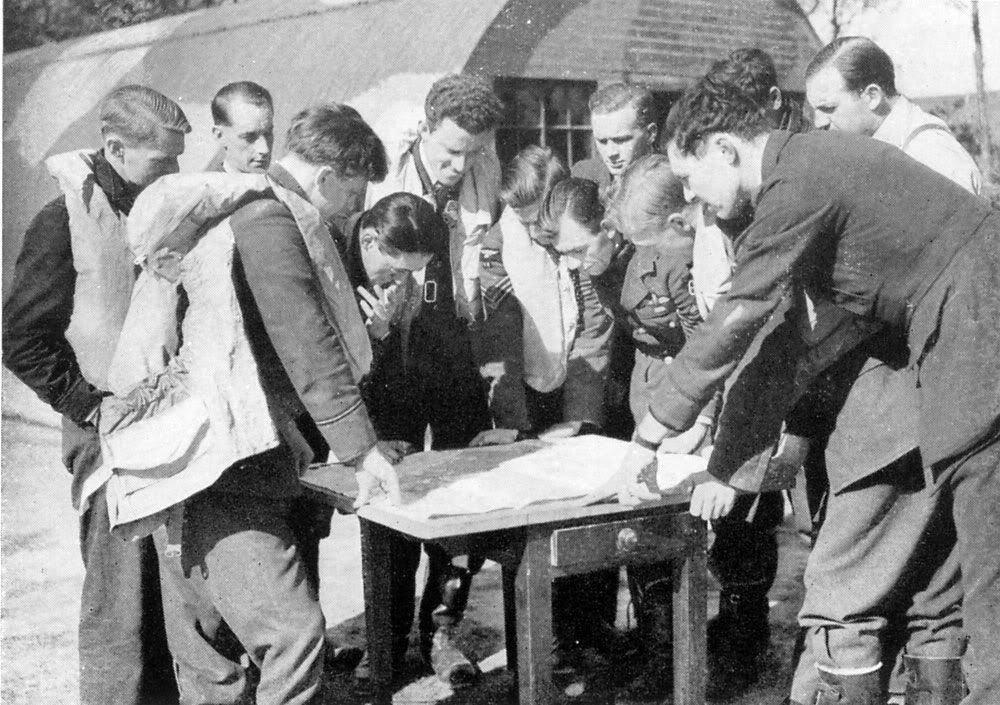

Before we boarded the flying boat, pilots and navigators received their instructions for their Christmas Day's work in a small hut which is the Operations Room of the Squadron. Orders were read to them in front of a big map of the Atlantic seaboard on which seven white graveyard crosses are pinned. Each cross marks the spot where a German submarine has been destroyed by a flying boat of this single squadron.

Just before we left to embark, an orderly from the wireless station brought in a sheaf of messages. They were Christmas greetings from the pilots, crews and passengers on Empire flying boats which are still maintaining, just as in peacetime, their twice weekly, two-way services between Britain and Australia, Central Africa, and South Africa. These messages of goodwill to the Royal Air Force flying boats bad been sent from their sister flying boats while they were in the air over the Dutch East Indies, Singapore, Malay, Thailand, Burma, India, the Sudan, Egypt, Kenya and Uganda.

Reading them in that tiny hut on the English shore of the Atlantic on Christmas morning, one could not help feeling some pride in the fact that the British Empire's Command of its civil flying routes is still completely unchallenged.

There was another Christmas Day message. It came from the Australian crews of flying boats now working with the Royal Air Force from a station further north on the west coast of Britain.

By dawn, which came in saffron splendour, we were having breakfast nearly 200 miles at sea. A FULL breakfast�grapefruit, bacon, sausages, eggs, coffee and toast, served piping hot from the galley next door. The cook reported to the young captain of the flying boat, a youth of twenty-two, that he wasn't satisfied with the behaviour of the ice-box in the galley. Why he should be worrying about an ice-box 2,000 feet over the Atlantic on a freezing Christmas morning, neither the pilot nor I could understand.

Back in the control cabin which, like the gun turrets, was decorated with holly and mistletoe, we saw the answer to Germany's propaganda claim that the Nazi sea and air fleets are blockading Britain.

In the first flush of day, scores of heavy-laden merchant ships from Australia, New Zealand, Africa and South America were riding the seas triumphantly to Britain. Every mile or two for the rest of the day we came on more ships going on their business, unaccompanied and unafraid.

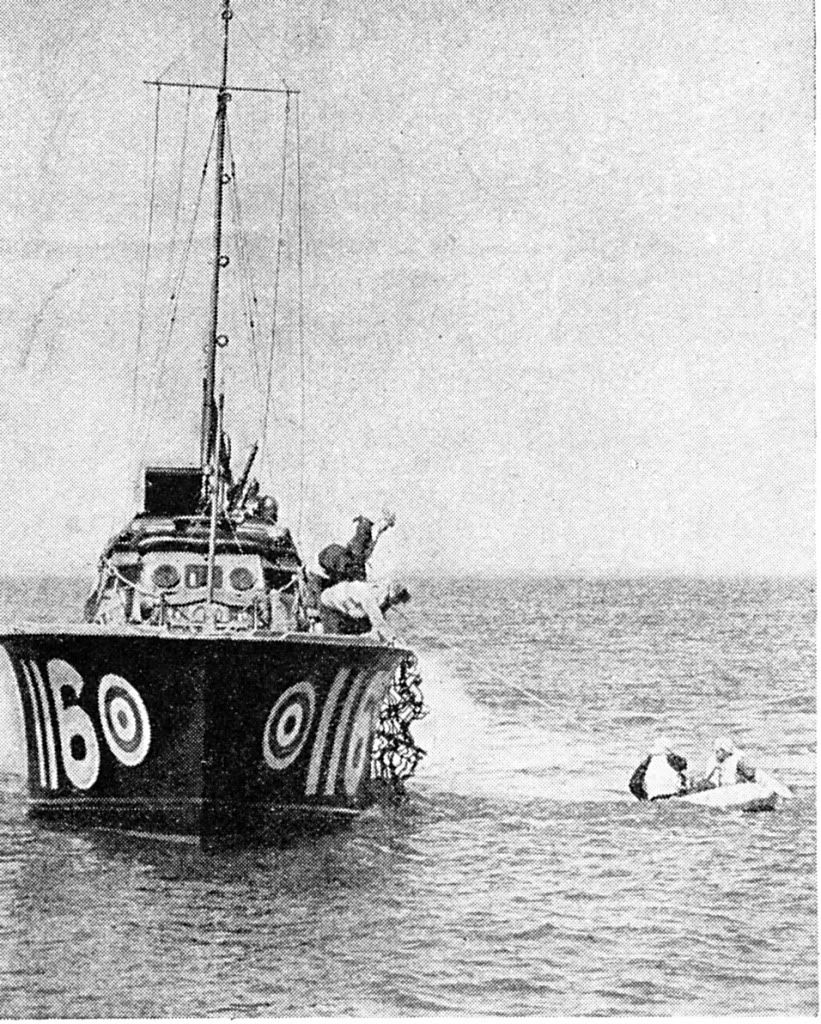

But our special job for Christmas Day was to find and protect a convoy which had been assembled at a rendezvous from all parts of the world and which an escort of French warships was bringing along. We knew that the convoy was about twenty hours late, and that it had gone far off the course set for it because of bad weather and threatened submarine attack.

We could only guess the course it was taking. The ships themselves couldn't help us to locate them. They had, of course, to keep wireless silence so that their position might not be betrayed to lurking U-boats.

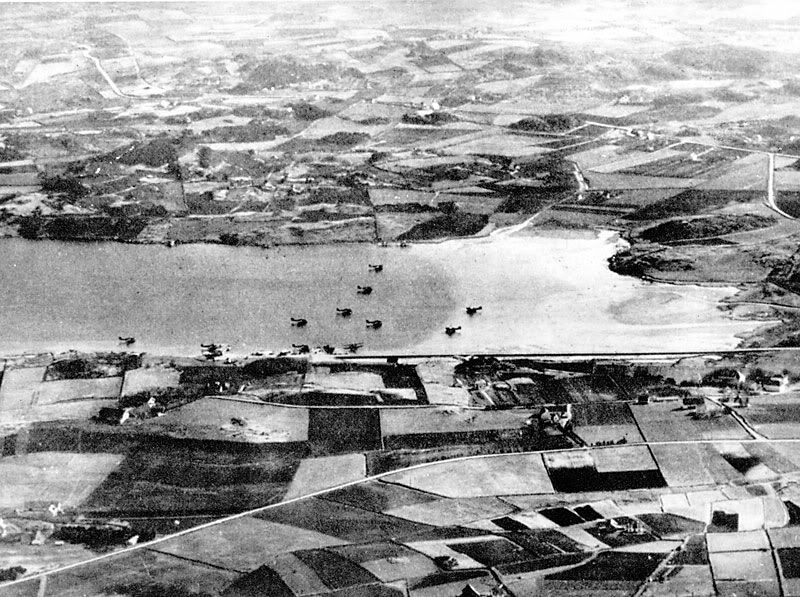

Our flying boat combed the sea for 5 50 miles. Then we found the convoy. Rather, it nearly found us! Cloud had become so dense and low that often we could see only the nose of the flying boat and the wing-tip floats. I heard the pilot beside me whistle sharply. "Blimey!" he said as he lifted the boat suddenly from the height of sixty feet at which we had been flying. In the nick of time he had avoided the masthead of a ship which had appeared beneath the wing. As he climbed to starboard, we saw another mast . . . then another . . . then mast after mast. His anxious look gave way to a happy smile. He took his hand from the joy�stick and cocked his thumb. He was over the lost convoy.

Through the thick mist we could see the columns of ships flashing Christmas greetings to us with their lamps.

The bank of low cloud which blanketed the sea was now more than 200 miles square. We flew through it for a couple of hours and then located the British destroyers which were waiting to take over from the French warships. By lamp signals we gave them the position and course of the convoy.

Our Christmas Day job was now half done.

We had to fly back to the convoy, and for the remaining five hours of daylight, sweep the sea ahead of it for enemy submarines.

As quickly as it had fallen, the thick belt of mist vanished. Wintry sunshine filtered into the flying boat as the crew sat down, two at a time, to a quick Christmas dinner of soup, goose and plum-pudding. Until dusk we cruised for 500 miles in the path which the convoy would take to England. There were no submarines about. At least, if there were, they kept their heads down for fear of our bombs. And a U-boat submerged at sea is as useless as it would be in its base in Germany. Part of the job of the Coastal Command of the Royal Air Force is to destroy them or, failing that, to keep them submerged.

Twice the look-out men on our flying boat gave the "action" call to bring the crew to submarine stations. They did so by pressing a button which caused an electric hooter to scream "DAH-DE-DIH-DI-DOH" throughout the boat. Both times a sea marker was thrown overboard by the lookout men, and the pilot made the flying boat stand on its wing-tip so that the sea was like a wall in front of us, with the horizon over our heads. The pilot's fingers caressed the bomb switches. But no bombs fell. As he swept round the column of smoke rising from the sea-markers, he decided that the ripples of water among the "white-horses" which the look-out men had seen were not the footprints of a submarine periscope, but only the foam on the trail of drifting wreckage.

We had left the English coast in the morning black-out against air raids. Twelve hours later we came back to it�again in complete darkness, just in time for a second, and more leisurely, Christmas dinner.

To-day, Boxing day, the flying boat is out again over the Atlantic, guarding the great convoy of merchant ships on another day's safe march to England. Its crew and the crews of the other flying boats of the Squadron have asked me to offer you their good wishes.

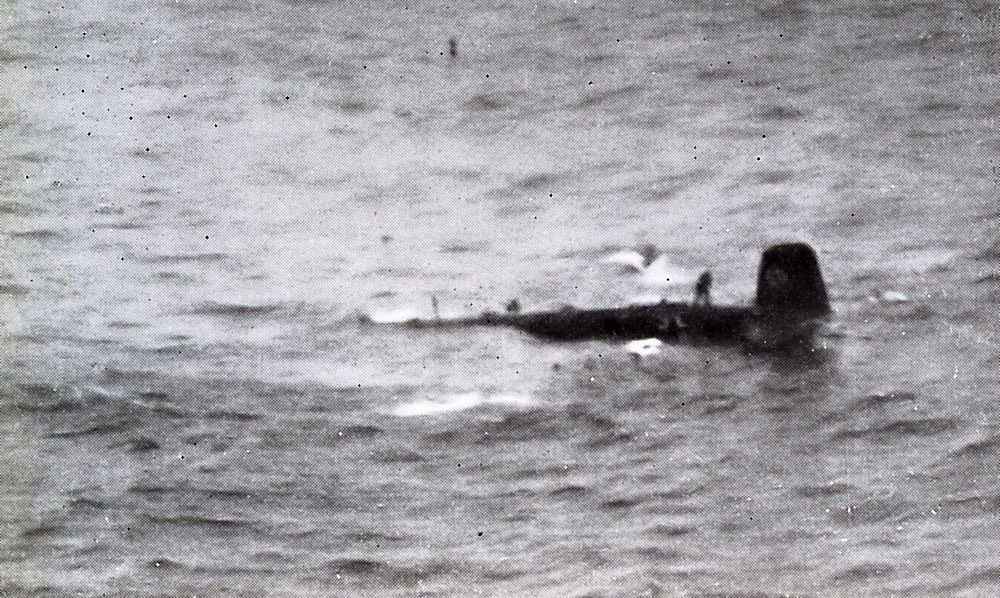

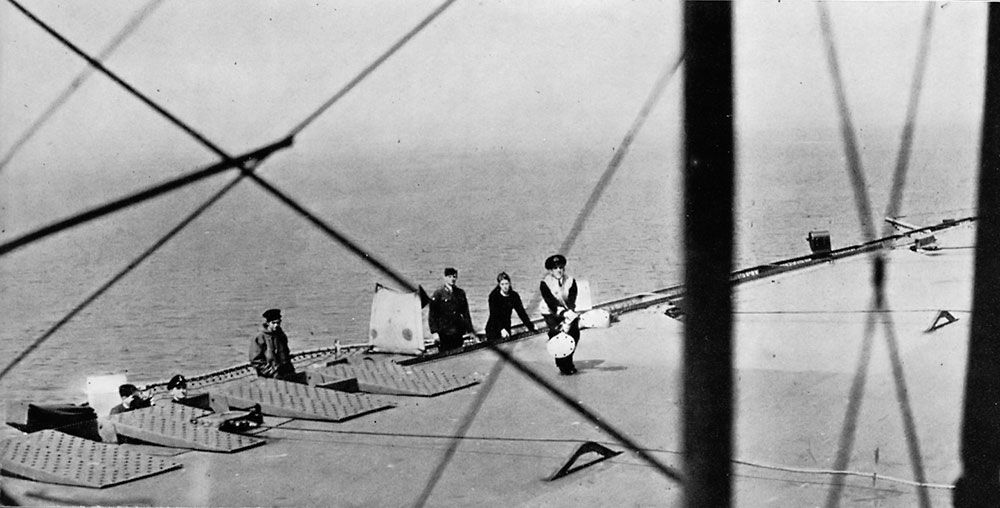

![[Linked Image]](http://img.photobucket.com/albums/v369/RedToo/Sunderland.jpg)

A Sunderland taking off.

I've just acquired this book: Winged Words, published in 1941. It contains the verbatim transcripts of some of 150 broadcasts made by RAF officers, airmen and the WAAF for the BBC. They make fascinating reading, complete with misconceptions of the time. Some of them mention operations and personnel familiar to us, others are long forgotten. I thought posting them here might make the wait for BoB SoW seem a little shorter. The first is from December 1939, the last February 1941. I'll try to post one a week. Without further ado here is the first.

RedToo.

December, 1939

CHRISTMAS DAY IN COASTAL COMMAND

BY A SQUADRON LEADER, R.A.F.V.R.

As you can imagine, the Royal Air Force in Great Britain has had to be on its toes over Christmas. This has been particularly true of the crews of Coastal Command aircraft.

Co-operating with the Royal Navy, they are responsible for the safety of shipping on the seas of Western Europe. For them, there could be no holiday . . . Enemy submarines for ever on the prowl . . . the possibility of German warships breaking out from their bases . . . watch to be kept on the great convoys of merchant vessels on their way to Britain . . . the traffic lanes to be searched for mines.

Since the war began, the aircraft of the Coastal Command have flown fully four million miles, on watch and guard over the North Sea and the Atlantic. In other words, in four months, the crews of this Command have covered a distance equal to more than 165 journeys round the Equator.

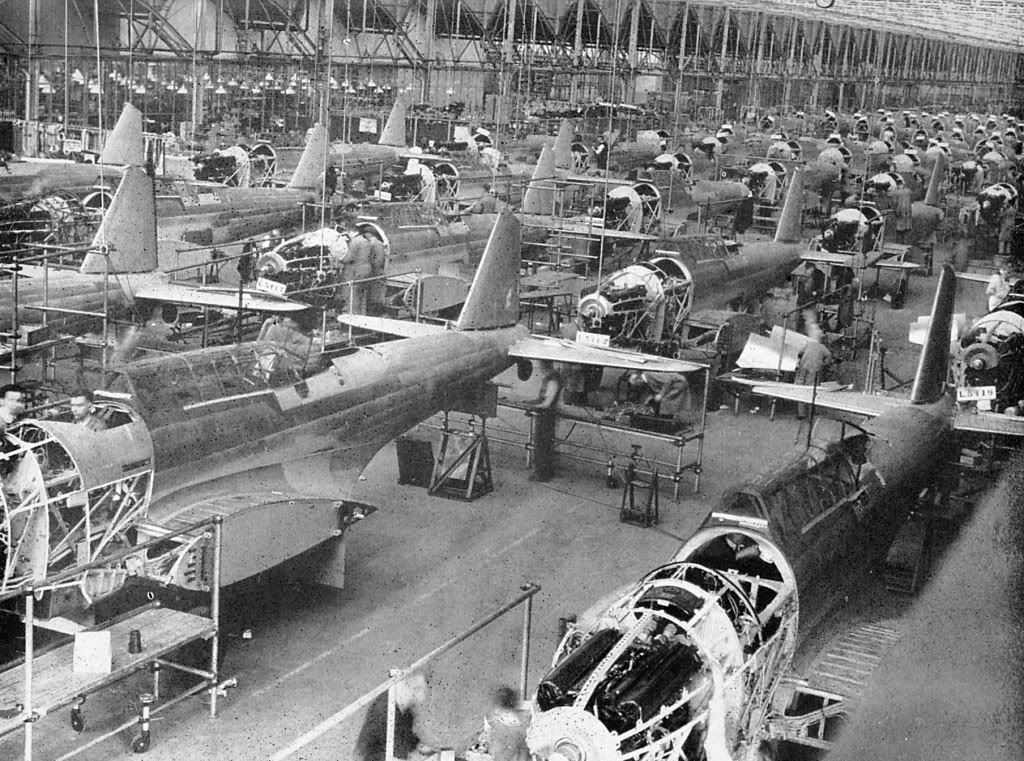

A substantial part of this immense air mileage has been contributed by the Royal Air Force flying boats, many of which are flying boats of the type used on the Empire routes for the carriage of passengers and mails.

In outward appearance these Royal Air Force and Empire flying boats are identical. But the interior furnishings are very different. In one, as you know, there are armchair seats, tasteful dining-rooms, and comfortable sleeping quarters. But the inside of an R.A.F. flying boat is an arsenal, with batteries of guns on both decks and a ton of bombs slung from a kind of overhead railway on the roof, ready to be run out for easy dropping from the wings.

I spent Christmas Day in one of these flying boats on an anti-submarine and convoy protection patrol of upwards of 1,500 miles over the Atlantic. The crews of the aircraft were aboard, as usual, before dawn, and took off in the darkness so that advantage might be taken of every minute of daylight at sea.

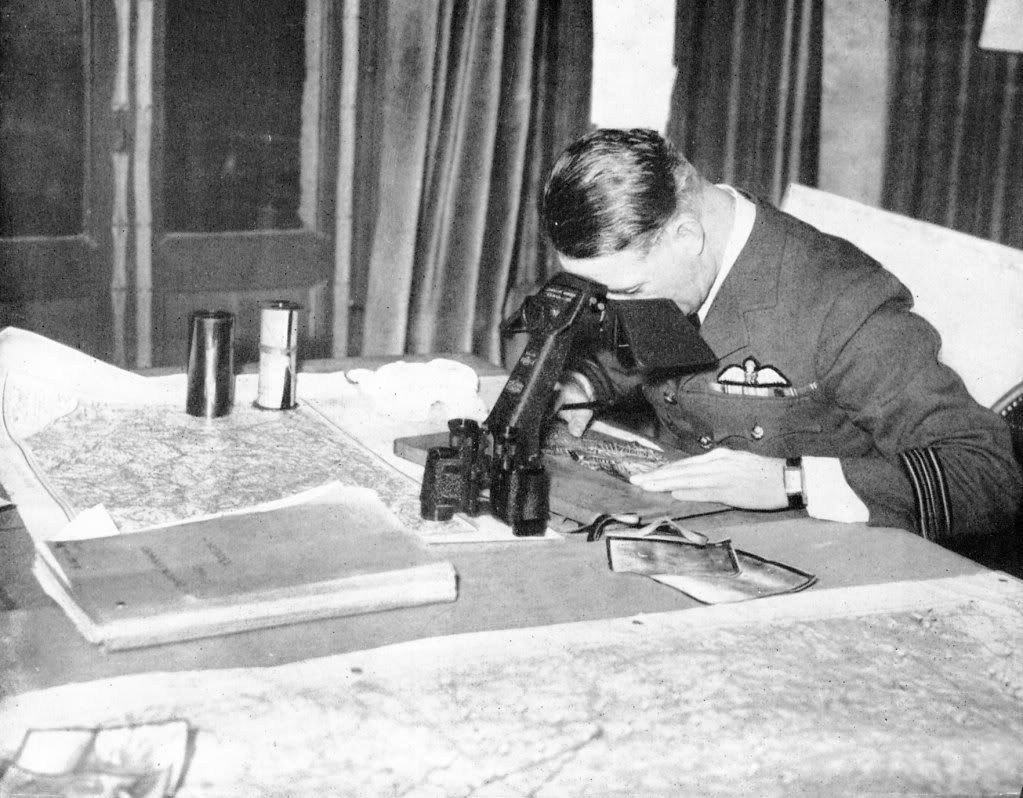

Before we boarded the flying boat, pilots and navigators received their instructions for their Christmas Day's work in a small hut which is the Operations Room of the Squadron. Orders were read to them in front of a big map of the Atlantic seaboard on which seven white graveyard crosses are pinned. Each cross marks the spot where a German submarine has been destroyed by a flying boat of this single squadron.

Just before we left to embark, an orderly from the wireless station brought in a sheaf of messages. They were Christmas greetings from the pilots, crews and passengers on Empire flying boats which are still maintaining, just as in peacetime, their twice weekly, two-way services between Britain and Australia, Central Africa, and South Africa. These messages of goodwill to the Royal Air Force flying boats bad been sent from their sister flying boats while they were in the air over the Dutch East Indies, Singapore, Malay, Thailand, Burma, India, the Sudan, Egypt, Kenya and Uganda.

Reading them in that tiny hut on the English shore of the Atlantic on Christmas morning, one could not help feeling some pride in the fact that the British Empire's Command of its civil flying routes is still completely unchallenged.

There was another Christmas Day message. It came from the Australian crews of flying boats now working with the Royal Air Force from a station further north on the west coast of Britain.

By dawn, which came in saffron splendour, we were having breakfast nearly 200 miles at sea. A FULL breakfast�grapefruit, bacon, sausages, eggs, coffee and toast, served piping hot from the galley next door. The cook reported to the young captain of the flying boat, a youth of twenty-two, that he wasn't satisfied with the behaviour of the ice-box in the galley. Why he should be worrying about an ice-box 2,000 feet over the Atlantic on a freezing Christmas morning, neither the pilot nor I could understand.

Back in the control cabin which, like the gun turrets, was decorated with holly and mistletoe, we saw the answer to Germany's propaganda claim that the Nazi sea and air fleets are blockading Britain.

In the first flush of day, scores of heavy-laden merchant ships from Australia, New Zealand, Africa and South America were riding the seas triumphantly to Britain. Every mile or two for the rest of the day we came on more ships going on their business, unaccompanied and unafraid.

But our special job for Christmas Day was to find and protect a convoy which had been assembled at a rendezvous from all parts of the world and which an escort of French warships was bringing along. We knew that the convoy was about twenty hours late, and that it had gone far off the course set for it because of bad weather and threatened submarine attack.

We could only guess the course it was taking. The ships themselves couldn't help us to locate them. They had, of course, to keep wireless silence so that their position might not be betrayed to lurking U-boats.

Our flying boat combed the sea for 5 50 miles. Then we found the convoy. Rather, it nearly found us! Cloud had become so dense and low that often we could see only the nose of the flying boat and the wing-tip floats. I heard the pilot beside me whistle sharply. "Blimey!" he said as he lifted the boat suddenly from the height of sixty feet at which we had been flying. In the nick of time he had avoided the masthead of a ship which had appeared beneath the wing. As he climbed to starboard, we saw another mast . . . then another . . . then mast after mast. His anxious look gave way to a happy smile. He took his hand from the joy�stick and cocked his thumb. He was over the lost convoy.

Through the thick mist we could see the columns of ships flashing Christmas greetings to us with their lamps.

The bank of low cloud which blanketed the sea was now more than 200 miles square. We flew through it for a couple of hours and then located the British destroyers which were waiting to take over from the French warships. By lamp signals we gave them the position and course of the convoy.

Our Christmas Day job was now half done.

We had to fly back to the convoy, and for the remaining five hours of daylight, sweep the sea ahead of it for enemy submarines.

As quickly as it had fallen, the thick belt of mist vanished. Wintry sunshine filtered into the flying boat as the crew sat down, two at a time, to a quick Christmas dinner of soup, goose and plum-pudding. Until dusk we cruised for 500 miles in the path which the convoy would take to England. There were no submarines about. At least, if there were, they kept their heads down for fear of our bombs. And a U-boat submerged at sea is as useless as it would be in its base in Germany. Part of the job of the Coastal Command of the Royal Air Force is to destroy them or, failing that, to keep them submerged.

Twice the look-out men on our flying boat gave the "action" call to bring the crew to submarine stations. They did so by pressing a button which caused an electric hooter to scream "DAH-DE-DIH-DI-DOH" throughout the boat. Both times a sea marker was thrown overboard by the lookout men, and the pilot made the flying boat stand on its wing-tip so that the sea was like a wall in front of us, with the horizon over our heads. The pilot's fingers caressed the bomb switches. But no bombs fell. As he swept round the column of smoke rising from the sea-markers, he decided that the ripples of water among the "white-horses" which the look-out men had seen were not the footprints of a submarine periscope, but only the foam on the trail of drifting wreckage.

We had left the English coast in the morning black-out against air raids. Twelve hours later we came back to it�again in complete darkness, just in time for a second, and more leisurely, Christmas dinner.

To-day, Boxing day, the flying boat is out again over the Atlantic, guarding the great convoy of merchant ships on another day's safe march to England. Its crew and the crews of the other flying boats of the Squadron have asked me to offer you their good wishes.

![[Linked Image]](http://img.photobucket.com/albums/v369/RedToo/Sunderland.jpg)

A Sunderland taking off.

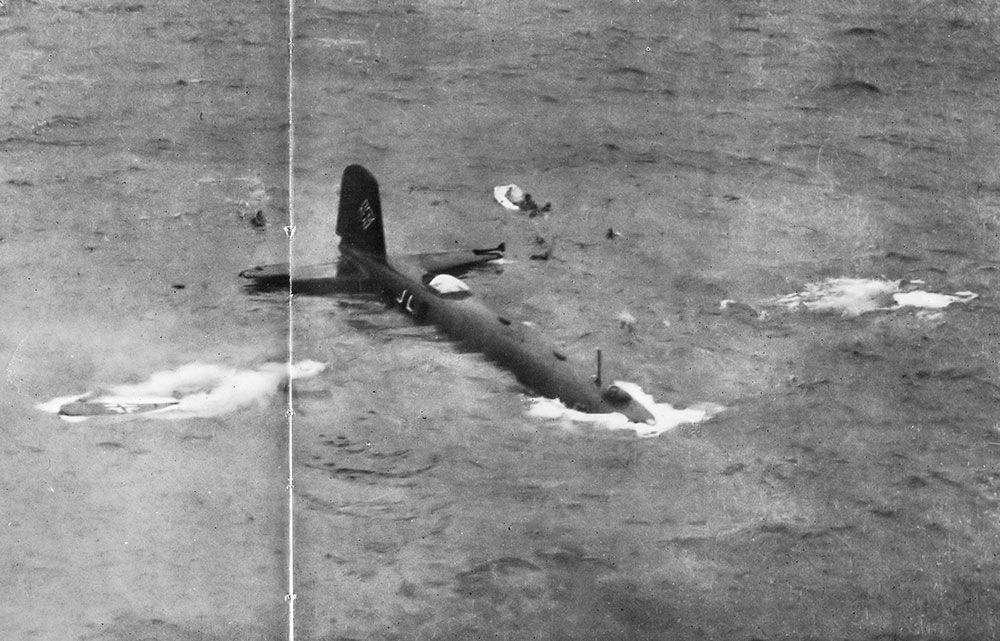

![[Linked Image]](http://img.photobucket.com/albums/v369/RedToo/HMSAudacity1.jpg)

![[Linked Image]](http://img.photobucket.com/albums/v369/RedToo/HMSAudacity2.jpg)