|

#3191880 - 01/28/11 10:07 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

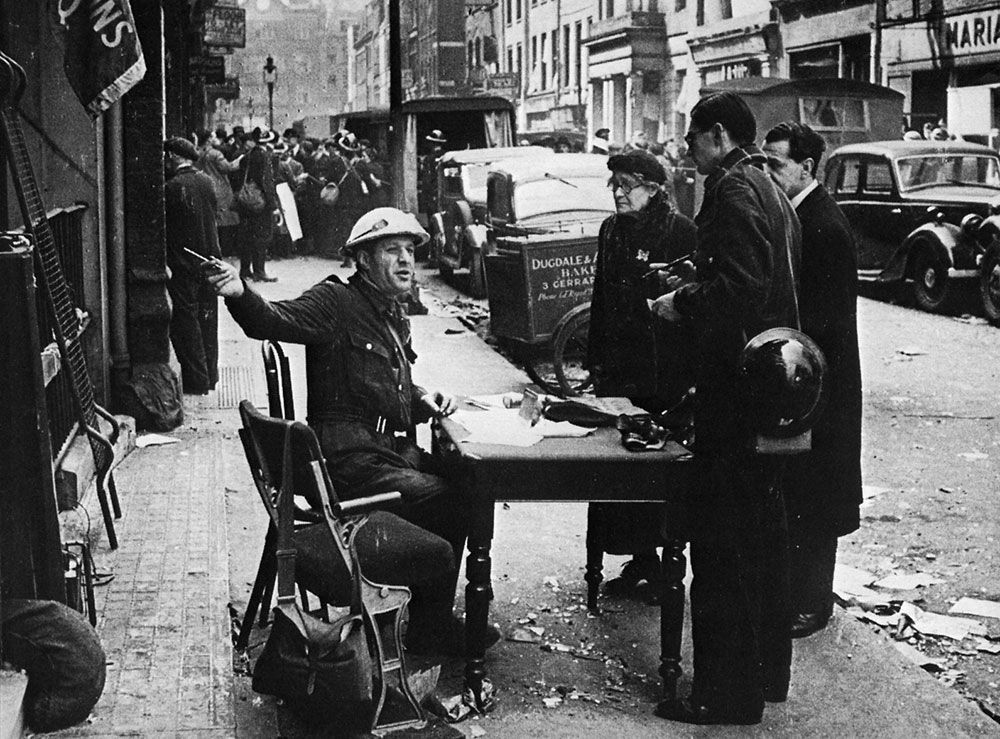

Part 98. From ‘Raiders Overhead a Diary of the London Blitz’ By ARP Warden Barbara Nixon published in 1943. Excerpt from Chapter 3 ‘First Blood’. My first incident occurred one afternoon in the second week. A soldier, however highly trained, will yet be apprehensive about his own reactions when, for the first time, he actually comes under fire. I had been fairly confident that I could behave reasonably well under gunfire and bombing, and the first seven nights had, more or less, justified my confidence. But what I was very unsure of was what my reactions to casualties would be. I had never seen a dead body, I was even squeamish about handling dead animals, and I was terrified that I might be sick when I saw my first entrails, just as some people cannot stop themselves fainting at the sight of blood. At later incidents one forgot oneself entirely in the job on hand. But on this occasion, because I was unsure of myself, I was acutely self-conscious, and, as a protection, adopted as detached an attitude as I could. I had to watch myself, as well as the objective situation. It was a grey, damp afternoon in late September, ten days after the start of the air-blitz on London. I was bicycling along a shabby street in a district some miles from my own. The day alerts were so frequent that it was difficult to remember whether the last wailing of the siren had been the alert or the ‘all clear.’ It was a street of narrow houses, so decrepit that they might well have crumbled to pieces had they not been held up by occasional large office buildings, and even these were dingy and decayed. Dirty shop windows announced that they were high-class laundries, or would mend your boots while you waited, or would buy cast-off clothing. The whole derelict street and the lanes leading into it were calling for the house-breaker. A little further on, however, in a side turning on the right, the LCC had made a start, and a block of balconied workers' flats had been erected. They were well designed, and the plaster facings and the brickwork were still unsooted by London's grime. Suddenly, before I heard a sound, the shabby, ill-lit, five-storey building ahead of me swelled out like a child's balloon, or like a Walt Disney house having hiccups. I looked at it in astonishment, that bricks and mortar could stretch like rubber. At the point when it must burst, the glass fell out. It did not hurtle, it simply cracked and dropped out, allowing the straining building to deflate and return to normal. Almost instantaneously there was a crash and a double explosion in the street to my right. As the blast of air reached me I left my saddle and sailed through the air, heading for the area railings. The tin hat on my shoulder took the impact, and as I stood up I was mildly surprised to find that I was not hurt in the least. The corner buildings had diverted the full force of blast; indeed, to judge by the number of idiotic thoughts that raced through my head, my progress to the railings might almost have been in 'slow motion.' I had not heard any whistle of the bombs coming down, only the explosion, and now the sound of an aeroplane's engine starting up. I thought, 'So it's true—you don't hear the one that gets, or nearly gets, you.' For no reason except that one handbook had said so, I blew my whistle. An old lady appeared in her doorway and asked, 'What was all that?' I told her it was a bomb, but she was stone-deaf and I had to abandon bawling for pantomime of a bomb exploding before she would agree to go into a surface shelter. After putting a dressing on some small cuts on a man's face, I turned back towards the site of the damage. I did not know the locality, but, again, the handbook said that when an alert sounded, a warden away from his home area should report to the nearest Post. The damage was thirty yards away, but the corner building, which had diverted some of the blast from me, was still standing. At four in the afternoon there would certainly be casualties. Now I would know whether I was going to be of any use as a warden or not, and I wanted to postpone the knowledge. I dared not run. I had to go warily, as if I were crossing a minefield with only a rough sketch of the position of the mines—only the danger-spots were in myself. I was not let down lightly. In the middle of the street lay the remains of a baby. It had been blown clean through the window, and had burst on striking the roadway. To my intense relief, pitiful and horrible as it was, I was not nauseated, and found a torn piece of curtain in which to wrap it. Two HE bombs had fallen on the new flats, and a third on an equally new garage opposite. In all this grimy derelict area, they had struck the only decent habitations. The CD services arrived quickly. There was a large number of 'white hats,' but as far as one could see no one person took charge, and there were no blue incident flags. I offered my services, and was thanked but given nothing to do, so busied myself finding blankets to cover the five or six mutilated bodies in the street. A small boy, aged about 13, had one leg torn off and was still conscious, though he gave no sign of any pain. In the garage a man was pinned under a capsized Thorneycroft lorry, and most of the side wall and roof were piled on top of that. The Heavy Rescue Squad brought ropes, and heaved and tugged at the immense lorry. They got the man out, unconscious, but alive. He looked like a terra-cotta statue, his face, his teeth, his hair, were all a uniform brick colour. Eleven had been killed but a larger number were badly injured— an old man staggered down supported by two girls holding a towel to his face; as we laid him on a stretcher the towel dropped, and his face was shockingly cut away by glass. It was astonishing that he had been able to walk down stairs. Three more stretcher cars and two ambulances arrived, but they had to park some distance away because of the debris. If they had been directed to approach from the western side they could have driven much closer. The wardens began to check up the flats. As I did not know the residents, or how many of them there ought to be, I could not help, and stayed below. But by now the news had travelled, and women back from shopping, girls, and a few men from local factories, came running and scrambling over the debris in the street. 'Where is Julie?' 'Is my Mum- all right?' I was besieged, but I could not help them. They shouted the names of their relatives and scanned the faces of the dusty, dishevelled survivors. Those who found that they had lost a relation seemed numbed by the shock and were quiet, whereas a woman who found her family intact promptly had hysterics. The sudden relief from an awful fear was more unnerving at the moment than the confirmation of the fear. A little later I left: there was nothing apparently that I could do, little enough that I had done. Any bystander could have been as helpful as I had been, and I felt discouraged and depressed. My bicycle was bent, but since the wheels would still go round, I clanked and wobbled on it back to my own Post. Tommy Brickman was there, and greeted me with 'Blimey, your face!' I explained how it had got so dirty, and noticed, to my amusement, that he was obviously chagrined that it had been I, and not himself, who had 'had the fun.' Tommy was an energetic and conscientious warden, but both imaginative and loquacious. His existence was a continuous conversation piece with no back answers allowed. At the same time, he was quite incapable of seeing only six German planes, or being missed by only a 50-kg. bomb, or of extinguishing only a dozen incendiaries; it had always to be 60 planes, a 1,000-kg. bomb, or hundreds of incendiaries at least. If Tommy went away for a day or so to another town, we knew that that town would have 'the biggest blitz ever.' If he travelled by train, that train was machine-gunned. It was a habit that irritated the more serious-minded members of the Post, though I could not myself see that it mattered whether Tommy's graphic and hair-raising accounts were in fact true or not. I think he found me a pleasant audience, as I always egged him on by asking innocent questions. However, this time it was my story. Tommy made me some tea, but before we had time to drink it, the evening siren went, and I left for my sector post. It was another all-night session and the 'all clear' did not sound until 6.15 a.m. We were supposed to wait, however, until we received the 'white' on the telephone, and I waited irritably for half an hour, angry with Control for being so inconsiderate of us after a twelve-hour raid. But when the man who lived in the flat above our post came down, he pointed out that Jim Mackin, the Post Warden, had come round at midnight to tell me that the phone was out of order. To my alarm, I found that I could not remember that, or anything else after reporting for duty at 6.30 p.m. I replied, 'Oh yes, of course,' but as I walked home I tried to reconstruct the evening. I remembered the incident in the afternoon, but the twelve hours after that were a complete blank; I could not even remember whether I had gone home for supper. I counted the plates in the kitchen, but that did not tell me anything, and I was really frightened as I waited for someone in the house to get up. For all I knew I might have made an awful fool of myself. Apparently, I had behaved quite normally, made my usual tour of the shelters, had supper, and helped someone to change the wheel of his car, but I still could not remember any of it. I had one hazy picture of a white hat in a doorway, which must have been Jim Mackin, but that was all. If I was to have that sort of reaction after every incident, it was going to be inconvenient.  The ARP post open for business in the street.  Finsbury ARP post number 2 1941.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3198721 - 02/04/11 08:15 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

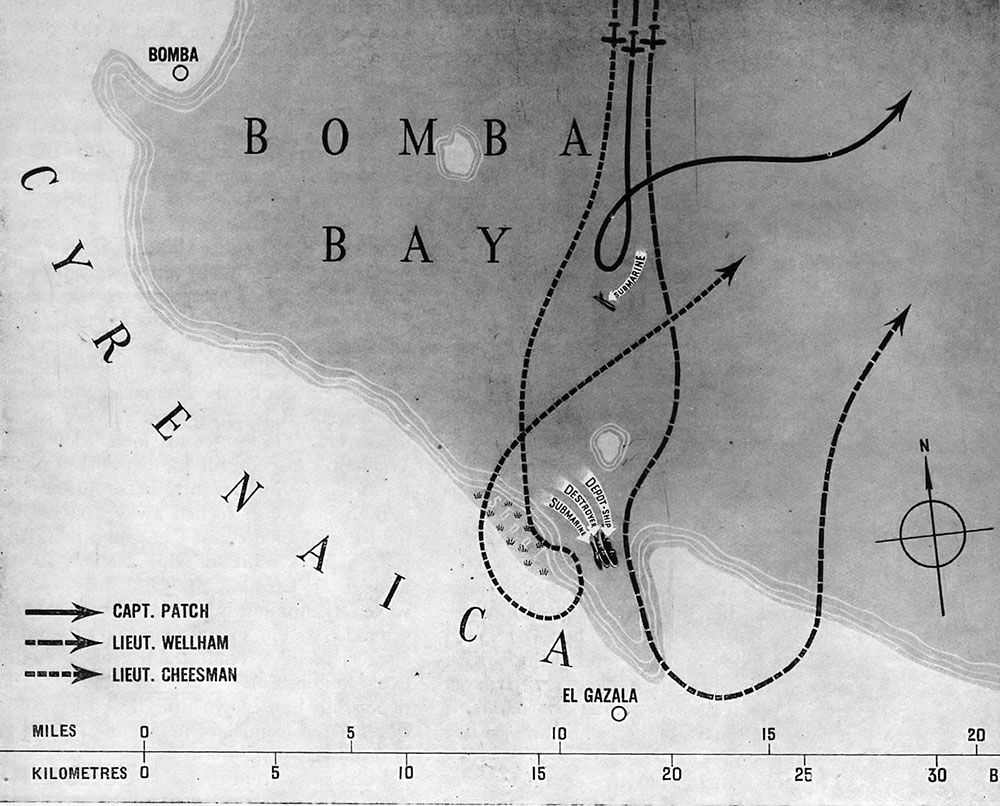

Part 99. From: Fleet Air Arm The Admiralty Account of Naval Air Operations published in 1943. THE SWORDFISH STRIKE IN BOMBA BAY “This attack, which achieved the phenomenal result of the destruction of four enemy ships with three torpedoes, was brilliantly conceived and most gallantly executed. The dash, initiative and co-operation displayed by the sub-flight concerned are typical of the spirit which animates the Fleet Air Arm squadrons of H.M.S. Eagle under the inspiring leadership of her Commanding Officer." Thus wrote Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, K.C.B., D.S.O., Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean Fleet, in a despatch from his flagship, H.M.S. Warspite, to the Secretary of the Admiralty. The sub-flight belonged to a Swordfish squadron which had disembarked to Dekheila airport when the aircraft-carrier Eagle (Captain A. R. M. Bridge, R.N.) was lying in Alexandria Harbour in August, 1940. After the squadron had been ashore a few days, Air Commodore R. Collishaw, Air Officer Commanding the Western Desert, applied for some torpedo-aircraft to help him deal with enemy shipping off the Libyan coast. He appreciated their potentialities the more because he had himself been a pilot in the Royal Naval Air Service during the last war, and later had served as Wing Commander in H.M.S. Courageous. One of the squadron observers was accordingly sent as Naval Liaison Officer to Ma'aten Bagush, the headquarters of the Royal Air Force in the Western Desert. Next day three Swordfish followed, accompanied by an aged Victoria aircraft carrying the maintenance ratings and a conglomeration of tool-boxes, chocks, torpedo-gear and spare parts. The R.A.F. officers welcomed the pilots and observers, and the ground staff took the naval mechanics under their wing. For the first few nights the sub-flight carried out anti-submarine patrols along the coast, without result. At 11 o'clock one evening the pilots were called to the Operations Room and told that the Blenheim dusk reconnaissance over Bomba Bay (between Tobruk and Benghazi) had reported a submarine depot-ship lying in the bay and a submarine heading in from seaward. Here was an ideal target for the torpedoes of the Swordfish. It was decided that the sub-flight should move up to Sidi Barrani next morning, re-fuel there, and await the report of the dawn reconnaissance. Early next morning, 22nd August, Captain Oliver Patch, Royal Marines, arrived by air from Dekheila. As the senior officer he took command of the sub-flight, which flew off for Sidi Barrani, armed with torpedoes, at 7 a.m. And here a word of praise must be given to Leading Torpedoman Arthey, who, in the words of one of the pilots, " during a week of blowing sand, had nursed his charges with such loving care that they ran with the smoothness of birds when at length we dropped them." After 90 minutes' flying, the Swordfish arrived over Sidi Barrani, which looked as though a tornado had passed over it. They succeeded in landing among the bomb craters without mishap. While the aircraft were refuelling, the crews were taken to the "Mess-cum-Ops Room," which one of them described as "a cunningly constructed edifice of petrol tins filled with sand, roofed by a tarpaulin, containing two wooden benches, a collection of camp stools, and an atmosphere of 85 per cent dust, 10 per cent tobacco smoke and 5 per cent air." There they had a breakfast of tinned sausages, with the inevitable baked beans of the desert, and bread liberally covered with marmalade dug out of a 4-lb. tin with the breadknife. The dawn reconnaissance showed that the targets were still in Bomba Bay. At 10.38 a.m. the sub-flight took off again and headed out to sea in V formation, led by Captain Patch. As his observer and navigator, Captain Patch had Midshipman (A) C. J. Woodley, R.N.V.R., who, although he was suffering from tonsillitis, had insisted on taking part in the raid. The Swordfish, flying low over the sea, shaped a course 50 miles from the coast, to avoid the attention of any prowling Italian fighters. At 12.30 they turned inshore and, thanks to Midshipman Woodley's accurate navigation, found themselves flying straight into Bomba Bay. They then opened out, fanwise, to about 200 yards. Four miles from the shore, in the centre of the bay, they sighted a large ocean-going submarine, dead ahead of the leader. She was steaming at about two knots on the surface, apparently charging her batteries. The crew's washing was hanging out to dry. Three miles beyond her, at the mouth of a creek known as An-el-Gazala, a cluster of shipping was visible. As the striking force approached, now flying only 30 feet above the sea, the submarine opened up a vigorous but ineffective fire upon the starboard aircraft with her two .5 machine-guns. The rear guns of the port and starboard aircraft replied. Captain. Patch turned swiftly to starboard, then smartly back to port, and dropped his torpedo from a range of 300 yards. On seeing the splash of the torpedo those of the submarine's crew who were on deck jumped into the sea. A few seconds later the torpedo hit the submarine amidships, below the conning-tower. There was a loud explosion, followed by a cloud of thick black smoke. The submarine blew up in many pieces. When the smoke had cleared away, only a small part of her stern was visible above the surface. Captain Patch, having completed his attack, turned out to sea again. The port and starboard aircraft, piloted by Lieutenant (A) J. W. G. Wellham, R.N., and Lieutenant (A) N. A. F. Cheesman, R.N., were now about a mile apart. They flew on towards the vessels lying inshore, which they identified as a depot-ship, a destroyer and another submarine, the destroyer being in the centre. The depot-ship opened fire with a few high-angle guns depressed along the surface. The destroyer joined in with her pom-poms and multiple machine-guns, and the submarine with her .5's. The fire was not concentrated, but a .5 bullet struck the bottom of the port aircraft, without wounding Lieutenant Wellham, however. He was not to discover the damage done to the aircraft until later. The two Swordfish closed the ships. Lieutenant Wellham, with Petty Officer A. H. Marsh as his observer, dropped his torpedo on the starboard beam of the depot-ship. As Lieutenant Cheesman was preparing to attack the submarine his observer, Sub-Lieutenant (A) F. Stovin-Bradford, R.N., noticed that they were over shoal water and, just in time, saved his pilot from leaving the torpedo in the sand. Lieutenant Cheesman was forced to fly in to 350 yards in order to let go in deep water. He could see the torpedo running the full distance until it hit the submarine amidships. She exploded instantly and set fire to the destroyer. Three seconds later Lieutenant Wellham's torpedo hit the depot-ship below the bridge. She began to blaze furiously. Both Swordfish turned away and headed for the sea, Lieutenant Cheesman making a right-hand circuit of the Italian fighter airfield at Gazala. He and his observer waved triumphantly to the airmen on the ground, but the enemy made no attempt to engage them. Then there was a terrific explosion astern. The magazine of the depot-ship had blown up. The three ships disappeared from sight in a cloud of steam and smoke. Forty miles from the coast the two Sword-fish sighted an Italian Cant Z 501 flying-boat above them, but it flew on towards Bomba without altering course. Shortly afterwards they made contact with their leader and reached Sidi Barrani at 3 p.m., having flown a total distance of 366 miles. Lieutenant Wellham's aircraft was found to be unserviceable: a bullet had smashed the extension to the main spar and knocked a dent in the petrol tank, fortunateiy without puncturing it. Lieutenant Wellham returned to Ma'aten Bagush in Captain Patch's aircraft. Midshipman Woodley was confined to sick quarters on completing his duty: apparently it was considered dangerous for him to be out of doors. Not unnaturally, the Operations Staff remained dubious about the crews' claim to have sunk four ships with three torpedoes, until the photographs of the reconnaissance Blenheim brought complete confirmation. Captain Patch was awarded the D.S.O., and the other pilots and the observers were also decorated. A few days after the raid the Italian Radio admitted the loss of four warships by "an overwhelming force of torpedo-bombers and motor torpedo-boats."  Neat as a pin. In this attack in Bomba Bay, Libya, on 22nd August 1940, a small striking force of Swordfish destroyed four enemy warships with three torpedoes. The submarine heading in from the sea was first to go. The aircraft on the right went on to sink the depot-ship lying at anchor. The second submarine was sunk by the remaining aircraft, and the explosion set fire to the destroyer in the middle.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3205279 - 02/11/11 06:08 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 100. Part 1 of the official account of the Battle of Britain. Published in 1941. THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN The Scene is Set On Tuesday, 20th August, 1940, at 3.52 in the afternoon, the Prime Minister gave the House of Commons one of those periodic reviews on the progress of the war with which members in particular and the country in general have grown familiar. The occasion was grave. On 8th August, the Germans, after a period of activity against our shipping, which had lasted for somewhat longer than a month, had launched upon this island the first of a series of mass air attacks in daylight. For some ten days, and notably on the 15th and the 18th, men and women in the streets of English towns and villages and in the countryside had seen high up against the background of the summer sky the shift and play of aircraft engaged in the fierce and prolonged combat which has come to be known as the Battle of Britain. The House was crowded. Its mood was one of anxious enthusiasm; but enthusiasm waxed and anxiety waned as the Prime Minister proceeded to describe the swiftly changing movements of the battle, the opening stages of which some of the members had themselves witnessed. After referring to the work and achievements of the Navy, Mr. Winston Churchill turned to the war in the air. "The gratitude of every home in our island," he said, "in our Empire and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen, who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of world war by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few." The Prime Minister was speaking at a moment when the battle was still at its height, for it was not until the end of October that the German Luftwaffe virtually abandoned its attacks by daylight and began to rely entirely on a policy of night raiding—its tacit admission of defeat. First Great Air Battle in History It is now possible to tell, in great part, the story of the action on which such high praise had been bestowed. Before doing so, however, it is worthwhile to recall the extraordinary nature of the battle. Nothing like it has ever been fought before in the history of mankind. It is true that aircraft frequently met in combat in the last war; but they did so in numbers very small when compared, with those which were engaged over the fields of Kent and Sussex, the rolling country of Hampshire and Dorset, the flat lands of Essex and the sprawling mass of London. Moreover, from 1914 to 1918 fights took place either between individual aircraft or between small formations, and an engagement in which more than a hundred aircraft on both sides were involved was rare even in the later stages of the war. The issue was, in fact, decided not in the air, in which element the rival air forces played an important but secondary part, but by slow-moving infantry in the heavy mud of Flanders and the Somme. It may be that the same thing, of something like it, will ultimately happen in the present war. Up to the moment, however, the first decisive encounter between Britain and Germany has taken place in the air and was fought three, four, five, and sometimes more than six miles above the surface of the earth by some hundreds of aircraft flying at speeds often in excess of three hundred miles an hour. While this great battle was being fought day after day, the men and women of this country went about their business with very little idea of what was happening high up above their heads in the fields of air. This was not shrouded in the majestic and terrible smoke of a land bombardment with its roar of guns, its flash of shells, its fountains of erupting earth. There was no sound nor fury-—only a pattern of white vapour trails, leisurely changing form and shape, traced by a number of tiny specks scintillating like diamonds in the splendid sunlight. From very far away there broke out from time to time a chatter against the duller sound of engines. Yet had that chatter not broken out, that remote sound would have changed first to a roar and then to a fierce shriek, punctuated by the crash of heavy bombs as bomber after bomber unloaded its cargo. In a few days the Southern towns of England, the capital of the Empire itself, would have suffered the fate of Warsaw or Rotterdam. The contest may, indeed, be likened to a duel with rapiers fought by masters of the art of fence. In such an encounter the thrusts and parries are, so swift as to be often hard to perceive and the spectator realises that the fight is over only when the loser drops his point or falls defeated to the ground. These were the Weapons Used Before we can understand the general strategy and tactics followed by both sides, something must be said of the weapons used. 'The Germans sought a decision by sending over five main types of bombers—the JU. 87, a dive-bomber, the JU. 88, various types of the Heinkel 111, the Dornier 215 and the Dornier 17. The JU. 87 type B was a two-seater dive bomber. It was an all-metal, low-wing cantilever monoplane, armed with two fixed machine guns, one in each wing, and a movable machine gun in the aft cockpit. When looked at from straight ahead the wings had the shape of a very flat W, Its maximum speed in level flight was a trifle over 240 miles an hour. The JU. 88 was also a dive bomber with a maximum speed of 317 m.p.h. Its crew and armament were similar to those of the Heinkel 111. The Heinkel 111k Mark V. was a low wing all-metal cantilever monoplane with two engines. It carried a crew of four and Was armed with three movable machine guns, one in the nose, one on the top of the fuselage and one in the streamlined “blister” underneath. Its maximum speed was nearly 275 m.p.h. The Dornier 215 was a high-wing cantilever monoplane of all-metal construction with three movable machine guns similarly placed to those of the Heinkel 111k. Its maximum speed was about 312 m.p.h. It was a development of the Dornier 17, familiarly known as “the flying pencil." This aircraft was a mid-wing cantilever monoplane. It was armed with two fixed forward-firing machine guns in the fuselage, one movable gun in the floor and one on a shielded mounting above the wings. Its maximum speed was about 310 m.p.h. Variations and increases in armament were constantly made in all these aircraft which carried the bombs intended to secure victory. These bombers were protected by fighters of which the Germans used two main types, the ME. 109 and the ME. 110. The ME. 109 in the form then used was a single-seater fighter. It was a low-wing all-metal cantilever monoplane armed with a cannon firing through the airscrew hub, four machine guns and two more in troughs on the top of the engine cowling. Its maximum speed was a little more than 350 m.p.h. Its pilot was later protected by back and front armour of which the size and shape became standardized during the course of the battle. The ME. 110 was a two-seater fighter powered with two engines. It was an all-metal low-wing cantilever monoplane with two fixed cannons and four fixed machine guns to fire forward from the nose. It was much larger than the ME. 109 but had not got the same capacity of manoeuvre. Its maximum speed did not exceed 365 m.p.h. In this aircraft the crew were protected by back armour only. The Germans also used a few Heinkel 113's. This was a low-wing all-metal cantilever monoplane with a single engine. A cannon fired through the airscrew hub and there were two large-bore machine guns in the wings. The maximum speed was about 380 m.p.h. To combat this formidable array of fighters and bombers, which Goring had boasted were "definitely superior" to any British aircraft, the Royal Air Force used the Spitfire, the Hurricane and occasionally the Boulton-Paul Defiant. The Spitfire. Mark I was a single-seater fighter with a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. It was a low-wing all-metal cantilever monoplane armed with eight Browning machine guns, four in each wing set to fire forward outside the airscrew disc. The maximum speed was 366 m.p.h. The Hawker Hurricane Mark I was also a single-seater fighter similarly engined and armed. Its maximum speed was 335 m.p.h. In both these aircraft the pilot was protected by front and back armour. The Boulton-Paul Defiant was a two-seater fighter with a Rolls-Royce engine. It was an all-metal low-wing cantilever monoplane, and was armed with four Browning machine guns mounted in a power-operated turret. With such machines as these the Royal Air Force and the Luftwaffe faced each other on 8th August when the battle began.

Last edited by RedToo; 02/11/11 07:03 PM. Reason: Typo.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3212017 - 02/19/11 10:08 AM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

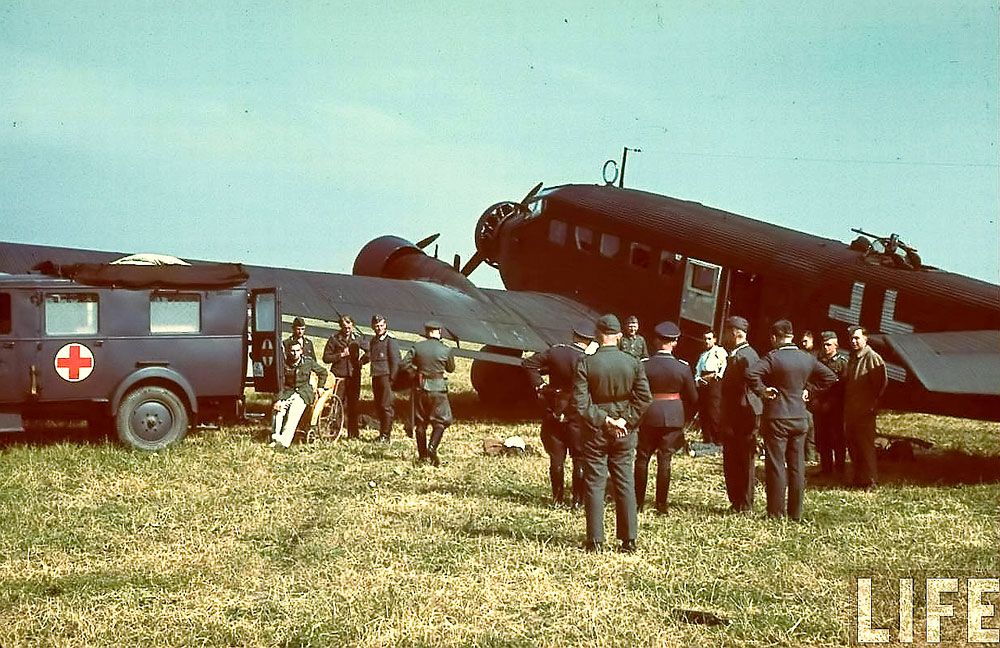

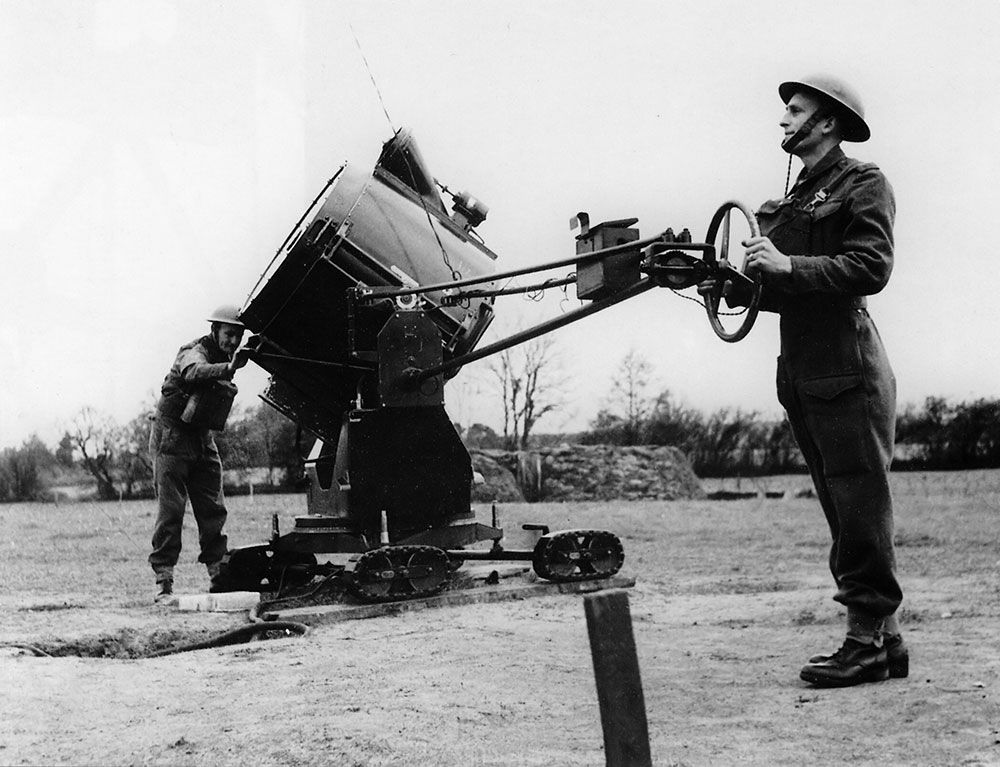

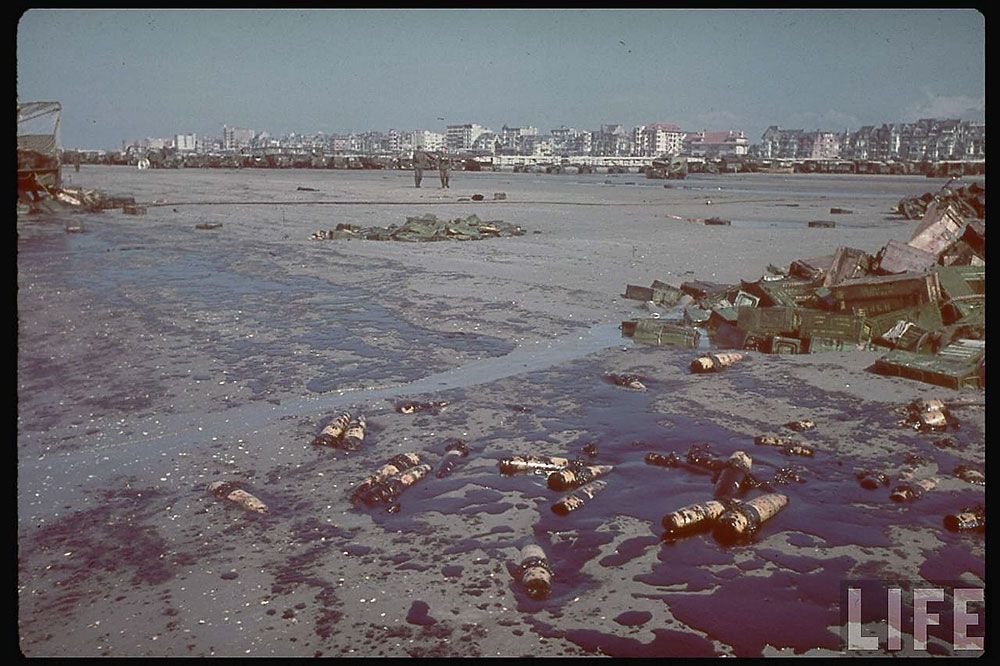

Part 101. Part 2 of the official account of the Battle of Britain. Published in 1941. The British Fighter Force on Guard Before describing it something must first be said about our methods of defence, although it is not easy to do this without giving away "state secrets." The governing principle is that a sufficient strength of Fighters must be assembled at the required height over a given place where it can intercept the oncoming enemy raid and break it up before it can reach its objective. There is general agreement that the principle of employing Standing Patrols is impracticable owing to its wastefulness. To keep a sufficient strength of Fighters always in the air to guard our shores from any attack would be beyond the powers of the biggest Air Force imaginable. The Fighter Force is therefore kept on the ground in the interests of economy of effort, and only ordered off the ground when raids appear to be imminent. Information regarding the approach of the enemy is obtained by a variety of methods and is co-ordinated and passed to "Operations Rooms." The coastline of Britain is divided into Sectors each with its own Fighter Aerodromes and Headquarters. These Sectors are grouped together under a conveniently situated Group Headquarters which in its turn comes under the general control of Headquarters, Fighter Command. The information about enemy raids is illustrated by various symbols on a large map table in Group and Sector Operations Rooms, the aim being to give each "Controller" the same picture of the progress of raids in his particular area. In addition to this the Controllers have all possible information set out before them, such as the location and "state" of their own Squadrons, the weather and cloud conditions all over their area. They are also in touch with Anti-aircraft Defences and Balloon Barrages. Squadrons are maintained at their Sector Aerodromes at various "states of preparedness." The most relaxed state is "Released," which means that the Squadron is not required to operate until a specified hour and that the personnel can be employed in routine maintenance, flying training and instruction, organised games, and that in some cases they may leave the Station. Next comes "Available," which means the Squadrons must prepare to be in the air within so many minutes of receiving the order. "Readiness" reduces this to a minimum and is the most advanced state normally used. Occasionally "Stand-by" is employed which means that the pilots are seated in their aircraft, with the engines "off," but all pointing into wind ready to start up, and take off, the moment the leader gets his orders from the Controller. In good weather conditions and when there is reason to anticipate an attack, Squadrons are perforce kept at a high state of "preparedness" which is relaxed as much as possible when the weather deteriorates. The broad principle is usually to keep one part of the force at "Readiness," a second part at "Advanced Available" and a third at "Normal Available." When the attack develops, the "Readiness" Squadrons are ordered off in appropriate formations and the "Available" Squadrons are ordered to "Readiness" and used as a reserve to meet a second or a third attack or to protect aerodromes or vulnerable points such as aircraft factories. These orders are issued by the Controller whose function it is to study the Operations Room Map and put a suitable number of aircraft into the air at selected points to intercept the oncoming raids, or to cover vulnerable points. His duty also is to keep a constant watch on his resources so as not to run the risk of being caught by a third or fourth wave of raids, with all his Squadrons on the ground "landed and refuelling." It must be remembered that the endurance of a modern Fighter aircraft, if it is to have ample margin for full throttle work, climbing and fighting, is limited. Allowance must also be made for the journey back to the parent station, especially if visibility is bad. With the tracks of the enemy raid and of his own Fighters both before his eyes, the Controller's task of making an interception is in theory a comparatively simple mathematical problem. He is in constant touch with his Fighters by radio telephone, is able to give them orders to change course from time to time, so as to put them in the best position for attack. Once the Fighters report that they have "sighted the enemy," the Controller's task is over, except that he may have to give them a course to bring them back to their aerodromes when the battle is over. The "enemy sighted" signal, the "Tallyho," is at once transmitted to Group H.Q. and recorded on the Squadron state indicator. The Red Letter day for any Group was on 27th September, when, in No. 11 Group, 21 Squadrons out of 21 ordered up were able to report "enemy sighted." But the successful interception of raids is not always so easy. In practice exercises before the war, thirty per cent, interception was thought satisfactory and fifty per cent, very good. When the test came, however, the percentage rose to seventy-five, ninety, and sometimes a hundred. This consistently high rate of interception made it possible for our superiority in pilots and aircraft to achieve its full effect. The task of the Controller in setting the stage for the battle is governed by one factor—accurate and timely information about the raids. In clear weather with little or no cloud, the raiders came over at such high altitude that they were almost invisible even with the use of binoculars. The numbers of aircraft employed made a confusion of noise in the high atmosphere and thus increased the difficulty of detecting raids by sound. In cloudy weather, this difficulty was increased, for the Observer Corps had then to rely entirely on sound. In view of these difficulties, that Corps and other sources of information deserve very great credit for the remarkably clear and timely picture of the situation they presented to the Controllers. These, then, set the pieces on the wide chessboard of the English skies and made the opening moves in the contest on the outcome of which the safety of all free peoples depended. Flexibility was their motto. Each day the Controllers held a conference at which every idea or device for thinking and acting one step ahead of their cunning and resourceful foe was set forth, earnestly discussed and, if found useful, adopted. Without this system of central control, no battle, in the proper sense of the word, would have taken place. Squadrons would have gone up haphazard as and when enemy raids were reported. They would either have found themselves heavily outnumbered or with no enemy at all confronting them. Great care was taken to keep the burden of the fight distributed as equally as possible between all the Squadrons engaged. This was achieved by hard training which continued right through the battle. Whenever there was a lull, new formations were devised and flown, new tactics practised. No Squadron was ever thrown into the fight without previous experience of fighting. They were carefully "nursed" and went into action under the leadership of an experienced squadron-leader with many hours of combat to his credit. The importance of team work was fully realised. It was a lesson learnt in France during the battles of May and June, and fortunately many of the pilots who had fought in them were in positions of command during the battle of Britain. Their knowledge and experience were invaluable. The German Command Plans a Knockout The avowed object of the enemy was to obtain a quick decision and to end the war by the autumn or early winter of 1940. To achieve this an invasion of Britain was evidently thought to be essential. Preparations to launch it were pushed forward with great energy and determination throughout the last days of June, the month of July and the first week of August. By the 8th August the enemy felt himself ready to begin the opening phase, on the success of which his plan depended. Before the German Army could land it was necessary to destroy our coastal convoys, to sink or immobilise such units of the Royal Navy as would dispute its passage, and above all to drive the Royal Air Force from the sky. He, therefore, launched a series of air attacks, first on our shipping and ports and then on our aerodromes. There were four phases in the battle, the first from 8th-18th August, the second from the 19th August-5th September, the third from the 6th September-5th October, the fourth from, the 6th-31st October. During this last phase daylight attacks gave way gradually to night raids which increased as the month went on. It should, however, be remembered that throughout the battle the enemy made use of night as well as day bombing, the first growing in volume and violence as the second fell away. What was the plan which he sought to carry through in these four phases? It is impossible to say with certainty at this moment. The German mind is very methodical and immensely painstaking. Schemes are worked out to the last detail; the organisation is superb and, provided the calculations are correct, the plan goes without a hitch. But again and again history has shown that, if the original plan fails or becomes impracticable, the German has little power of improvisation, and "if the trumpet give an uncertain sound, who shall prepare himself to the battle?" A brand new plan has to be worked out in full detail, and when this has been done it may well be too late. In this instance the Luftwaffe was designed to prepare the way for the German Army by smashing the enemy's resistance, and it was a fundamental assumption in Berlin that Germany could in every case establish and maintain air supremacy. The general plan for the use of the Luftwaffe was to seize and, exploit the full mastery of the air. This was the main feature in the Polish campaign, in the attacks on Norway and the Low Countries, and even to a large extent in France. Aerodromes were to be put out of action, thus tying the opposing Air Forces to the ground. Ports and communications could then be destroyed without hindrance, the military forces of the enemy paralysed and the German armoured divisions placed in a position to operate undisturbed. Success meant the destruction of civilian morale, and then internal disruption and surrender. PHASE I: THE OFFENSIVE IS LAUNCHED In the first stage the enemy sent over massed formations of bombers escorted by similar formations of single- and twin-engined fighters, The bombers were for the most part Ju. 87's (dive bombers), with a smaller quantity of He. 111's, Do. 17's and Ju. 88's. The fighter escorts flew in large, unwieldy formations, from 5-10,000 ft. above the bombers, where the protection they afforded was not very effective. Using these tactical formations the enemy made twenty-six attacks during this first stage. He began by renewing his assaults on our shipping. It may well be that this was still regarded as the most vulnerable form of target and the easiest to attack, for not only are slow-moving ships difficult to defend, but- casualties among the pilots of the defence are always higher when the action is fought over water. He may also have wished to test the strength of our general defences. Success against these would augur well for the next stage. At any rate, on 8th August two convoys were fiercely attacked, one of them twice. Sixty enemy aircraft in the morning and more than a hundred soon after midday, deployed on a front of over twenty miles, tried to sink or disperse a convoy off the Isle of Wight. They succeeded in sinking two ships. In the afternoon at 4.15 more than a hundred and thirty appeared over another convoy off Bournemouth. This they were able to disperse but they lost fairly heavily in doing so. The enemy renewed the assault three days later, choosing as his targets the towns of Portland and Weymouth, as well as convoys in the Thames Estuary and off Harwich. In these attacks he relied greatly on dive bombers, which proved no match for our Hurricanes. Nevertheless some damage was done both in Portland and Weymouth. This may have encouraged him, for on 12th August, early in the morning, he launched about two hundred aircraft in eleven waves against Dover. Shortly before noon a hundred and fifty more of the enemy attacked Portsmouth, and the Isle of Wight. By this time German losses were already very considerable, for one hundred and eighty-two aircraft had been destroyed. On the 13th and 15th the attacks on Portsmouth were renewed and in some of them, notably that which began soon after 5 in the afternoon of the 15th, between three and four hundred aircraft were employed. The enemy was by now beginning to realise that our fighter force was considerably stronger than he had imagined. It was evidently time to take drastic action. Our fighters must be put out of commission. Therefore, while still maintaining his attacks on coastal towns, he sent large forces to deal with fighter aerodromes in the South and South-East of England; Dover, Deal, Hawkinge, Martlesham, Lympne, Middle Wallop, Kenley and Biggin Hill were heavily attacked, some of them many times. A number of the enemy penetrated as far as Croydon. German Losses Run into Hundreds of Aircraft Once more the Luftwaffe did a certain amount of damage but at a cost which even Goring must have regarded as excessive. On that day, 15th August, a hundred and eighty German aircraft are known to have been destroyed. Since the opening of the battle he had now lost four hundred and seventy-two aircraft. Nevertheless he still returned to the charge, throwing in between five and six hundred aircraft on 16th August and about the same number on 18th. Rochester, Kenley, Croydon, Biggin Hill, Manston, West Malling, Gosport, Northholt and Tangmere, were the main targets, His losses were again very heavy. In those two days two hundred and forty-five aircraft were shot down. One of them, a Heinkel 111, fell to a Sergeant pilot flying an unarmed Anson aircraft of Training Command. Whether he intentionally rammed the enemy will never be known, for both aircraft fell to the ground interlocked and there were no survivors. On 18th August, in the evening attack on the Thames Estuary, one Squadron alone of thirteen Hurricanes shot down without loss an equal number of the enemy in fifty minutes. In the ten days since the opening of the attack on 8th August, Goring had now lost six hundred and ninety-seven aircraft. Our own losses during the same period were not light, for we lost one hundred and fifty-three. Sixty pilots were safe though some of them were wounded. The pace was too hot to last. Goring called halt and gave his Luftwaffe a rest which lasted for five days. What had he hoped to achieve? An examination of the attacks shows that he began by trying to destroy shipping and ports on the South-East and South Coasts between the North Foreland and Portland. This preliminary test must have shown him the strength- of our defences. Nevertheless he proceeded with his plan and next directed his attention to Portland and Portsmouth. Whether these objectives were too tough for him or whether he thought that the four heavy attacks upon them had accomplished his object, he turned away to deliver assaults on fighter and bomber aerodromes mostly near the coast. Throughout this first stage the tactics he followed were usually to open his attack on objectives near the coast in order to draw off our lighters. These feint attacks were followed thirty or forty minutes later by the real attack delivered against ports or aerodromes on the South Coast between Brighton and Portland. The chief problem created by these tactics was to have a sufficient number of fighters ready to engage the main attack as soon as it could be picked out. Squadrons at the forward aerodromes had to be in instant readiness, but had at the same time to be protected from bombing or machine-gun attacks. Only on one occasion was a Squadron machine-gunned while re-fuelling at a forward aerodrome, and this happened because a protective patrol had not been maintained overhead during the process. Generally the enemy attacks were countered by using about half the available Squadrons to deal with the enemy fighters and the rest to attack the enemy bombers which flew normally at from 11-15,000 feet, descending frequently to 7,000 or 8,000 feet in order to drop their bombs. Our fighter tactics at this stage were to deliver attacks from the stern on the Me. 109's and Me. no's. This type of attack proved effective because these aircraft were not then armoured. The success of our fighter tactics at this stage can be gauged by a comparison between our losses in pilots and those of the enemy. The ratio was about seven to one and might have been even more striking if so much of the fighting had not taken place over the sea. PHASE II: THE ATTACK ON INLAND AERODROMES Between the end of the first stage and the active beginning of the second there was, as has been said, an interval of five days which were spent by the Germans in wide-spread reconnaissance by single aircraft, some of which indulged in the spasmodic bombing of aerodromes. These operations cost them thirty-nine aircraft shot down, our losses were ten aircraft, but six pilots were saved. During this lull, Goring evidently decided that a change of objectives was necessary. Perhaps he thought that he had achieved the necessary results, and that Portland and Portsmouth together with our coastal aerodromes were virtually out of action. Perhaps he was under the impression that inland aerodromes, factories and other industrial targets would not be as stoutly defended. It is more probable, however, that he merely gave the order for the second part of the plan to be put into operation and disregarded the failure of the first part—either deliberately, or because he had no alternative. In this next stage diversionary attacks against different parts of the country became less frequent. The main attack was now delivered oil a wider front. Enemy tactics were also changed. The number of escorting fighters was increased and the size of bomber formations reduced. The covering fighter screen flew at very great heights. Enemy bomber formations were also protected by a box of fighters, some of which flew slightly above to a flank or in rear, others slightly above and ahead, and yet others weaving in and out between the sub-formations of the bombers. This type of formation succeeded on several occasions in breaking through the forward screens of our fighter forces by sheer weight of numbers and in attaining their objectives even after numerous casualties had been inflicted. On other occasions smallish formations of enemy long-range bombers deliberately left their fighter escort as soon as it had joined battle and proceeded towards South or South-West London unaccompanied. They suffered heavy casualties when engaged by our rear rank of fighters. Having thus altered his tactical formations the enemy proceeded to deliver some thirty-five major attacks between the 24th August and 5th September. His object, as has been said, was to put out of action inland fighter aerodromes and aircraft factories. He did not, however, disdain purely residential districts in Kent, the Thames Estuary and Essex, These could in no case be described as of military importance. Eight Hundred Aircraft Attack Fighter Aerodromes From 24th to 29th August he still showed an interest in Portland, Dover and Manston, all of which were heavily attacked. He added other targets as well. Several areas in Essex came in for attention. There was fierce fighting over the North Foreland, Graves-end and Deal. At 6.45 p.m. on the 24th, a hundred and ten German bombers, and fighters met a number of our Squadrons in the neighbourhood of Maidstone but turned and fled before they could be engaged. The next day he returned to Portsmouth and Southampton where once again he achieved no success, the main attack, delivered at 4 p.m., going astray. A large number of bombs fell into the sea. Heavy assaults were also made in the Dover-Folkestone area, and over the Thames Estuary and in Kent. These continued with a lull of one day until 30th August. On that day and the next the assault was switched to inland fighter aerodromes. Eight hundred aircraft were used in a most determined effort to destroy or temporarily put out of use the aerodromes at Kenley, North Weald, Hornchurch, Debden, Lympne, Detling, Duxford, Northolt and Biggin Hill. The opening of September showed little, if any, falling off in the assaults of the enemy. There were three heavy attacks on 1st September, five on 2nd, one on 3rd and two on 4th and 5th. One of the attacks on the 2nd got to within ten miles of London, but most of them were once again directed against fighter aerodromes. This was the last of the thirty-five main attacks delivered in this phase. They cost the Germans five hundred and sixty-two aircraft known to have been destroyed. Our own losses were two hundred and nineteen aircraft, but a hundred and thirty-two of their pilots were saved. During these twelve days, our own tactical dispositions were altered so as to meet the changed form of attack. The effect of this was to cause the enemy to be met in greater strength and farther away from their inland objectives, while such of his aircraft as were successful in eluding this forward defence were dealt with by Squadrons farther in the rear. The heavy task of the defence can be realised by the fact that in these first two phases of this great battle from the 8th August to 5th September inclusive, no fewer than 4,523 Fighter Patrols of varying strength in aircraft were flown in daylight, an average of one hundred and fifty-six a day. Hurricanes and Spitfires Stay in the Air What did the enemy succeed in accomplishing in just under a month of heavy fighting during which he flung in squadron after squadron of the Luftwaffe without regard to the cost? His object, be it remembered, was to "ground" the Fighters of the Royal Air Force and to destroy so large a number of pilots and aircraft as to put it, temporarily at least, out of action. As has already been made clear, the Germans, after their opening heavy attacks on convoys and on Portsmouth and Portland, concentrated on fighter aerodromes, first on, or near the coast, and then on those farther inland. Though they had done damage to aerodromes both near the coast and inland and thus put the fighting efficiency of the Fighter Squadrons to considerable strain, they failed entirely to put them out of action. The Staff and ground services worked day and night and the operations of our Fighting Squadrons were not in fact interrupted. By the 6th September: the Germans either believed that they had achieved success and that it only remained for them to bomb a defenceless London until it surrendered, or, following their pre-arranged plan, they automatically switched their attack against the capital because the moment had come to do so. Those days saw the climax of the first half of the battle. As they drew to a close Goring's position became not unlike that of Marshal Ney at Waterloo, when at 4.30 in the afternoon he flung thirty-seven squadrons of Kellermann's Cuirassiers, backed by the Heavy Cavalry of the Guard against the hard-pressed British squares. Napoleon was unable to find the necessary support and Ney's effort was made in vain. Goring may perhaps have been in the same position, though the attacks of the Luftwaffe continued to be pressed hard throughout September. It may be that Goring had made up his mind to attack targets more easily reached than were our fighter aerodromes. It may be that he was merely working to a time-table. It may be that he thought that our fighter defence was sufficiently weakened. What probably happened can be conveyed by a simple analogy. Imagine a game which involves knocking down a number of objects such as nine-pins or skittles, in so many turns. The player has worked out a detailed scheme for attacking these by stages. The first two or three, shots, however, result in misses, and the prudent man would pause to reconsider his policy at this point. Can he pursue his scheme and still win, or must he abandon it and try another? But this player, Goring, is so certain of winning that he goes on without stopping to think whether or not the preliminary shots have been successful. Suddenly he realises that, with only one or two turns left, he cannot possibly win on the lines of his pre-arranged scheme and he makes a desperate effort to knock down the whole set in the last few shots. This may be no more than a speculation. The facts are that on 7th September Goring switched his attack away from fighter aerodromes on to industrial and other targets, and he began by making London his main objective.    France 1940. Three great colour pics from this site: http://www.thefewgoodmen.com/thefgmforum/forum.php?Scroll down to the WWII section then aviation. Site found by TungstenKid and posted in the General Discussion Ubizoo thread. Thanks TungstenKid.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3218307 - 02/25/11 05:48 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

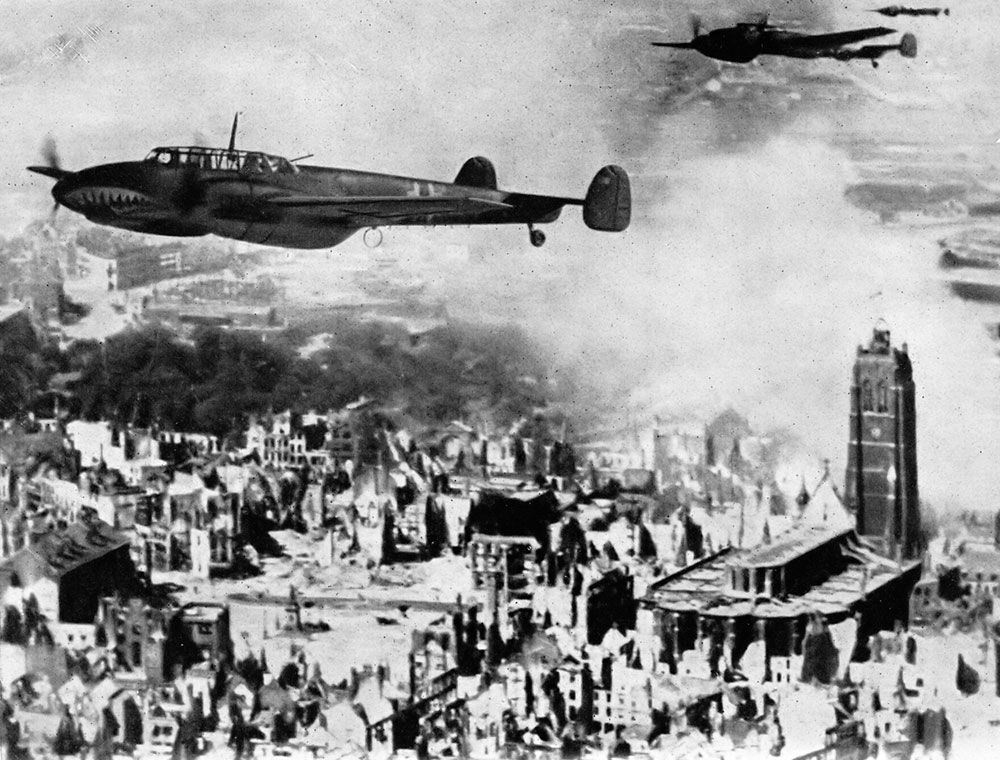

Part 102. Part 3 of the official account of the Battle of Britain. Published in 1941. PHASE III: LONDON versus GORING The attacks on London on 7th September were made in two or three distinct waves at intervals of about twenty minutes, the whole attack lasting up to an hour. The waves were composed of formations of from twenty to forty bombers with an equal number of fighters in close escort, additional protection being given by large formations of other fighters flying at a much higher altitude. Most of the German aircraft came over at heights above 15,000 feet in sunny skies which made the task of the Observer Corps very difficult. At this stage, too, the enemy's dive bombers reappeared in attacks on coastal objectives and shipping off Essex and Kent. They were a diversion for they came over while the mass attacks by the long-range bombers were in progress. By night the Germans greatly increased their attacks by single aircraft. These made no attempt to hit military targets, but contented themselves with dropping their bombs at random over the large area of London. All the attacks, however, were in essence the same. Over came the German aircraft in one or more of the many formations already described. Somewhere between the coast and London, usually in the Edenbridge-Tunbridge Wells area, but sometimes nearer to the sea, the German squadrons were met by our fighters. The Spitfires tackled the high-flying fighter screen covering the German attack. The Hurricanes, which had taken off first, engaged the fighter escort, followed by other squadrons who went for the bombers. There were dog-fights all over Kent. The air was for some minutes—never for very long—vibrant with machine-gun fire. People on the ground have described it as like the sound made by a small boy in the next street when he runs a stick along a stretch of iron railings. As a background there was the faint roar of hundreds of engines which on occasion swelled to a fierce note as some crippled enemy fighter or bomber fell to the ground or made for its base dropping lower and lower with Spitfires or Hurricanes diving upon it. Sometimes watchers, like those upon the keep of Hever Castle, would see the blue field of the sky blossom suddenly with the white flowers of parachutes. The warm sun of those superb September days shone on an ever-increasing number of the wrecked carcases of aircraft bearing on their wings the Black Cross of Prussia or the crooked symbol of Nazi power. The Last Throw The attack on London and its environs was the crux of the battle. It continued with little respite from the 7th September until 5th October and was the last desperate attempt to win victory. This could no longer be achieved cheaply, for the Luftwaffe had already suffered terrible losses. But it might still be possible to destroy London and thus to Win the war. Despite the hard fighting of the previous month the Fighter defences of the R.A.F. were still fighting as hard as ever. They had to be overcome before London could be placed at Hitler's mercy. Goring still believed in superior numbers, these would win the trick. They had brought him swift victory in Poland, Norway, the Low Countries, Belgium and France; they might still bring victory in Britain. He put forth all his strength in a final endeavour to knock down the nine-pins at any cost. The Luftwaffe delivered thirty-eight major attacks by day between the 6th September and 5th October. After battering away morning, noon and night throughout the 6th September against our inland fighter aerodromes, the German Air Force made a tremendous effort on the 7th to reach London and destroy the Docks. Three hundred and fifty bombers and fighters flew in two waves East of Croydon up to the Thames Estuary, some penetrating, nearly as far as Cambridge. They were met over Kent and East Surrey, but a number broke through and were engaged over the capital itself. For the first time since that September day in 1666, when Mr. Samuel Pepys informed the King at Whitehall that the City was on fire, Londoners saw flames leaping up from various points in the crowded and densely populated districts of Dockland and Woolwich, while from every German radio station announcers broadcast a running commentary On the action, in which imagination and wishful thinking were nicely blended. London did not emerge unscathed. Damage was inflicted on dock buildings, on several factories, on railway communications, on gas and electricity plants. It was also inflicted on the enemy. One hundred and three German aircraft were destroyed. These heavy casualties shook the German High Command, for though the attacks were renewed and continued, evidently all was no longer well. Still, the Luftwaffe persevered with great tenacity and courage, delivering heavy attacks on 9th September, using on that occasion a number of four-engined bombers; on the 11th, when about thirty aircraft penetrated to Central London; on the 13th and again on the 15th. Those who got through on the 11th were so savagely handled by our fighter defence that the losses among their crews were estimated to be not less than two hundred and fifty. On the next day a single German aircraft penetrated the defence by the clever use of cloud cover and bombed Buckingham Palace in the morning. On the 15th September came the climax; five hundred German aircraft, two hundred and fifty in the morning and two hundred and fifty in the afternoon, fought a running fight with our Hurricanes and Spitfires from Hammersmith to Dungeness, from Bow to the coast of France. This engagement will be described in greater detail later. It cost the enemy one hundred and eighty-five aircraft known to have been destroyed. Altogether, between the 6th September and the 5th October, he had lost eight hundred and eighty-three aircraft. It is not necessary to record in detail the rest of the fighting which; endured to 31st October. Enough has been said to show the nature of the German effort and of our defence. There were, however, three more major assaults delivered, on 27th September, 30th September and 5th October. Thus between 11th September and 5th October the enemy delivered some thirty-two major attacks by day. In all these, bombers were used and their escort of fighters steadily increased in numbers, till the ratio rose to four fighters to one bomber. Of these attacks fifteen were made on the area of Greater London, ten against Kent and the Thames Estuary, six on Southampton and one on Reading. While these last attacks were well executed and pressed home, those on London were less determined than in the opening stages of the battle. On many occasions the enemy jettisoned his bombs before reaching his apparent objective as soon as he found himself in contact with our fighters. Throughout this period the bombing attacks were mostly made from high level. To enable their bombers to reach their targets the Germans sought to draw off our fighter patrols by high altitude rather than by geographical diversions. High fighter screens were sent over, to occupy our fighters while the bombers closely escorted by more fighters tried to get through some 6,000 to 10,000 feet below. Success of British Fighter Interception As autumn came on and the sky grew more cloudy, the enemy began to make increasing use of fighters flying very high above the clouds; His most usual practice was to put a very high screen of these fighters over Kent from fifteen minutes to three-quarters of an hour before his bombers appeared. The object was evidently to draw off our fighters, exhaust their petrol and thus make it impossible for them to engage the bombers. Sometimes, however, the high-flying enemy fighters appeared only a few minutes before the bombers, which were themselves escorted by other fighters; These escorts were normally divided into two parts, a big formation above and on both flanks or rear of the bombers, and a small formation on the same level as, or slightly in front of, the aircraft they were protecting. The enemy's high fighter screen was engaged by pairs of Spitfire Squadrons half-way between London and the coast while wings of two or three Hurricane Squadrons attacked the bombers and their escorts before they reached the fighter aerodromes East and South of London. Other Squadrons formed a third and inner ring patrolling above these aerodromes forming a defensive screen to guard the southern approaches to London. These intercepted the third wave of any attack and mopped up the retreating formations belonging to earlier waves. The success of these tactics may be gauged by the number of casualties inflicted on the Germans. Between 11th September and 5th October, No. 11 Group of Fighter Command alone destroyed four hundred and forty-two enemy aircraft for certain. This was accomplished with the loss of fifty-eight pilots, giving a ratio of seven and a half enemy to one British pilot lost. September came and went and by the end of the first week in October our aerodromes had recovered from the damage inflicted on them at the end of August and the beginning of September. The percentage of raids intercepted increased, as did the casualties of the enemy, while our own steadily decreased. Thus on 27th September No. 11 Group destroyed ninety-nine German aircraft, out of a total for the day of one hundred and thirty-three, for the loss of fifteen pilots, a proportion of six and a half to one. Three days later, when thirty-two enemy aircraft were destroyed, the proportion rose to sixteen to one, and on 5th October only one pilot was lost though twenty-two of the enemy were shot down. Many times one aggressively-led squadron was able to break up an enemy bomber formation. On three occasions a lone Hurricane flown by a Sector Commander was successful in causing the enemy to drop his bombs wide of the target. The brunt of all this fighting fell on No. 11 Group. This Group was reinforced when necessary by elements of Numbers 10 and 12 Groups, which were especially useful during the period of the heavy attacks on London. How hard fought was the battle can be seen from the fact that from 8th September to 5th October inclusive, 3,291 day patrols of varying strengths were flown, and from 6th October to the last day of that month 2,786, making a total for these fifty-five days of 6,077. PHASE IV: THE LUFTWAFFE IN RETREAT On 6th October, the fourth and final stage of the battle began. The enemy's strategy and method of attack now changed completely. He withdrew nearly all his long-range bombers and tried to achieve his end by means of fighters and fighter bombers. This change is the surest proof that he had received such a hammering as to make further use of his depleted bombing force by daylight too costly. He preferred to send it over by night, and this he did in increasing numbers. His tactical handling of his fighters and fighter bombers—a few of them were Me. 110's but they were mostly Me. 109's fitted with a make-shift bomb carrier enabling them to take a pair of bombs at a speed of about three hundred miles an hour— was this. Mass fighter formations were sent over at a great height in almost continuous waves to attack London, still the principal target. He doubtless hoped by this means to wear out our fighter defence by forcing it to engage, at much higher altitudes, aircraft which were making the best use possible of high cloud cover. In the early stages he reduced the size of his formations and used flights of from two to nine aircraft. The fighter bombers were protected more and more by Me. 110 fighters. Evidently, however, this new plan did not achieve the success for which he hoped, for in the third week of October he reverted once more to large formations flying at 30,000 feet or higher. To enable them to break through, the Germans continued to use the tactics of diversion. Whenever the weather was good enough waves of fighters appeared almost continuously over the South-East of England. Using the cover these provided, very high flying fighter bombers made frequent and rapid attacks on the London area. On sighting our fighters, however, they often jettisoned their bombs and made off. They showed, in fact, little tendency to engage, but when they did so they sometimes gained the advantage of surprise owing to the height at which they were flying. The Last Move Countered Our own tactics were immediately altered so successfully that No. 11 Group accounted for one hundred and sixty-seven enemy aircraft in three and a half weeks. The cost to the Group was forty-five pilots. In this phase the number of enemy probably destroyed rose considerably, because the fighting took place so high up that our pilots were unable to see the ultimate fate of many of the German aircraft which fell away after the encounter towards the sea. The physical strain of fighting at heights of 30,000 feet or more proved very severe. It is possible to detect a feeling of despair in the hearts of the Luftwaffe during this final phase of the struggle. Try as they might, and did, our defences were still not only intact but invulnerable. Occasionally an odd Me. 109 or a small formation broke through and reached London, but the weight of the bombs which they succeeded in dropping was only a fraction of what had been dropped in August and September. Moreover, there was little attempt at precision bombing. There can be no better proof of the enemy's failure than that furnished by the citizens of London. During the early stages, many of them took cover when the sirens sounded. Post Offices, Ministries and Public Departments, large stores—all closed their doors and sent their staffs and any visitors in the building to cover. Very soon, however, it was noticed that most of the noise, at no time to be compared with the nightly barrage which soon became the background of their slumbers, was due to gunfire and not to the explosion of bombs. Trails of white vapour forming fantastic and beautiful patterns in the summer sky were often the only indication that the Luftwaffe was over the capital. These pleased the eye and provided a subject for speculation in the streets and public resorts. Soon, however, even these failed to attract much notice. As the days wore on the Londoner, always confident in the ability of the Royal Air Force to protect him in the hours of daylight, began to take that protection for granted. Except when roof-watchers—the Prime Minister's "Jim Crows" —signalled that danger was imminent, life went on as usual and still does. There can be no better tribute to the men of the Fighter Squadrons.   Heinkel He 111’s in France 1940.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3225032 - 03/05/11 11:24 AM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|