|

#3091307 - 09/10/10 09:10 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

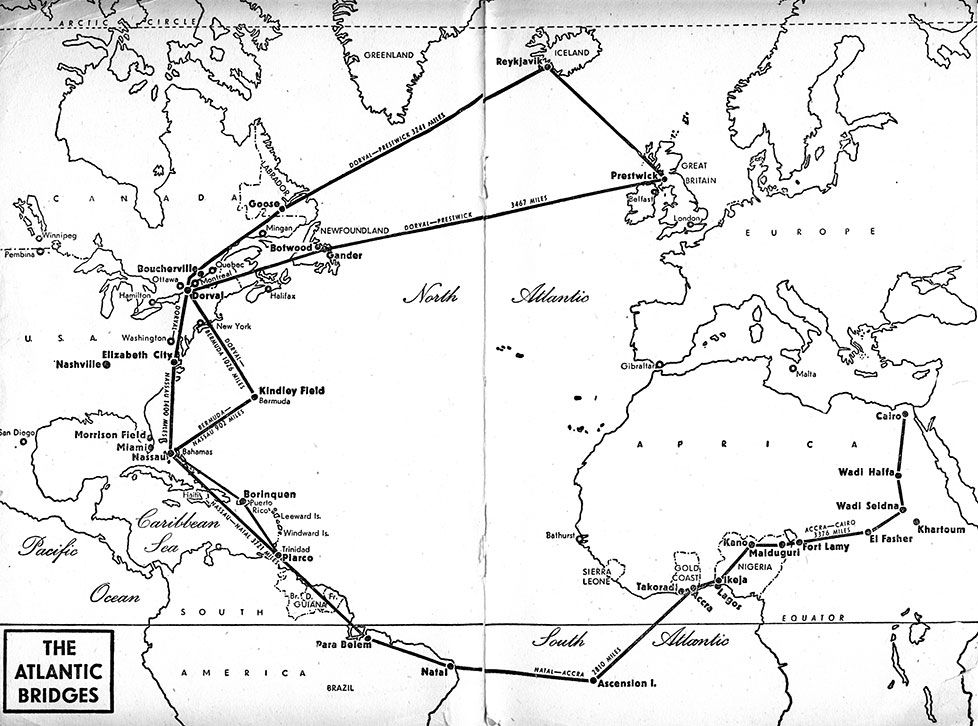

Part 78. 4. Fortress Raider Several other attacks were made in the course of the afternoon. A fortress aircraft reached Emden, and found fine weather over the target. Bombs were seen to burst in the target area, and smoke curled up from the ground far below. (Air Ministry Bulletin.) I HAVE flown in the sub-stratosphere in a Fortress bomber over Holland, France, Norway and Germany. If the people on the ground in those countries have seen us at all, we have appeared no more than the tiniest dot in the sky. Their largest towns to us have seemed no bigger than a sardine tin laid flat on the perspex. On your first ascent, you are very much aware of flying in unexplored space, relying completely on oxygen, but after a few trips you become accustomed to new colours in the sky; and when from one point, only a hundred miles from the English coast, you can see right across Denmark into the Baltic, and into Germany by Hamburg, and the whole plain of Holland is spread out in front of you, you do little more than note it in your log. To us who have carried out a good many attacks on the enemy, our Fortress seems no more difficult or less reliable than a good old Lysander at 1,000 feet. It's all a question of what you get used to. Before coming to our attack on Emden last week-end, I should like to give you two instances of why we have learned to have this trust in the Fortresses. I was in the Fortress which was attacked by seven fighters when we were returning from Brest. Three minutes after our bombs had gone, the fire controller called out that there were seven enemy fighters coming up to us from the starboard quarter, 1,000 feet below. They closed in and there was almost no part of the Fortress which was not hit. Some of my friends in the crew were killed, others wounded. A petrol tank was punctured, bomb doors were thrown open, flaps were put out of action, tail tab shot away, tail wheel stuck half down, brakes not working, only one aileron any good and the rudder almost out of control. The centre of the fuselage had become a tangle of wires and broken cables, square feet of the wings had been shot away, and still the pilot managed to land the Fortress on a strange aerodrome. There is a testimony to the makers in America. Another time, when we were coming away from Oslo, part of the oxygen supply ceased and the pilot had to dive down swiftly through 19,000 feet. He pulled out and the Fortress landed safely at base. There is proof of the strength of the Fortress's construction. Fortunately these thrills are rare. Our attack on Emden last week-end was almost without incident, except, of course, for the dropping of the bombs by the Sperry sight with beautiful accuracy on the target. It was, in fact, a typical Fortress raid. We lost sight of the aerodrome at 2,000 feet, and never saw ground again until we were off the Dutch islands. Foamy white cloud, like the froth on a huge tankard of beer, stretched all over England and for about thirty miles out to sea. The horizon turned�quite suddenly�from purple to green and from green to yellow. There was a haze over Germany, but I could see Emden fifty miles away. I called out to the pilot, in the sort of jargon that we use in the air, " Stand by for bombing, bomb-sight in detent, George in, O.K., I've got her." Then the pilot says to me," Let her go." The drill is that I push a lever on my left for the bomb doors to open, and on a dial in my cabin two arms move out like the hands of a clock to show me the position of the bomb doors. On and around the Sperry sight there are eleven knobs, two levers and two switches to operate. On the bombing panel there are five switches and three levers to work and the automatic camera to start. I keep my eye down the sighting tube which, incidentally, contains twenty-six prisms, and with my wrist I work the release. As the cross-hairs centred over a shining pin-point in Emden on which the sun was glinting, the bombs went down. The pilot was told by means of an automatic light which flickered on as they dropped. We were still two miles away from Emden when we turned away. One of the gunners watched the burst. Almost a minute later he told us through the inter-com., "There you are, bursts in the centre of the something target," and back we came through those extra�ordinary tints of the sky. Over England there was a strange scene that I have noticed before. The cloud formation exactly compared with the land below. Every bay and inlet was repeated in the strata-cumulus thousands of feet above, like a white canopy over the island. During the whole sortie I had only one thrilling moment. I saw a Messerschmitt coming towards us. He seemed an improved type, and I looked again. It was a mosquito which had got stuck on the perspex in the take-off and had frozen stiff. The windows usually are splashed with insect blood, but this fellow had seemed the right shape for a Hun. Otherwise it was an uneventful, typical trip in a Fortress, with the temperature at minus 30 degrees below zero Centigrade. To add to the above account it is interesting to read the following about what we now call the Flying Fortress, printed in �The Royal Air Force In Pictures� published in September 1941: THE BOEING FORTRESS THE Boeing Fortress achieved lasting fame in the military aircraft class when, in the hands of Royal Air Force personnel, it introduced in the summer of 1941 the tactics of the sub-stratosphere attack. At the time it was the highest-flying heavy bomber in service in any air force in the world, and its service ceiling with full load of 36,700 feet put it outside the range of most enemy fighters within the time period available to them. Enemy aircraft such as the Messerschmitt I09F could climb higher than the Boeing, but during the climb the Boeing was often able to discharge its bombs on the targets and make good its return. Particularly satisfying as an aeroplane with a well-streamlined fuselage of circular section, the Boeing is powered with four Wright Cyclone engines each of 1,200 horse power, and each fitted with an exhaust-driven supercharger. In the working of these exhaust-driven superchargers lies the reason for the Fortress's specially well-developed high-flying qualities. Many of the early sorties of the Boeing Fortresses were made without a single interception by the enemy, but on August 16, 1941, when a raid was being made on Brest, a Fortress was attacked by seven enemy fighters, two Heinkel 113's and five Messerschmitt l09F's. The Fortress was damaged and three members of the crew severely wounded, but after twenty minutes' fighting it managed to shake off the enemy aircraft and to return to England. The Fortress is a semi-monocoque structure with wings of aluminium alloy and stressed skin covering. Wing flaps and undercarriage retracting gear are electrically operated. The airscrews are Hamilton Standard Hydromatic full-feathering. The wing span is 103 feet 9 inches, and the length 67 feet 11 inches. The maximum gross weight is 47,500 lb. Top speed is 325 miles an hour and the maximum range 3,500 miles. At 25,000 feet the aircraft is still climbing at a rate not far short of 1,500 feet a minute. As the first specialised sub-stratosphere heavy bombing aircraft the Boeing Fortress takes its place in aviation history. It carries seven guns, some of heavy calibre. There are flank, nose and under-tail positions.   The pictures are from the same book and show the Fortress in RAF use. All in all a harbinger of what was to come.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3095948 - 09/17/10 08:58 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

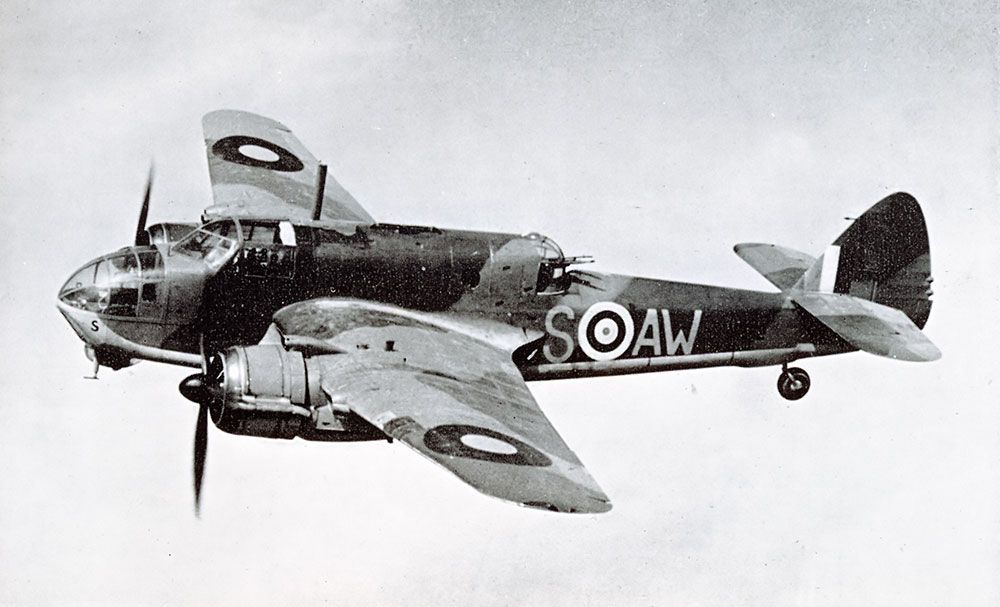

Part 79. 5. Beaufort v. Battleship Shortly before midnight last night (Thursday) a Blenheim aircraft of coastal command on reconnaissance off the southern coast of Norway sighted an enemy pocket battleship escorted by a number of destroyers. A striking force was despatched by coastal command and in the early hours of this morning the battleship, then off Egersund, was hit by a torpedo from a Beaufort aircraft. Dense clouds of white smoke rose from the vessel and prevented accurate observation by other aircraft of the results of their attacks. (Air Ministry Communique.) FRIDAY, JUNE 13TH was not a lucky day for the German Navy. A Coastal Command Beaufort aircraft, of which I was the pilot, obtained a direct hit with a torpedo on a German pocket battleship as it was slinking out past Norway, and sent it, with its attendant destroyers, back home. When it was getting near midnight on Thursday we had orders to push off with other aircraft from the squadron. Somebody mentioned that it would soon be the 13th, and when my wireless operator found that we had to take pigeon container No. 13 he said, �We�re bound to be lucky." Carrying our torpedo slung beneath us, we started off in formation. There was a bit of moon, but it was partly obscured and shone through the haze only occasionally. In some patches of cloud you could see hardly anything, but it was fairly light in the clear spaces. We were well over the North Sea when midnight came. We were flying pretty high as we approached the coast of Southern Norway and found several gaps in the clouds where the moon was breaking through. You could see the surface of the water and, as we came into one of these clearings, we suddenly spotted a formation of enemy warships away down under the star-board wing. The white washes trailing behind them caught our eyes first, and then we saw the ships' small black slim shapes. They were arranged in a very nice formation with the pocket battleship in the middle and her five escorting destroyers dispersed around her. One destroyer was right ahead of the battleship and there were two more destroyers on each side, making a pretty effective screen. We dived to get into position from which to attack. We came down to a few hundred feet above the sea and flew at right angles across the stern of two destroyers bringing up at the rear. That put us on the broadside of the formation. We made a right-about turn to starboard and came straight back on its beam. There was not much time to think about attacks. One destroyer was right in our way and I had to skid round its stern to get a suitable angle to drop. We were close enough to the destroyer to see the design of its camouflage, outlines of the deck fittings, and even the rail. The next second I put the nose of the aircraft round and saw the battleship in my sight. I pressed a button on the throttle which released the torpedo�and away it went. As soon as the torpedo had gone I made a sharp turn to port and opened my engine flat out. I was expecting a barrage of flak at any moment. The navigator beside me was looking back at the ship saying, �It�s coming, it's coming." But fortunately the flak did not come, not even when, for one unpleasant moment, we found ourselves in a vertical turn round one of the destroyers where we should have been easy meat. I think our attack must have taken them completely by surprise. All this time the torpedo was running on its course and really only a few seconds had elapsed. As we flew clear from the ship, the rear gunner and the wireless operator shouted together over the inter-com., �You�ve hit it. There's a great column of water going up, and dirty white smoke." I flew round in a circle to see for myself, and sure enough there was plenty of smoke and a patch of foam on the ship's track. Naturally I didn't want to hang around too long, so when we were satisfied with the results of our attack, we made a signal reporting it. When we got back home we heard that other aircraft had found the German force after we had attacked it. The ships had stopped by then and were trying to hide themselves behind the smoke-screen made by the destroyer. Still later we learned that the formation had turned back to the Skagerrak and was limping home at reduced speed.  A torpedo is loaded on a Beaufort of Coastal Command.  Bristol Beaufort torpedo-bombers set out.

Last edited by RedToo; 09/17/10 09:06 PM.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3100736 - 09/24/10 09:09 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

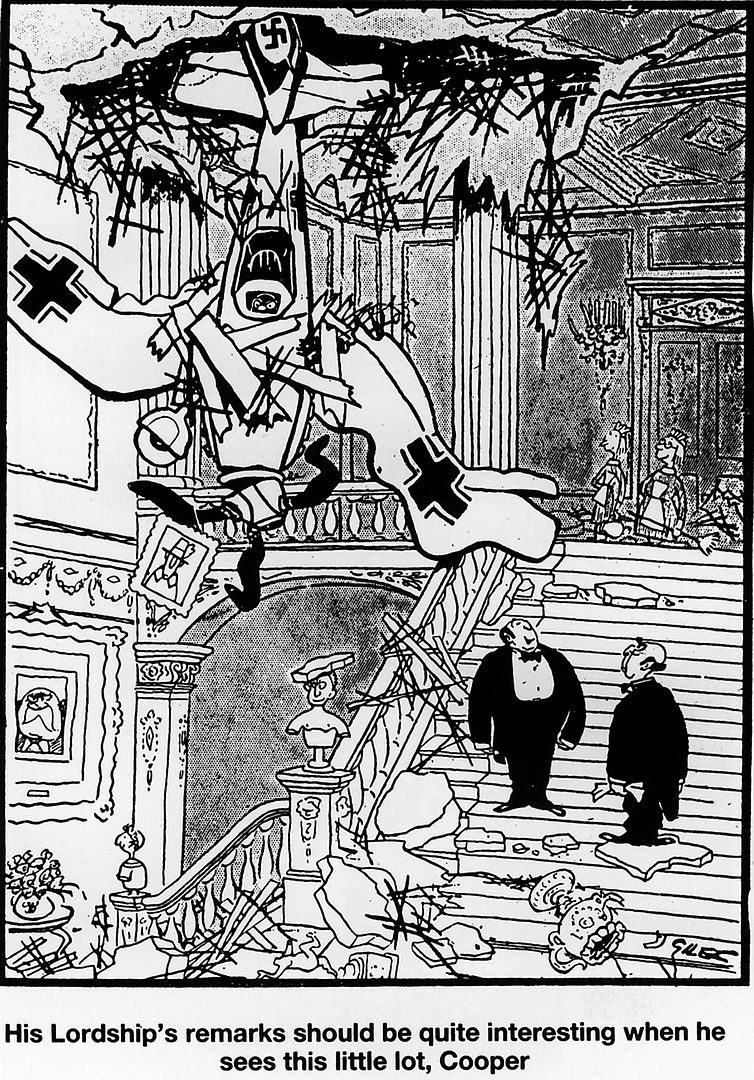

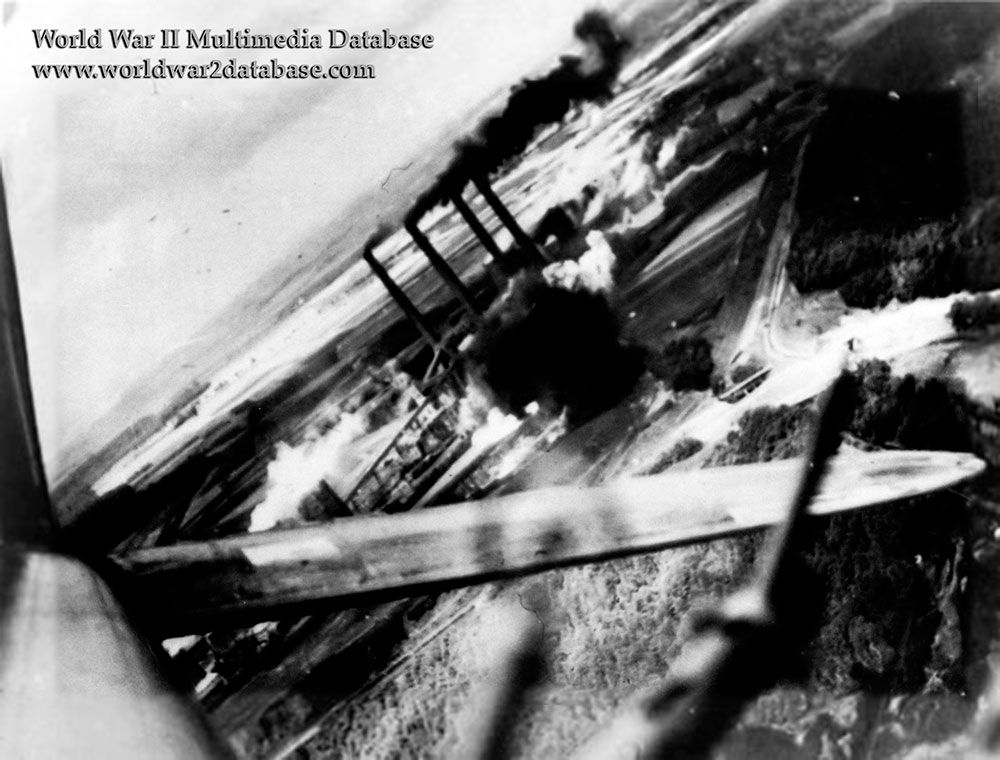

Part 80. 6. The Attack on Aalesund The harbour and anchorages of the Norwegian port of Aalesund�one of the bases from which Hitler supplies his Northern Russian front�were wreathed in smoke and flames for hours last night and this morning following the most devastating shipping attack ever carried out by a single squadron of the R.A.F. (Air Ministry Bulletin.) IT was still daylight when we set off over the North Sea, but darkness fell while we were on our way across. As we reached the Norwegian coast a bright moon was shining, which lit up the snow-covered mountains and countryside. We crossed an outer belt of small islands before coming to our target, which was shipping in the anchorage at Aalesund. In the anchorage itself there were several medium-sized ships at anchor. We were the second aircraft to arrive on the scene. The first arrival seemed to be drawing plenty of flak, while below him one of the ships was already burning furiously and dense clouds of smoke were drifting across the bay. My crew and I decided it would be best to float round for a time in order to find the best target and then choose the right moment for our attack. So we circled the bay, watching the other Hudsons doing their stuff. Several of them were attacking the ships from only a few feet above the sea, and it was most entertaining for us, at any rate, to watch the multi-coloured flak streaming down-wards at them from the hills around. But the guns didn't seem to be having much luck, and the only targets I could see them hitting were the ships they were supposed to protect. After one of these attacks I noticed a second ship starting to burn. Before long you could see a dull glow from its red-hot plates and then a mass of flames. At the same moment I saw a bomb burst alongside the large fish-oil factory in the harbour. In the meanwhile my crew and I were so fascinated by all, these interesting sights that we almost forgot about our own job. However, by now I had had plenty of opportunity of choosing my own particular target and to decide the best way to attack it. I had selected the biggest ship of the lot, and as it was still afloat, I thought I'd have a shot at dive-bombing her from a good height�especially as the flak was now concentrating entirely on the low-flying aircraft. So we climbed to about 6,000 feet and approached the target area from the sea. About five miles off Aalesund I throttled back, made a silent approach and, when we were almost directly over the ship, shoved my nose down, dropping a stick of heavy bombs right across her. The A.A. gunners must have been completely taken by surprise, as their guns didn't open up on us until we were well away. Then I circled the ship again to have a look at results. At first we saw nothing unusual and thought we'd missed her. But suddenly our Canadian gunner shouted over the inter�com. �I think I can see a glow from right inside the ship," and the next time we looked she was definitely down at the bows. A couple of minutes later the forecastle was well awash; then the water was up to her funnel and the rudder rose clear of the sea. I shouted to my crew, �Her boilers ought to burst any moment now," and sure enough a minute or two later there was a violent explosion amidships. Dense clouds of steam shot up into the air and in a very short while all we could see above the water was the flag flying from her stern, and that very soon disappeared. As we set course for home, fifteen minutes after we had dropped our bombs, all that remained were three boatloads of survivors rowing like hell for the shore. A couple of pics from the German side:  A Do 17 of IInd Gruppe of KG 76, fitted with a 20mm cannon in the nose for strafing ground targets.  Low level attacks could be a dangerous business. On 17 May 1940 this Do 17 of II./KG 76 was strafing a French road convoy when an ammunition truck exploded violently. The German bomber suffered extensive damage, but the pilot, Unteroffizer Otto Stephani, was able to make a normal landing at his base in Vogelsang. The Dornier never flew again.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3105395 - 10/01/10 07:22 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 81. 7. Sweeps Over France An Irish flight lieutenant who was recently awarded a second bar to his D.F.C. and who leads a flight of a famous Australian squadron shot down his 21st enemy aircraft to-day (Thursday), just a few days before his 21st birthday. (Air Ministry Bulletin.) I'VE been on about fifty sweeps, and most of my victories have been gained over France. I've got my bag because I've been blessed with a pair of good eyes, and have learned to shoot straight. I've not been shot down�touch wood� and I've only once been badly shot up (I hope that doesn't sound Irish). And for all that I've got a lot to thank the pilots in my section. They are Australians and I've never met a more loyal or gamer crowd of chaps. They've saved my bacon many a time when I've been attacked from behind while concentrating on a Messerschmitt in front of me, and they've followed me through thick and thin. On the ground they're the cheeriest friends a fellow could have. I'm sure that Australia must be a grand country if it's anything like its pilots, and after the war I'm going to see it. No, not flying, or farming. I like a job with figures�accountancy or auditing. Perhaps that doesn't sound much like a fighter pilot. But pilots are perfectly normal people. Before going off on a trip I usually have a funny feeling in my tummy, but once I'm in my aircraft everything is fine. The brain is working fast, and if the enemy is met it seems to work like a clockwork motor. Accepting that, rejecting that, sizing up this, and remembering that. You don't have time to feel anything. But your nerves may be on edge� not from fear, but from excitement and the intensity of the mental effort. I have come back from a sweep to find my shirt and tunic wet through with perspiration. Our chaps sometimes find that they can't sleep. What happens is this. You come back from a show and find it very hard to remember what happened. Maybe you have a clear impression of three or four incidents, which stand out like illuminated lantern slides in the mind's eye. Perhaps a picture of two Me. 109's belting down on your tail from out of the sun and already within firing range. Perhaps another picture of your cannon shells striking at the belly of an Me. and the aircraft spraying debris around. But for the life of you, you can't remember what you did. Later, when you have turned in and sleep is stealing over you, some tiny link in the forgotten chain of events comes back. Instantly you are fully awake, and then the whole Story of the operation pieces itself together and you lie there, sleep driven away, re-living the combat, congratulating your�self for this thing, blaming yourself for that. The reason for this is simply that everything happens so quickly in the air that you crowd a tremendous amount of thinking, action and emotion into a very short space of time, and you suffer afterwards from mental indigestion. The other week I was feeling a little jaded. Then my seven days' leave came round, and I went back bursting with energy. On my first flight after getting back I shot down three Me.'s in one engagement, and the next day bagged two more. That shows the value of a little rest. It's a grand life, and I know I'm lucky to be among the squadrons that are carrying out the sweeps. The tactical side of the game is quite fascinating. You get to learn, for instance, how to fly so that all the time you have a view behind you as well as in front. The first necessity in combat is to see the other chap before he sees you, or at least before he gets the tactical advantage of you. The second is to hit him when you fire. You mightn't have a second chance. After a dog-fight your section gets split up, and you must get together again, or tack on to others. The straggler is easy meat for a bunch of Jerries. Luckily, the chaps in my flight keep with me very well, and we owe a lot to it. On one occasion recently I saw an Me. dive on to one of my flight. As I went in after him, another Me. tailed in behind to attack me, but one of my flight went in after him. Soon half a dozen of us were flying at 400 m.p.h. in line astern, everybody, except the leader, firing at the chap in front of him. I got my Hun just as my nearest pal got the Hun on my tail, and we were then three Spitfires in the lead. When we turned to face the other Me.'s we found that several others had joined in, but as we faced them they turned and fled. The nearest I've been to being shot down was when another pilot and I attacked a Ju. 88. The bomber went down to sea level, so that we could only attack from above, in face of the fire of the Ju.'s rear guns. We put that Ju. into the sea all right, but I had to struggle home with my aircraft riddled with bullets and the undercarriage shot away. I force-landed without the undercarriage, and was none the worse for it. But it wasn't very nice at the time. Well, as I said just now, one day I'm planning to go to Australia�and audit books.  This He-111 crashed in the North East of England  Unteroffizier Karl Meier, a radio operator with I./StG 7. During the attack on Thorney Island his aircraft was attacked by British fighters. He suffered eight hits on his body from British machine-gun rounds, but escaped with only flesh wounds.

Last edited by RedToo; 10/01/10 07:23 PM.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3110610 - 10/08/10 08:01 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

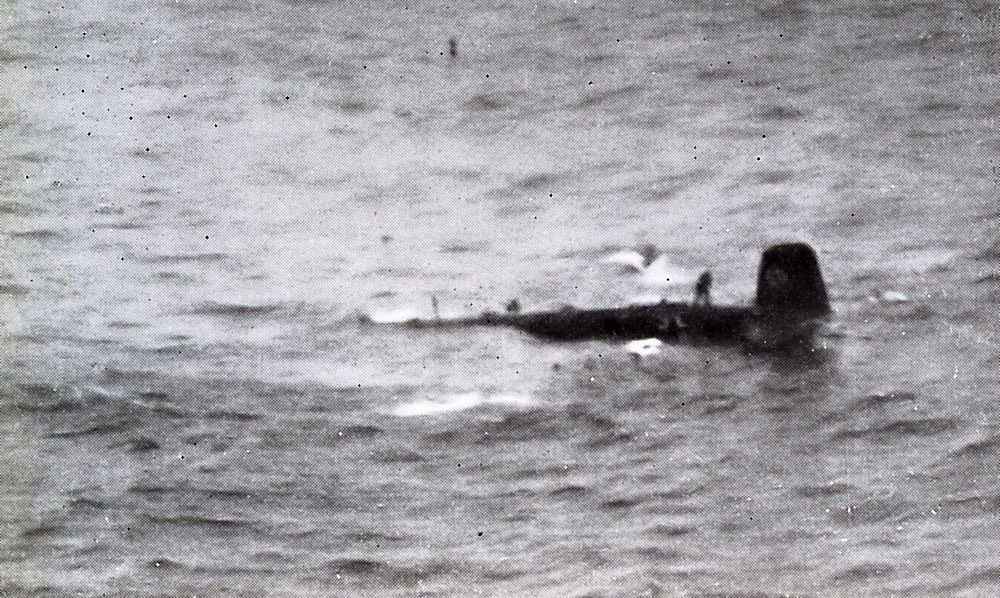

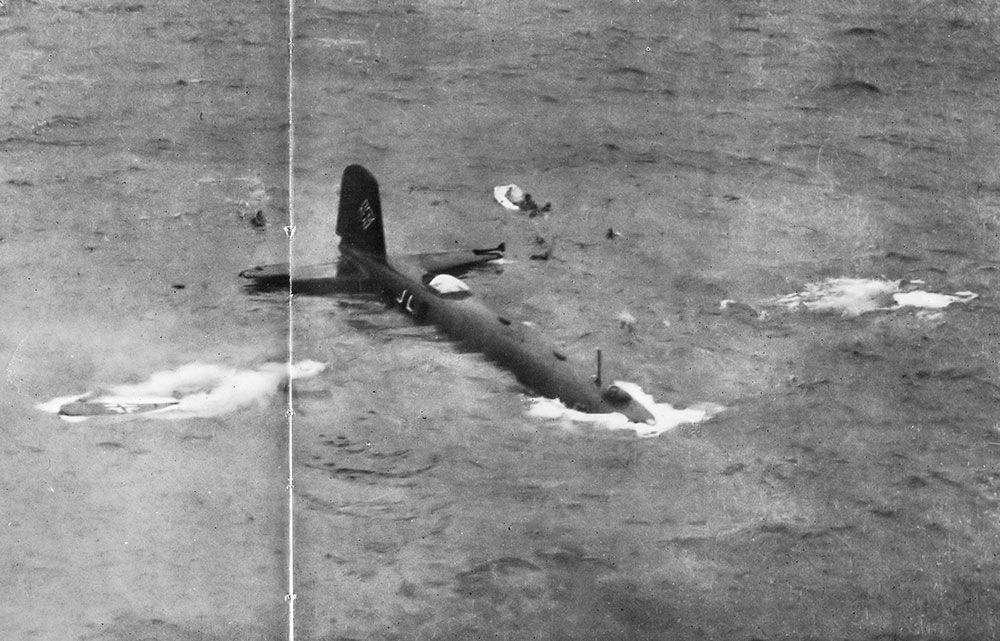

Part 82. 8. Condor Written Off A Focke-Wulf Condor, on the way to attack Atlantic convoys, was intercepted to-day by a Lockheed Hudson of the R.A.F. Coastal Command ... (Air Ministry Bulletin.) THE Focke-Wulf which we disposed of is by no means the first one to have been shot down in the Battle of the Atlantic. But this time it happens to have been written off by one of the Hudson squadrons which are now in action day and night over the wide battlefield of the Western Ocean. My crew and I have been on the job of escorting and pro�tecting convoys in the Atlantic for months past. It's largely monotonous work, helping to keep the shipping lanes safe�arduous and unspectacular work which has to be done mostly in wretched weather conditions so far as visibility is concerned. It is work that doesn't often come into the news. It's a real case of no news being good news. While the convoys are going through safely without molestation from the air or from surface raiders and U-boats, there is no news. All is well. But my crew and I were longing for some liveliness. The other day we got a real packet of it. It happened like this. Away out in the Atlantic, hours after dawn, we made our rendezvous with the convoy and the escorting warships. We did our usual stuff over them for more than a couple of hours, circling round and round in wide sweeps looking for possible danger. There wasn't a sign of anything in the air or on the sea. My relief was well on the way out and my fuel was getting a bit low, so I signalled �Good-bye and good luck" to the convoy. I was just setting course for home when something�I don't know what�told me to have a final look round. So I made another wide circuit of the ships. I was half-way round when one of the escorting warships spelt out a signal to me with its lamp. The message read, �Suspicious aircraft to starboard." We flew on for a bit and sighted an aircraft about four miles away. It was flying very low, just above the sea, and on a steady course towards the convoy, taking good advan�tage of the very low cloud over the Atlantic. It was just a dot at first�but obviously a big fellow. I went on to have a look at him. Just as a precaution, I pulled down my front gun sights, and mentioned to my co-pilot that I had the stranger beautifully in my sights. He suddenly let out an Irish yell. �Hi! It�s a blinking Condor!� he cried. He was jolly well right, too. It was a Focke-Wulf Condor painted sea-green as camouflage. The big German was going straight for the convoy and was now only two miles from it. The second pilot ran back to man the side gun of the Hudson. I went all out on the throttle and at 1,100 feet began to dive. Four hundred yards away I was wondering who would fire first. At that moment the German and I began firing simultaneously, but my front guns didn't seem to be doing him any damage. The enemy's shooting was bad. Not one of his bullets or cannon shells hit us then or afterwards. I brought my Hudson still lower and got into position 200 yards away to give my rear gunner a chance. He took it beautifully and promptly. I could see the tracer bullets from his tail gun whipping into the Focke-Wulf's two port engines and into its fuselage about mid-wing. We got closer still�actually to between 20 and 30 feet�so close that the Focke-Wulf looked like a house. All the time my tail-gunner's tracers were still ripping into the Jerry. When there was only 8 yards between us we saw a gun poked out from a window of the Focke-Wulf. A face appeared above it, but it wasn't there long. The second pilot saw the face and spoiled it with a burst from one of his side guns. By this time two of the four engines of the Focke-Wulf were in a glow. The German turned. As he did so he showed us his belly. My tail and side guns absolutely raked it. I made a tight turn the other way. When the Hudson came out of it, I saw the German about a mile away still flying apparently all right. We know that these big Focke-Wulfs are built to give and take heavy punishment. But I was amazed that this fellow could still fly at all after the hiding we had given him. I set off after him again, but the chase didn't last long. The Focke-Wulf soon crashed into the sea. It pancaked on the water, and we could see five members of its crew swimming from the wreckage and another one scampering along the fuselage. We went round them a few times until we saw the six survivors hanging on to a rubber dinghy. The last we heard was that they were picked up by one of our warships. We had a last look at the convoy. Every man on board the warships and merchant vessels, from captains to cooks, seemed to be on deck, waving and signalling their thanks for the grandstand view of the end of another Focke-Wulf. My relief was now in sight and so I made for home. Two pics of the same Condor in the Atlantic:

|

|

#3116324 - 10/15/10 07:21 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 83. 9. Night Fighter Of the 33 enemy raiders destroyed last night it is now established that four were brought down by A.A. guns. The remaining 29 fell to the guns of the R.A.F. night-fighter pilots�. Our night-fighting forces took full advantage of the brilliant moonlight. (Air Ministry Bulletin.) Try to imagine the moonlight sky, with a white back ground of snow nearly six miles below. Somewhere near the centre of a toy town a tiny flare is burning. Several enemy bombers have come over, but only one fire has gained a hold. After all the excitement of my two combats, I can still see that amazing picture of London clearly in my mind. It was indeed the kind of night that we fly-by-nights pray for. I had been up about three-quarters of an hour before I found an enemy aircraft. I had searched all round the sky when I suddenly saw him ahead of me. I pulled the boost control to get the highest possible speed and catch him up. I felt my Hurricane vibrate all over as she responded and gave her maximum power. I manoeuvred into position where I could see the enemy clearly with the least chance of his seeing me. As I caught him up I recognised him�a Dornier �flying pencil." Before I spotted him I had been almost petrified with the cold. I was beginning to wonder if I should ever be able to feel my hands, feet or limbs again. But the excitement warmed me up. He was now nearly within range and was climbing to 30,000 feet. I knew the big moment had come. I daren't take my eyes off him, but just to make sure that everything was all right I took a frantic glance round the " office "� that's what we call the cockpit�and checked everything. Then I began to close in on the Dormer and found I was travelling much too fast. I throttled back and slowed up just in time. We were frighteningly close. Then I swung up, took aim, and fired my eight guns. Almost at once I saw little flashes of fire dancing along the fuselage and centre section. My bullets had found their mark. I closed in again, when suddenly the bomber reared up in front of me. It was all I could do to avoid crashing into him. I heaved at the controls to prevent a collision, and in doing so I lost sight of him. I wondered if he was playing pussy and intending to jink away, come up on the other side and take a crack at me, or whether he was hard hit. The next moment I saw him going down below me with a smoke trail pouring out. Some of you may have seen that smoke trail. I felt a bit disappointed, because it looked as if my first shots had not been as effective as they appeared. Again I pulled the boost control and went down after him as fast as I knew how. I dived from 30,000 feet to 3,000 feet at such a speed that the bottom panel of the aircraft cracked, and as my ears were not used to such sudden changes of pressure I nearly lost the use of one of the drums. But there was no time to think of these things. I had to get that bomber. Then as I came nearer I saw he was on fire. Little flames were flickering around his fuselage and wings. Just as I closed in again he jinked away in a steep climbing turn. I was going too fast again, so I pulled the stick back and went up after him in a screaming left-hand climbing turn. When he got to the top of his climb I was almost on him. I took sight very carefully and gave the button a quick squeeze. Once more I saw little dancing lights on his fuselage, but almost instantaneously they were swallowed in a burst of flames. I saw him twist gently earthwards and there was a spurt of fire as he touched the earth. He blew up and set a copse blazing. I circled down to see if any of the crew had got out, and then I suddenly remembered the London balloon barrage, so I climbed up and set course for home. I had time now to think about the action. My windscreen was covered with oil, which made flying uncomfortable, and I had a nasty feeling that I might have lost bits of my aircraft. I remembered seeing bits of Jerry flying past me. There were several good-sized holes in the fabric, which could have been caused only by hefty lumps of Dornier. Also the engine seemed to be running a bit roughly, but that turned out to be my imagination. Anyway I soon landed, reported what had happened, had some refreshment, and then up in the air once more, southward ho ! for London. Soon after I was at 17,000 feet. It's a bit warmer there than at 30,000. I slowed down and searched the sky. The next tiling I knew, a Heinkel was sitting right on my tail. I was certain he had seen me, and wondered how long he had been trailing me. I opened my throttle, got round on his tail and crept up. When I was about 400 yards away he opened fire�and missed me. I checked my gadgets, then I closed up and snaked about so as to give him as difficult a target as possible. I got into a firing position, gave a quick burst of my guns and broke away. I came up again, and it looked as if my shots had had no effect. Before I could fire a second time, I saw his tracer bullets whizzing past me. I fired back and I knew at once that I had struck home. I saw a parachute open up on the port wing. One of the crew was baling out. He was quickly followed by another. The round white domes of the parachutes looked lovely in the moonlight. It was obvious now that the pilot would never get his aircraft home, and I, for my part, wanted this second machine to be a �certainty" and not a " probable." So I gave another quick burst of my guns. Then to fool him I attacked from different angles. There was no doubt now that he was going down. White smoke was coming from one engine, but he was not yet on fire. I delivered seven more attacks, spending all my ammunition. Both his engines smoked as he got lower and lower. I followed him down a long way and as he flew over a dark patch of water I lost sight of him. But I knew he had come down, and where he had come down�it was all confirmed later�and I returned to my base ready to tackle another one. But they told me all the Jerries had gone home. �Not all," I said, "two of them are here for keeps." Shooting practice for pilots of JG26 during the Battle of Britain:

Last edited by RedToo; 10/15/10 07:23 PM.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3121367 - 10/22/10 07:31 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 84. 10. Canada Hits the Target A Canadian sergeant�one of the first batch to arrive in this country under the empire training scheme�to-day sunk a German supply ship of about 2,500 tons with a direct bomb hit on the stern. (Air Ministry Bulletin.) WHEN I was training out in Canada we used to practise dropping small bombs on little wooden targets in Lake Ontario. And, of course, when we did so we all thought of the day when we would be dropping rather larger bombs on real targets with Germans in them. This thought didn't seem to improve my aim much, however, for try as hard as I could I never actually succeeded in scoring a direct hit on those little targets in Lake Ontario. But the day I used to think about over in Canada has now arrived, and I am going to give you an account of it. When we took off there weren't many clouds to give us cover, and as we got nearer to the Dutch coast the clouds grew fewer. We made our landfall and turned to fly along the coast towards the Hook. And there, about three miles out from the mouth of the river, we saw a German supply ship well down in the water as though she were carrying a heavy cargo. Because there was so little cloud cover, we were rather high up for bombing, but we decided to have a crack at it. " We'll make a run over, anyway," said the pilot, who incidentally is also a Canadian. I got down to the bomb-sight and started to adjust it for height and drift, while the pilot made almost a perfect run up. I only had to give him one correction in course. The ship, by the way, was firing at us by then with the gun on her bows, and several shore batteries were opening up, too. Black clouds of high explosive were forming a little way from us. The first time I saw them I didn't realise what was happening. �Those are funny looking clouds ahead of us," I said to the pilot. �Boy!� he replied, �those aren't clouds!� But to continue, I was adjusting my bomb-sight and everything seemed to fit in perfectly. Just as I got the final adjustments made the ship seemed to fall plump into the sights, so I released a single heavy bomb�the first bomb I had dropped over here. The ship swung round to take avoiding action and swung her stern right under the bomb. I saw it explode, a direct hit on the stern�which was more than I ever did to those little targets on Lake Ontario. The explosion was followed by a big cloud of black smoke. I found myself shouting with excitement. The gunner too was singing out, �It�s a hit�it's a hit!" The pilot said, �I do think you might have dropped it down her funnel." Then there was another explosion on the ship, with a cloud of white steam this time. Her boilers had burst. I know what that looks like, because I once saw a ship's boilers burst on the Canadian lakes when I was working as a steward on an excursion steamer in the summer, to pay my way through college in the Fall. We did not have much time to enjoy our excitement, because just then the gunner called out a warning that there were two Messerschmitts coming. I looked down, and there they were, streaking up at us. So we climbed into some cloud and flew around until we figured we'd lost them. But, just before we went into the cloud, the gunner saw that the ship was sinking rapidly by the stern. Then we flew back to our base in England�and I had dropped my first bomb.  This HE-111 H1 coded IH+EN of II./ Kampfgeschwader 26 force-landed on the 9th of February 1940 near Dalkeith in Midlothian, after combat with a Spitfire I of 602 (City of Glasgow) Squadron. It was repaired, given RAF roundels and the serial AW177, and used for testing purposes.  The cockpit of a Messerschmitt Bf 110 from the radio operator/ rear gunners position, November 1940.

Last edited by RedToo; 10/22/10 07:32 PM. Reason: Typo.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3126648 - 10/29/10 07:16 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 85. 11. Starboard Wing on Fire. The king has been graciously pleased to confer the Victoria Cross on the undermentioned airman in recognition of most conspicuous bravery: NZ/401793 Sergeant -------- Royal New Zealand Air Force-No. 75 (N.Z.) Squadron. On the night of 7th July, 1941, Sergeant --------- was second pilot of a Wellington returning from an attack on Munster. . . . (Air Ministry Bulletin.) It was on one of the Munster raids that it happened. It had been one of those trips that you dream about�hardly any opposition over the target; just a few searchlights but very little flak�and that night at Munster I saw more fires than I had ever seen before. We dropped our bombs right in the target area and then made a circuit of the town to see what was going on before the pilot set course for home. As second pilot I was in the astro-dome keeping a look-out all round. All of a sudden, over the middle of the Zuider Zee, I saw an enemy machine coming in from port. I called up the pilot to tell him, but our inter-com. had gone phut. A few seconds later, before anything could be done about it, there was a slamming alongside us and chunks of red-hot shrapnel were shooting about all over the place. As soon as we were attacked, the squadron leader who was flying the plane put the nose down to try and dive clear. At that time we didn't know that the rear gunner had got the attacking plane, a Messerschmitt 110, because the inter-com. was still out of action and we couldn't talk to the rear turret. We'd been pretty badly damaged in the attack. The starboard engine had been hit and the hydraulic system had been put out of action, with the result that the undercarriage fell half down, which meant, of course, that it would be useless for landing unless we could get it right down and locked. The bomb doors fell open too, the wireless sets were not working, and the front gunner was wounded in the foot. Worst of all, fire was burning up through the upper surface of the starboard wing where a petrol feed pipe had been split open. We all thought we'd have to bale out, so we put on our parachutes. Some of us got going with the fire extinguisher, bursting a hole in the side of the fuselage so that we could get at the wing, but the fire was too far out along the wing for that to be any good. Then we tried throwing coffee from our flasks at it, but that didn't work either. It might have damped the fabric round the fire, but it didn't put the fire out. By this time we had reached the Dutch coast and were flying along parallel with it, waiting to see how the fire was going to develop. The squadron leader said, �What does it look like to you?� I told him the fire didn't seem to be gaining at all and that it seemed to be quite steady. He said, �I think we'd prefer a night in the dinghy in the North Sea to ending up in a German prison camp." With that he turned out seawards and headed for England. I had a good look at the fire and I thought there was a sporting chance of reaching it by getting out through the astro-dome, then down the side of the fuselage and out on to the wing. Joe, the navigator, said he thought it was crazy. There was a rope there; just the normal length of rope attached to the rubber dinghy to stop it drifting away from the aircraft when it's released on the water. We tied that round my chest, and I climbed up through the astrodome. I still had my parachute on. I wanted to take it off because I thought it would get in the way, but they wouldn't let me. I sat on the edge of the astro-dome for a bit with my legs still inside, working out how I was going to do it. Then I reached out with one foot and kicked a hole in the fabric so that I could get my foot into the framework of the plane, and then I punched another hole through the fabric in front of me to get a hand-hold, after which I made further holes and went down the side of the fuselage on to the wing. Joe was holding on to the rope so that I wouldn't sort of drop straight off. I went out three or four feet along the wing. The fire was burning up through the wing rather like a big gas jet, and it was blowing back just past my shoulder. I had only one hand to work with getting out, because I was holding on with the other to the cockpit cover. I never realised before how bulky a cockpit cover was. The wind kept catching it and several times nearly blew it away and me with it. I kept bunching it under my arm. Then out it would blow again. All the time, of course, I was lying as flat as I could on the wing, but I couldn't get right down close because of the parachute in front of me on my chest. The wind kept lifting me off the wing. Once it slapped me back on to the fuselage again, but I managed to hang on. The slipstream from the engine made things worse. It was like being in a terrific gale, only much worse than any gale I've ever known in my life. I can't explain it, but there was no sort of real sensation of danger out there at all. It was just a matter of doing one thing after another and that's about all there was to it. I tried stuffing the cockpit cover down through the hole in the wing on to the pipe where the fire was starting from, but as soon as I took my hand away the terrific draught blew it out again and finally it blew away altogether. The rear gunner told me afterwards that he saw it go sailing past his turret. I just couldn't hold on to it any longer. After that there was nothing to do but to get back again. I worked my way back along the wing, and managed to haul myself up on to the top of the fuselage and got to sitting on the edge of the astro-dome again. Joe kept the dinghy rope taut all the time, and that helped. By the time I got back I was absolutely done in. I got partly back into the astro-hatch, but I just couldn't get my right foot inside. I just sort of sat there looking at it until Joe reached out and pulled it in for me. After that, when I got inside, I just fell straight on to the bunk and stayed there for a time. . . . Just when we were within reach of the English coast the fire on the wing suddenly blazed up again. What had happened was that some petrol which had formed a pool inside the lower surface of the wing had caught fire. I remember thinking to myself, �This is pretty hard after having got as far as this." However, after this final flare-up the fire died right out�much to our relief, I can tell you. The trouble now was to get down. We pumped the wheels down with the emergency gear and the pilot decided that, instead of going to our own base, he'd try to land at another aerodrome nearby which had a far greater landing space. As we circled before landing he called up the control and said, �We�ve been badly shot up. I hope we shan't mess up your flare-path too badly when we land." He put the aircraft down beautifully, but we ended up by running into a barbed-wire entanglement. Fortunately nobody was hurt though, and that was the end of the trip. NZ/401793 was Sergeant James Edward Allen Ward. He was killed on operations on the 15th of September 1941.  More can be found here: http://www.birkenheadrsa.com/vc-james-ward.htmlhttp://www.victoriacross.org.uk/bbwardja.htmhttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Allen_Ward

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3131488 - 11/05/10 05:41 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

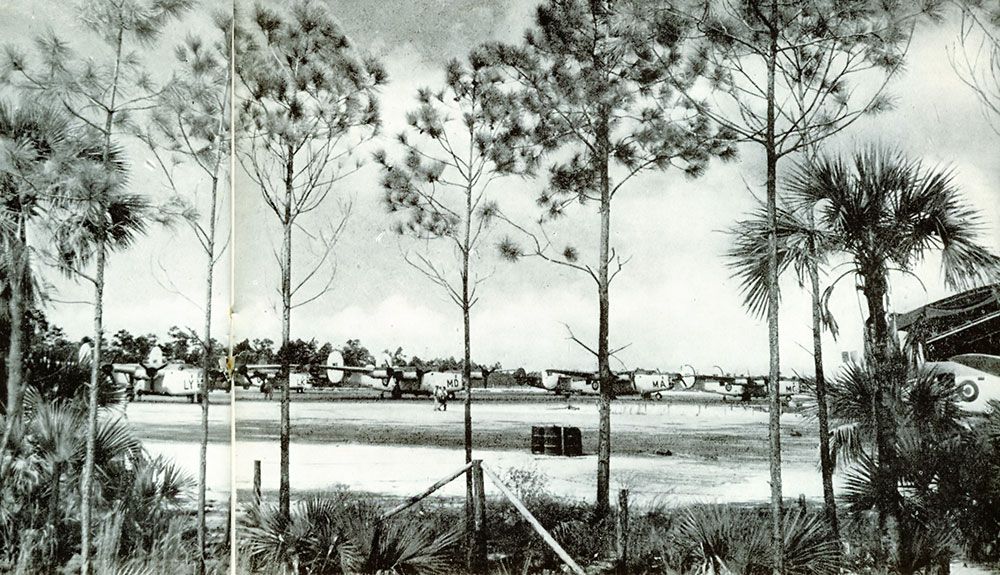

Part 86. 12. Havoc Stalks Hun Fighter command pilots in American-built Havoc aircraft paid visits to German-occupied aerodromes in northern France during the night. (Air Ministry Bulletin.) First of all, I should like to tell you not to measure the value of this night-fighter work over German aerodromes by the number of enemy aircraft known to have been destroyed. This is considerable, but I know positively that our mere presence over the enemy's bases has caused the loss of German bombers without even a shot being fired at them. Moreover, our presence upsets the Luftwaffe bomber organisation, throws their plans out of gear in many ways, and has a very big effect on the morale of the bomber crews. Night-fighter pilots chosen for this work are generally of a different type to the ordinary fighter pilot. They must like night-fighting to begin with, which is not everybody's meat. They must also have the technique for blind flying, and when it comes to fighting, must use their own initiative and judgment, since they are cut off from all communications with their base and are left as free lances entirely to their own resources. Personally I love it. Once up, setting a course in the dark for enemy-occupied country, one gets a tremendous feeling of detachment from the world. And when the enemy's air base is reached there is no thrill�even in big-game shooting �quite the same. On goes the flare-path, a bomber comes low�making a circuit of the landing field�lights on and throttle shut. A mile or two away, in our stalking Havoc, we feel our hearts dance. The throttle is banged open, the stick thrust forward, and the Havoc is tearing down in an irresistible rush. One short burst from the guns is usually sufficient. The bomber's glide turns to a dive�the last dive it is likely to make. Whether you get the Hun or miss him, he frequently piles up on the ground through making his landing in fright. My own successes stand out clearly in my mind. There was one night over France when I got an He. 111 for sure, and a Ju. 88 as a probable. It was the night of the last big raid on London, and the Huns were streaming back to their bases in swarms. I got a crack at the Ju. as, with navigation lights on, it came down to land. The bullets appeared to enter the starboard engine and fuselage of the bomber. My onward rush carried us, over the Ju., some ten feet above it, and as we passed my rear gunner poured a longish burst into the port engine. The bomber went into an almost vertical dive. She was only 800 feet up, and it is practically impossible that the pilot could have pulled out of the dive, apart from the fact that both his engines were damaged. But we only claimed the Ju. as a probable. After this, all the aerodrome lights were turned off. We climbed away and the lights came on again. So we bombed the aerodrome, and large fires resulted. The aerodrome lights were again put out. But there were numerous bombers still trying to land. We came down to 1,000 feet again and met an He. 111. I opened fire close in. The bullets entered one engine and the fuselage. After a second burst smoke poured from both engines, and it went into a steep, side-slipping turn. As we passed beneath her, the gunner put in another burst. Then, one night near St. Leger, after we had bombed the aerodrome at Douai, we met a huge Focke-Wulf Condor, a four-engined transport. It had its navigation lights on, about to land. At only 50 yards range, I put a good burst into the transport's belly. It was all that was necessary. The Condor gave out an enormous flash of light, burst into flames and blew to bits. Burning debris flew past my aircraft on all sides. When the Condor exploded in front of us, the flash was so blinding and the force was so great that we all thought our own machine had exploded. My most recent thrill was a fortnight ago, when I got one enemy aircraft destroyed and damaged two others, over an aerodrome which I visited by chance. I happened to go that way, and was overjoyed to find myself there at the right moment. Only a few aircraft were operating that night from that vicinity, and I was able to have a crack at three of them. Extra info. about the pilot in the above account provided by mhuxt from the twin thread to this over at UBI: The pilot is Bertie Rex O'Bryen Hoare, of 23 Squadron. The date should have told me - the only Havoc Intruder squadron during the time of large raids on London was 23. He claimed a Ju 88 Probably Destroyed and an He 111 Destroyed at Le Bourget on 3/4 May 1941, and claimed damage to an unidentified four-engine aircraft, believed to have been an Fw 200, on 21/22 April 1941 at St. Leger airfield (actually while flying a Blenheim). Hoare was a most interesting character. A pre-war pilot, he flew throughout the conflict with one good and one glass eye, having had a duck crash through his windscreen in a flying accident in the 30s. Poor fellow was eventually lost after the war, flying a Mosquito to Singapore. He crash-landed on a small island during bad weather, and was badly injured. Rescuers eventually found him, but too late. Thanks mhuxt.  A Havoc night fighter-bomber makes ready to take off.  Bombing-up a Havoc night fighter-bomber.

Last edited by RedToo; 11/12/10 08:29 PM. Reason: Added extra info.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3136176 - 11/12/10 08:18 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

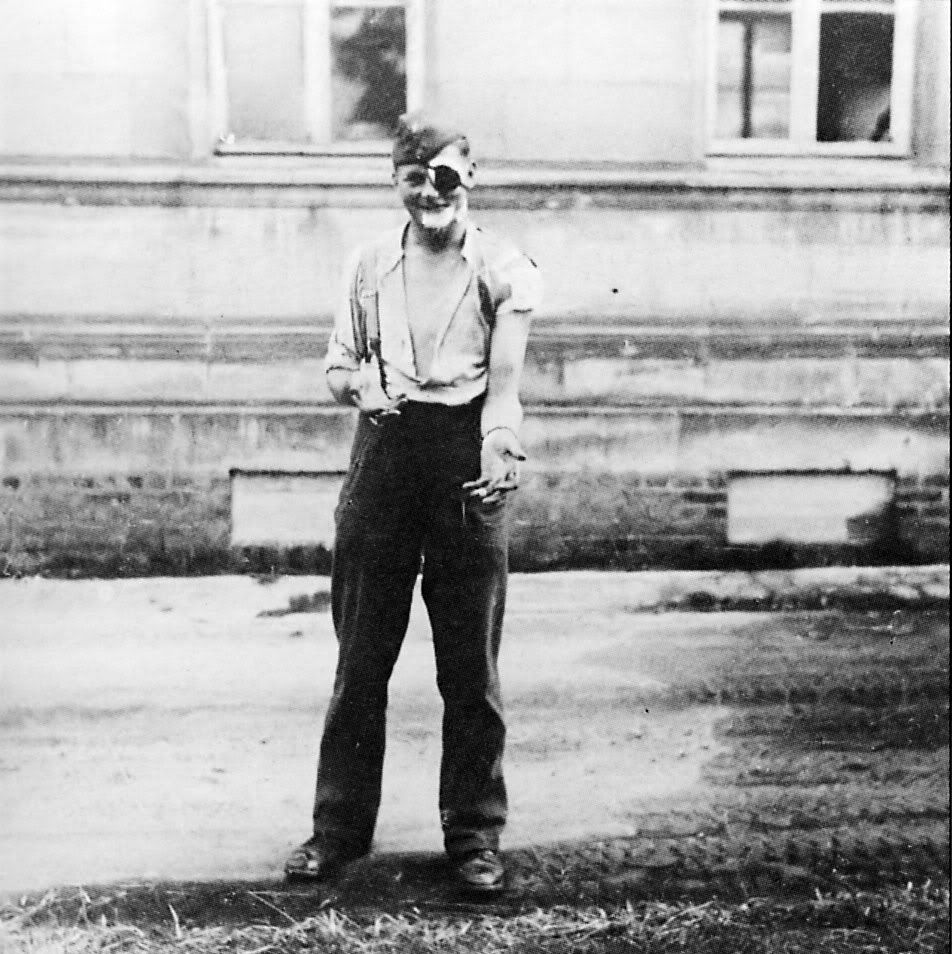

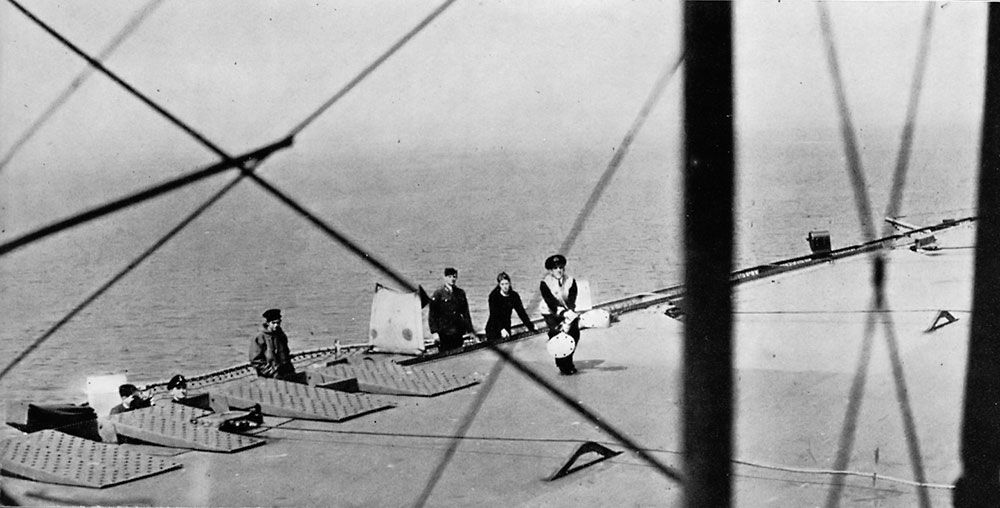

Part 87. 13. We Shadowed the "Bismarck" The following signals have been exchanged in connection with the "Bismarck'' operations between the admiralty and the A.O.C.-in-C, Coastal Command. From Admiralty to the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Coastal Command: Admiralty wish gratefully to acknowledge the part played by the reconnaissance of the forces under your command, which contributed in a large measure to the successful outcome of the recent operation. Message in reply to the above. To Admiralty from the A.O.C.-in-C, Coastal Command: Your message very much appreciated and has been repeated to all concerned. It was a great hunt and we are eager and ready for more. (Air Ministry Bulletin.) WE left our base at 3.30 in the morning, and we got to the area we had to search at 9.45. It was a hazy morning with poor visibility, and our job was to contact with �Bismarck," which had been lost since early Sunday morning. About an hour later we saw a dark shape ahead in the mist. We were flying low at the time. I and the second pilot were sitting side by side and we saw the ship at the same time. At first we could hardly believe our eyes. I believe we both shouted �There she is," or something of the sort. There was a forty-knot wind blowing and a heavy sea running, and she was digging her nose right in, throwing it white over her bows. At first, as we weren't sure that it was an enemy battleship, we had to make certain. So we altered course, went up to about 1,500 feet into a cloud, and circled. We thought we were near the stern of her when the cloud ended, and there we were, right above her. The first we knew of it was a couple of puffs of smoke just outside the cockpit window, and a devil of a lot of noise. And then we were surrounded by dark brownish black smoke as she pooped off at us with everything she'd got. She'd only been supposed to have eight anti-aircraft guns, but fire was coming from more than eight places�in fact, she looked just one big flash. The explosions threw the flying-boat about, and we could hear bits of shrapnel hit the hull. Luckily only a few penetrated. My first thought was that they were going to get us before we'd sent the signal off, so I grabbed a bit of paper and wrote out the message and gave it to the wireless operator. At the same time the second pilot took control, and took avoiding action. I should say that as soon as the �Bismarck �saw us she'd taken avoiding action too, by turning at right angles, heeling over and pitching in the heavy sea. When we'd got away a bit we cruised round while we inspected our damage. The rigger and I went over the aircraft, taking up floor-boards and thoroughly inspecting the hull. There were about half a dozen holes, and the rigger stopped them up with rubber plugs. We also kept an eye on the petrol gauges, because if they were going down too fast, that meant the tanks were holed and we wouldn't stand much chance of getting home. However, they were all right, and we went back to shadow �Bismarck." Then we met another Catalina. She'd been searching an area north of us, when she intercepted our signals and closed. On the way she'd seen a naval force, also coming towards us at full pelt through the heavy seas. They were part of our pursuing Fleet. When we saw this Catalina we knew she was shadowing the ship from signals we'd intercepted and because she was going round in big circles. So I formated on him and went close alongside. I could see the pilot through the cockpit window and he pointed in the direction the �Bismarck" was going. He had come to relieve us: it was just as well, for we couldn't stay much longer, because the holes in our hull made it essential to land in daylight. So we left the other Catalina to shadow �Bismarck." You all know what happened after that. We landed just after half-past nine at night, after flying for over eighteen hours. But one of our Catalinas during this operation set up a new record for Coastal Command of twenty-seven hours on continuous reconnaissance.  Consolidated Catalina Flying Boat. Two Pratt and Whitney twin Wasp engines each developing 1,200 h.p. Range over 4,000 miles. The water looks almost as good as Oleg�s �  Bombing-up is a skilled and delicate process. More info: one of the crew of the Catalina was an American. Thanks to mhuxt for pointing me towards this. Ensign Leonard B. "Tuck" Smith was acting as co-pilot to Flying Officer Dennis Briggs on the Catalina that found the Bismarck. He was one of a group of American pilots sent over to the UK to help train RAF pilots on the Catalina. This was well before America entered the war. The pic below shows Flying Officer Dennis Briggs at the microphone - perhaps recording the BBC talk above.  Flying Officer Dennis Briggs, pilot of the Consolidated PBY-5 (Catalina) flying boat that re-discovered the Bismarck on 26 May.

Last edited by RedToo; 11/13/10 07:24 PM. Reason: More info.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3140748 - 11/19/10 08:42 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 88. 14. W. A. A. F. in Air Raids It is now commonplace to hear that in German attacks on R.A.F. aerodromes the W.A.A.F. personnel displayed great courage and coolness. . . . (Air Ministry Bulletin.) ONE cool, sunny morning I was talking to my senior sergeant (flight-sergeant) in the guard-room about the ordinary routine of the day, when the station broadcast ordered one squadron "to come to readiness." I told her that I might as well stay where I was for the time being, and go with her down one of the airwomen's trenches nearby should there prove to be a raid. But as the minutes passed and there were no further announcements, I started off towards my office in the station headquarters building. As I entered headquarters the sirens wailed and we were told to go to the trenches. A few seconds later we heard one squadron roar into the air, then another, then still another, and finally the civilian air-raid warnings sounded in the surrounding country. We laughed and chatted on our way to the trenches, as this was no unusual occurrence. We had hardly settled down when the noise of the patrol�ling aircraft overhead changed from a constant buzz to the zoom and groan of aircraft in a dog-fight. Then aircraft and machine-guns barked and sputtered, while plane after plane dove down, with a head-splitting, nerve-shattering roar. I had no idea that so much could happen so quickly and remember thinking: " I suppose one feels like this in a bad earthquake." Then there was a lull, broken only by the sound of our aircraft returning to refuel and re-arm. A moment later a messenger arrived to report that a trench had been hit on the edge of the aerodrome. The padre and another officer followed the messenger to the scene of the disaster, and I thought I'd better go and see if the airwomen were all right in their trenches. All was now deathly silent. I climbed through debris and round craters back towards the W.A.A.F. guard-room. As I drew nearer, there was a strong smell of escaping gas. The mains had been hit. Another bomb had fallen on the airwomen's trench near the guard-room, burying the women who were sheltering inside. After a while I returned to headquarters to report to the Station Commander, and was told that the W.A.A.F. Officers' Mess could not be used as there was a delayed-action bomb in the garden. After some food, I went over to the W.A.A.F. cookhouse to see how things were going. The airwomen's Mess was the only one which had not been damaged by the raid, and I could see that they would have to do all the cooking for the station for a bit. On the way there I saw something like a white pillow lying on the ground. As I approached to pick it up a voice said out of the darkness, "I shouldn't touch that if I was you, Miss, it's marking a delayed-action bomb." I thanked him very much, and trying hard not to look as though I was walking any quicker than I had been previously, I proceeded on my way to the cookhouse. The airwomen were cooking virtually in the dark. But to their eternal credit they were producing delicious smelling sausages and mash to an endless stream of men going past a service hatch. The next afternoon, as I was returning to the aerodrome from my "billet-hunting " expedition with another W.A.A.F. officer, we were caught in a second attack. Our choices of action were few. There was no time to get to a trench, so we hurriedly put on our tin hats and ran into a nearby wood. As we did so, all the preliminary noises of the previous day began again. The edge of the wood was near a cross-roads, and as we ducked under the trees the police "bell-shelter " opened and a policeman shouted, " You'd better come in here." We did not hesitate, but scrambled in quickly. It was a tight squeeze, but it became much worse when a bus-driver, who also wanted admission, banged on the door. Somehow�I still don't know how�we got him inside. We waited till the noise had died down before we emerged, weighing, I am sure, much less. By the time we reached the aerodrome a fierce fire was raging in one quarter, but this time all my airwomen had escaped injury. This story covers a period of almost forty-eight hours. It started with a clean, tidy station, efficient to perfection; it ends with buildings destroyed, telephone lines blown up, and the aerodrome itself cratered. But not for one second did this station cease to be operational: it never failed to keep open its communications, and it still got fed! For their heroic work three of my airwomen were later awarded Military Medals.  WAAFs and airmen in the front line at the Chain Home Station above Ventnor on the Isle of Wight.  Across the road from Biggin Hill airfield, in the area that formerly housed the RAF married quarters, are roads named after the three WAAFs who won the Military Medal in the Battle of Britain. The date is that on which the award was gazetted.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3144945 - 11/26/10 08:30 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

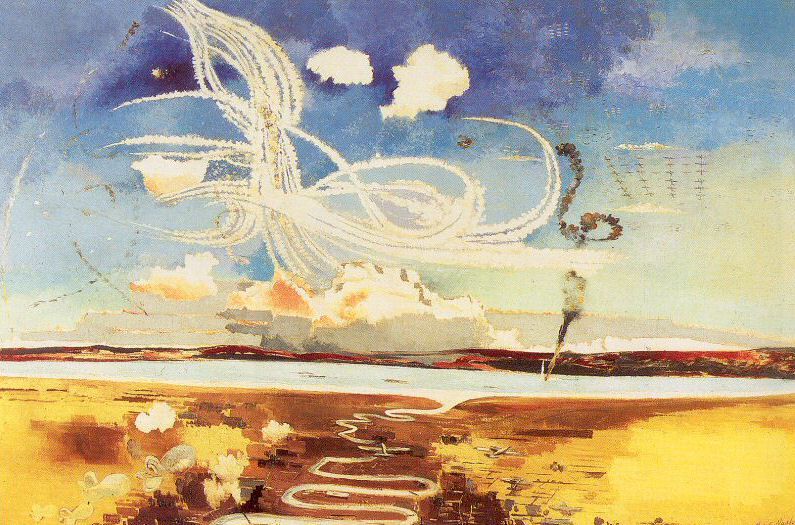

Part 89. 15. Dog-fights Over England The king has been graciously pleased to approve the following awards in recognition of gallantry displayed in flying operations against the enemy: Bar to the Distinguished Flying Cross. Acting Wing Commander --------, D.S.O., D.F.C. This fearless pilot has recently added a further four enemy aircraft to his previous successes; in addition, he has probably destroyed another four and damaged five hostile aircraft. . . . (Air Ministry Bulletin.) I'D like to tell you something about the boys in my squadron. They're grand lads, every one of them. About 75 per cent, are Canadians and many of them came over to this country a year or two before the war to join the R.A.F. Several worked their way across, at least two of them on cattle-boats, and they all came here to do what they'd wanted to do since they were youngsters�to fly. Since the war started they've shown that they can fight as well as they fly, and between them they've already won six of the nine D.F.C.s which have been awarded to the squadron. One holder of the D.F.C. is from Victoria, British Columbia. Another, who has won a bar to his D.F.C., comes from Calgary, Alberta. Others come from Toronto, Vancouver and Saskatoon. There's never been a happier or more determined crowd of fighter pilots, and, as an Englishman, I'm very proud to have the honour of leading them. I shan't soon forget the first time the squadron was in action under my leadership. It was on August 30th, and I detailed the pilot from Calgary to take his section of three Hurricanes up to keep thirty Me. 110's busy. "O.K., O.K.," he said with obvious relish, and away he streaked to deal with that vastly superior number of enemy fighters. When I saw him afterwards, his most vivid impression was of one German aircraft which he had sent crashing into a green-house. But perhaps I'd better start at the beginning of that particular day's battle. Thirteen of the squadron were on patrol near London. We were looking for the Germans whom we knew were about in large formations. Soon we spotted one large formation, and it was rather an awe-inspiring sight�particularly to anyone who hadn't previously been in action. I counted fourteen blocks of six aircraft�all bombers�with thirty Me. 110 fighters behind and above. So that altogether there were more than 100 enemy aircraft to deal with. Four of the boys had gone off to check up on some unidentified aircraft which had appeared shortly before we sighted the big formation, and they weren't back in time to join in the fun. That left nine of us to tackle the big enemy formation. I sent three Hurricanes up to keep the no's busy, while the remaining six of us tackled the bombers. They were flying at 15,000 feet with the middle of the formation roughly over Enfield, heading east. When we first sighted them they looked just like a vast swarm of bees. With the sun at our backs and the advantage of greater height, conditions were ideal for a surprise attack and as soon as we were all in position we went straight down on to them. We didn't adopt any set rule in attacking them�we just worked on the axiom that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. I led the attack and went for what I think was the third block of six from the back. And did those Huns break up ! In a few seconds there was utter confusion. They broke up all over the sky. As I went through, the section I aimed at fanned out. I can't give you an exact sequence of events, but I know that the Canadian pilot who followed immediately behind took the one that broke away to the left, while I took the one that broke away to the right. The third man in our line went straight through and gave the rear gunner of a Hun in one of the middle blocks an awful shock. Then the other boys followed on and things really began to get moving. Now there's one curious thing about this air fighting. One minute you see hundreds of aeroplanes in the sky, and the next minute there's nothing. All you can do is to look through your sights at your particular target�and look in your mirror too, if you are sensible, for any Messerschmitts which might be trying to get on to your tail. Well, that particular battle lasted about five or ten minutes, and then, quite suddenly, the sky was clear of aircraft. We hadn't shot them all down, of course; they hadn't waited for that, but had made off home in all directions at high speed. When we got down we totted up the score. We had destroyed twelve enemy aircraft with our nine Hurricanes. And when we examined our aircraft there wasn't a single bullet-hole in any of them! One pilot had sent a Hun bomber crashing into a green�house. Another bomber had gone headlong into a field filled with derelict motor-cars. It hit one of the cars, turned over and caught fire. Another of our chaps had seen a twin-engined job of sorts go into a reservoir near Enfield. Yet another pilot saw his victim go down with his engine flat out. The plane dived into a field and disintegrated into little pieces. Incidentally, that particular pilot brought down three Huns that day. Apart from our bag of twelve, there were a number of others which were badly shot up and probably never got home, like one which went staggering out over Southend with one engine out of action. Another day we like to remember�what fighter squadron who was in the show doesn't!�was Sunday, September 15th. when 185 enemy aircraft were destroyed. Our squadron led a wing of four or five squadrons in two sorties that day, and we emerged with 52 victims for the Wing, twelve of them falling to our squadron. On the first show that day we were at 20,000 feet, and ran into a large block of Ju. 88's and Do. 17's�about forty in all and without a single fighter to escort them. This time, for a change, we outnumbered the Hun, and believe me, no more than eight got home from that party. At one time you could see planes going down on fire all over the place, and the sky seemed full of parachutes. It was sudden death that morning, for our fighters shot them to blazes. One unfortunate German rear-gunner baled out of the Dornier 17 I attacked, but his parachute caught on the tail. There he was, swinging helplessly, with the aircraft swooping and diving and staggering all over the sky, being pulled about by the man hanging by his parachute from the tail. That bomber went crashing into the Thames Estuary, with the swinging gunner still there. Just about the same time one of my boys saw a similar thing in another Dornier, though this time the gunner who tried to bale out had his parachute caught before it opened. It caught in the hood, and our pilot saw the other two members of the crew crawl up and struggle to set him free. He was swinging from his packed parachute until they pushed him clear. Then they jumped off after him, and their plane went into the water with a terrific smack. I've always thought it was a pretty stout effort on the part of those two Huns who refused to leave their pal fastened to the doomed aircraft. The other day I led two of the latest recruits to the squadron on a search for a Ju. 88 off the East Coast. We found it fifty or sixty miles out to sea, and I led an attack from below. Suddenly the raider jettisoned his bombs and two of us had to duck out of the way. We know some of the German tricks to try to get rid of our fighters, and at first I thought he was throwing out some new kind of secret weapon to bump us off. Then I realised he'd let them go to help his speed. I kept with him and told the other two boys to go in and have a crack. Their shooting was amazingly accurate, and for the first time I saw bullets other than my own going into the fuselage of an enemy bomber. You know how the lights flash on a penny-in-the-slot bagatelle table ? As the little ball goes through the various pins different lights flash. Well, that's how the bullets from one of these Hurricanes went in. I watched them cracking in. The bomber pilot tried to get away and made for a cloud about the size of a man's hand. He went in, while one of my boys cruised around on top and the other waited underneath. Either the pilot of that Ju. 88 was a damned fool or he just couldn't help it, but he came flying nicely out of the cloud at the other end on a straight course. The boy on top nipped down on him like a greyhound after a hare. The boy below went up�it was almost like watching an event at a coursing meeting. When they had finished their ammunition those two Canadians left the bomber in a pretty bad state, and all I had to do was to finish him off.  The Battle of Britain by Paul Nash. Painted in 1941. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Nash_%28artist%29

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3149298 - 12/03/10 09:05 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|