|

#3003962 - 04/30/10 05:59 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 59. December, 1940 RAID ON TURIN BY A FLYING OFFICER THIS was the first time our squadron had done the Italian trip. We'd heard a rumour about a week before that we might be getting the job and everyone was quite thrilled at the idea of the run over the Alps. We were told in the morning that we were going to Turin and so we started at once drawing our tracks and getting the navigation generally weighed up. My navigator was particularly keen on the show because he's something of a mountaineer and has done a fair bit of climbing in the Alps. The route we were taking worked out at between twelve and thirteen hundred miles there and back. We had to make a bit of a detour to keep clear of Switzerland because we had special instructions to avoid infringing Swiss neutrality. Briefing was at two o'clock in the afternoon and we took off just as it was getting dark. To start with, the weather was poor and we had to come down to six hundred feet over the English coast to pinpoint ourselves, then we climbed up through what was becoming really nasty weather, and crossed the coast on the other side fairly high. By that time the cloud was what we call ten-tenths�that's to say, it obscured everything, but eventually we got above cloud and then we had the light of the moon which was in its first quarter. Before that it had been very dark indeed. We were flying blind above cloud until we arrived forty or fifty miles east of Paris and then we ran into clearer weather, the clouds gradually decreased below us until we could see the ground, and when we reached southern France the weather was perfect. It was one of those clear moonlight nights when the stars seem to stand out in the sky and you feel you can put out your hand and grab one. As we flew on towards the Alps, we could make out some of the little mountain villages against a background of snow, the whole scene resembled a picture on a Christmas card. The aircraft was going wonderfully well and we cleared the highest mountains we went over by three or four thousand feet. You could see the ridges and peaks, well defined, and the moon shining on the snow was half turning the night into day. Flying over this sort of scenery was something completely new to us and pretty awe-inspiring. The nearest we'd got to it was on the Munich raid when we'd seen the Bavarian Alps in the distance. The navigator came up and pointed out Mont Blanc, away on our port side. He was able to identify it from its shape because he'd actually climbed it, and he was telling us how he was beaten by the weather when he got to within six hundred feet of the summit. Immediately we got to the other side of the Alps, with no snow about, it seemed by comparison, intensely dark for a bit. It was like coming out of a lighted room into the black-out. Soon after that we started to glide down, losing height very gradually and arrived slightly west of Turin. Other planes were already over the target because we could see their flares and there was a barrage of anti-aircraft fire in the sky. Our target was the Fiat works, and the whole time we were looking for them we were still gliding down to our bombing height. Actually we picked the works up in the light of some-body else's flare. They were unmistakable. I've never had such a target before. There seemed to be acres of factory buildings. We almost wept afterwards because we hadn't got any more bombs to give them. Having located our target we flew four or five miles away, turned round and made our run up over it. The wireless operator came along and stood beside me to have a look at the bombing, otherwise he wouldn't have seen anything from his usual position. He's a bit of a wag and when he saw the light flak coming up from the works he said: "Gosh, look at the Roman candles." We made two attacks and as we came round afterwards to have a look, the fires which we'd started were going strong. There was a big orange-coloured fire burning fiercely inside one block of buildings. Having finished the job, we climbed to get enough height to cross the Alps again. Altogether we were over or round about the town for three-quarters of an hour and whilst we were circling to gain height we saw somebody hit the Royal Arsenal good and proper. Going home, the Alps didn't look quite the same. The moon had almost set then and the mountains had lost their vivid whiteness. The last two hours of the journey home were, frankly, plain misery. It started with the aircraft suddenly beginning to get iced up. I tried to climb, but she wouldn't take it. Ice was coming off the airscrews and hitting the fuselage. We came down to about seven thousand to thaw out and then we ran into an electrical storm. All this time we were in cloud. It was frightfully bumpy and the aircraft was bucketing about all over the place. At one point the front gunner called me up and said: "Are you quite sure you're flying the right side up, because I think I can see white horses in the sky." That was when we were over the North Sea. When eventually we left the clouds we had to come through snow and sleet and the final bit of the journey we made in a howling gale which reduced our ground speed a lot. Never had we ever taken so long to get inland to our base from the coast, but we got there safely in the end. A couple of Defiant pics this week - nothing to do with the story.  Defiants of No 264 Squadron at Kirton in Lindsey.  Sqn Ldr Philip Hunter (extreme left) of No 264 Squadron holds a briefing. He and his gunner, Fred King had achieved much success during the Battle of France. Hunter was awarded the DSO and King received the DFM and was commissioned from LAC. They failed to return on August 24th, having been last seen chasing Ju 88s following an attack on Manston.

Last edited by RedToo; 04/30/10 07:32 PM.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3008313 - 05/07/10 09:05 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

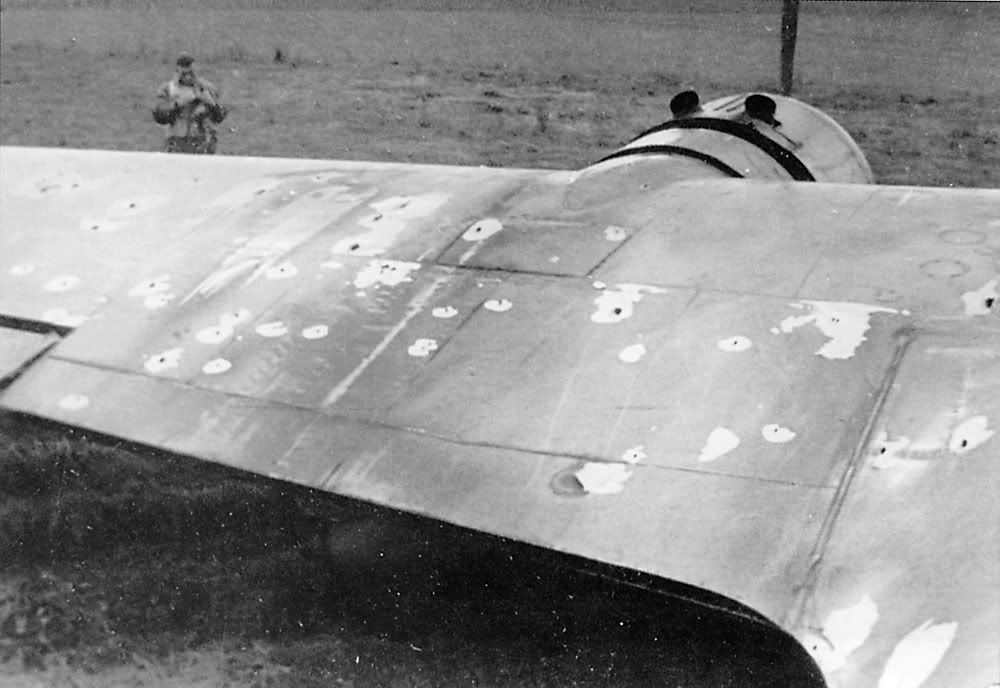

Part 60. December, 1940 TORPEDOING A GERMAN TANKER TOLD BY A WING COMMANDER Aircraft of the Coastal Command of the R.A.F. have had considerable success lately in torpedoing enemy shipping from the air. The commander of a squadron which has been engaged in these attacks, tells you how they are carried out. THE squadron of Coastal Command which I command has lately had the job of doing from the air what the U-boats attempt from under the sea�that is, the job of torpedoing enemy shipping. The U-boats which manage to slip past the Navy can find British shipping all over the oceans�we ourselves often fly over huge British convoys during our patrols. But the German ships can only creep along their own coastline, or that of countries which they have occupied, slipping along close inshore under cover of their land batteries and fighter aerodromes, escorted by "flak-ships". So that's where we have to go to hunt the German ships. If we run across enemy aircraft on the way over, we fight them. We also do reconnaissance, take photographs, and bring back information for the weather people. But our main targets are German supply ships. They are our big game. And when we find them, we attack them with tor�pedoes, which are slung from the aircraft and launched from the air. You can take it from me that the squadron scoreboard isn't too bad so far, and although we've only been operating a short time, many thousand tons of German shipping will never see its own harbour again. The air crews of my squadron, in order to achieve this, fly in all sorts of weather�rain and storm and mist. They cheerfully run the gauntlet of the enemy's coastal defences, flying where the Germans do not always expect to see a British aircraft. So much so, that when the other day one of our aircraft suddenly swooped through the mist on to a German mine-layer, itself heavily armed and surrounded with flak-ships, the captain evidently mistook the aircraft for a German. For he ran up and down his bridge, flashing the signal "U" at our aircraft. "U" is the International Code for "You are running into danger". It might have been more appropriate the other way round. To give you an idea of what this job is like, let me tell you the story of one actual sinking of an enemy ship. It was carried out by a crew of four�the pilot, the navigator, the air gunner and the wireless operator. I would have liked the pilot to give you this talk instead of me. But unhappily that cannot be. The other day, on a similar mission, his aircraft failed to return. He was last seen going into all the shell-fire imaginable to make sure of his aim before releasing his torpedo. So here is the story of the sinking of an oil tanker, which they carried out only the other day. I telephoned Dick, the pilot, that afternoon in his flight office at the aerodrome, to tell him he was off on a roving commission. Then I met the crew of four in the operations room, to tell them what area they were to search, and to give them all the weather information received from other pilots�actually it was wretched weather, with rain, low clouds, and very poor visibility. Dick went off to see the torpedo properly shipped on his Beaufort and within an hour they had taken off. They flew over to the Dutch coast, popped into one or two harbours to see what shipping was about, and then set off along the coast-line, periodically dodging bursts of fire from the German shore batteries and flak ships. They had practically reached the Danish coast, still in this filthy, grey weather, when they suddenly came upon two big German ships escorted by a flak ship. The attack was all over in a minute or so. The pilot headed straight for the larger ship, a 7,600-tonner. He called to his crew that he was about to attack. He and the navigator hastily worked out the ship's course and speed, and the air-gunner was warned to watch out for the run of the torpedo. Flying a few feet above the water, and at very close range, the aircraft released its torpedo. Then the pilot had to turn violently, only just missing the bows of the ship with his wings, and coming close enough for the navigator to read the name painted on her. About five seconds later the gunner shouted: "Whoopee! We've got her." And then: "Gosh, she's up in flames." They circled round, in spite of flak, and saw the ship ablaze�she was an oil tanker. Flames reached eighty feet above her and smoke 400 feet above that. They brought home a photograph of her, which you may have seen printed in the newspapers. And when they got back, they confessed to me that they had turned the return journey into a sing-song inside their aircraft. I never saw four fellows better pleased in my life. Pics of Dornier Do 17s this week.  This Do 17 crash landed in France with more than two hundred hits. That number of hits indicates that at least two British fighters fired most of their ammunition into it from short range. On the original print of the wing more than fifty bullet strikes are visible. Indicating the weakness of the .303-in machine guns fitted to British fighters when used against enemy bombers.  Dornier Do 17s in battle formation. The formation was designed to be easy to fly, while providing crews with the greatest possible concentration of defensive fire-power in the all-important rear sector.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3011954 - 05/14/10 09:24 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

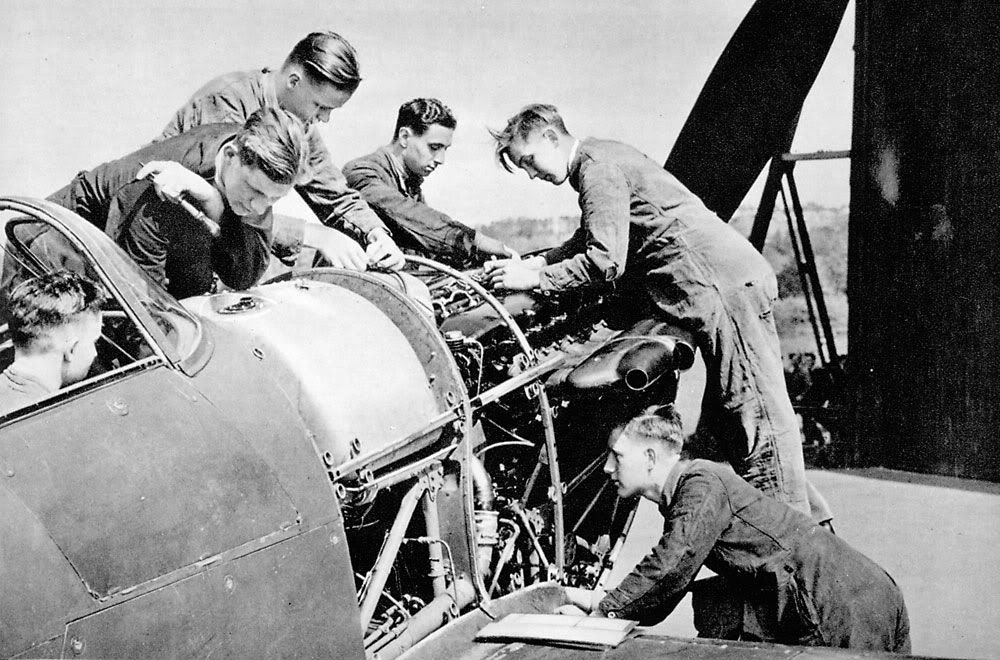

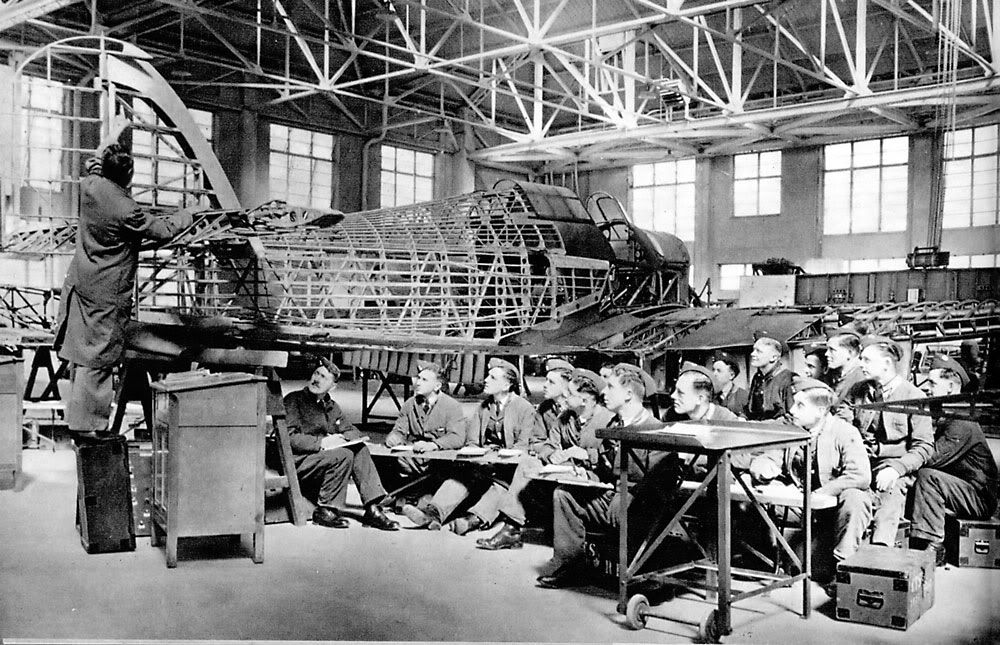

Part 61. December, 1940 WORK OF THE MAINTENANCE CREWS BY A FLIGHT SERGEANT OF FIGHTER COMMAND The British fighter pilot has proved himself supreme in combat. There are several reasons why. Firstly, he is well trained, secondly, he is flying the best fighters in the world and thirdly, his aircraft is always kept in tip-top condition. To see that his Spitfire or Hurricane is fighting-fit every day and often many times a day, is the work of the maintenance staff. The author of the following account is a flight sergeant in charge of the maintenance crews of a Hurricane flight. The squadron has destroyed 100 Nazi raiders. Fighter Command's first V.C., Flight-Lieutenant Nicolson, was serving in this squadron when he won his decoration. You can take it from me that the maintenance crews are "flat out". Each aircraft has its own crew. As a result everybody is very proud of the fighter in his charge. And a healthy rivalry develops, too. They are like the boys in racing stables who groom their own particular horse, call it pet names, slap it affectionately and kiss it when it wins a race. When they hand it over to the jockey on the big day they believe that their horse is the best that money and care can produce. The maintenance crews on our Hurricanes are like that. I've seen them in the morning, taking the covers off the aircraft, slap it under the belly and say some�thing like: "Come on, you beauty, plenty of Huns to-day, please!" Once a pilot came back from a battle after shooting down a Junkers 88 and two Messerschmitts. The crew that serviced that Hurricane did a war dance and went about swanking to the other crews. They regarded the three at one crack as THEIR, work. Then I've heard them comparing notes like: "How many bullet-holes did yours get back with to-day?" And the reply: "Only one." And then the first crew say triumphantly: "One bullet? That's nothing! We had seven in ours, and they were all repaired in no time!" But that is where the rivalry ends�with good-natured high spirits. It begins with real, hard work, but competitive work, mind you. There is keen competition when the aircraft come back to re-arm and re-fuel. One day, when the squadron landed almost at the same time�I mean in quick succession�it took the maintenance crews only eight and a half minutes to re-arm and refuel the lot. Eight and a half minutes from the moment the first machine landed to the time the last machine was ready for the air again, each aircraft having been filled up with petrol and ammunition for another battle. We work long hours, but we don't mind. Our day starts at dawn. The first task is to take the sleeves off the main planes and the canvas covers off the cockpit hoods. Then the pickets which have tied the aircraft down all night are taken up. The fitter gets into the cockpit and the rigger stands by the starting-motor. The engine is started up and run until warm. Then, should there be an alarm, there will be no trouble about starting the aircraft or getting it off the ground quickly. Suppose there is an alarm. The message comes through by telephone and immediately I dash out and shout the signal for every crew to go to their own particular aircraft and start up. At the same time the pilots come from their crew-room and scramble into their aircraft. Sometimes the pilot arrives at the same time as the crew, but as often as not the engine is started when he races up. If it takes more than two and a half minutes from the warning to the time all the aircraft are in the air�well, there is usually an inquest at which I am the coroner. If there has been any delay I want to know why, because every second is precious and might mean the difference between ten Huns or no Huns at all. Well, eventually, the fighters come back. Perhaps they have been in action. As soon as the first one lands it taxis towards the waiting ground crew. A tanker goes alongside to fill up the petrol tanks. At the same time the armourers re-arm the eight Browning guns. The rigger changes the oxygen bottles and fits the starting-motor to the aircraft so that it is ready for the next take-off. Then the rigger takes some strips of fabric which he has brought with him from the crew-room and places them over the gun holes. It helps to keep the guns clean and also helps to keep the aircraft 100 per cent efficient in the air until the guns are fired. Meanwhile, another member of the crew searches the aircraft for bullet holes and the electrician goes over the wiring and the wireless mechanic tests the radio set. Every little part of the air�craft is O.K. before the machine is pronounced serviceable again. All this process should take no more than five minutes, but we allow seven minutes for the whole job. As I said a moment ago, we once serviced a squadron which came back more or less together in eight and a half minutes. If a Hurricane comes down with a few bullet holes, it is my job to see if the injuries are superficial or not. If there are holes through the fabric, we quickly patch them up. If there is a bullet through the main spar, then it is a case of a new wing. Should a machine be found by me to be unserviceable, a spare aircraft is brought for the use of the pilot until his own machine is ready. So the day goes on, this routine happening perhaps two, three, or four times a day. Finally, at nightfall, we make the daily inspection. The armourers clean the guns, the fitter checks the engine over, the rigger checks round the fuselage and cleans it, and the wireless man checks the radio set. The instruments man checks the instruments. When everything is O.K. and the neces�sary papers signed, the machine can be put to bed. The sleeves are put on the wings, the cover is put over the cockpit, the pickets are pegged into the ground and the machine left, heading into the wind, until dawn. It sometimes happens that an aircraft needs, perhaps a new undercarriage. That means working far into the night until the aircraft is ready to fly again. I remember working with other members of the crew fitting a new undercarriage to a Hurricane which had been damaged on landing. We started at four o'clock in the afternoon and we didn't finish until four o'clock the next morning. But when that aircraft came back the next day with a few Huns to its bag it made all our labour well worth while. Like the pilots, we eat our food when we can. If the squadron is sent off at, say eleven o'clock in the morning, and we know that they probably won't be back for at least an hour, we go for lunch. But we always leave a spare crew on duty to deal with any aircraft�maybe from another squadron�which might land. The crews take great pride in the aircraft in their charge. They call their Hurricanes by pet names, always starting with the machine's appropriate letter. Thus you get a machine with the letter "F" called Freddie, "Q" Queenie, and so on. They paint mascots on the aircraft, too. "Freddie," for instance, bears a picture of Ferdinand the Bull. Another aircraft has a witch on a broomstick, another has George and the Dragon, and they usually paint a tiny swastika along one panel for every Hun the pilot has got. They keep the aircraft spotlessly clean, too. After each trip it is wiped clean of oil and every other day the Hurricane is washed and scrubbed with soap and water. And they wash behind the ears, too, as though they were washing a small schoolboy! As you may guess, there is not much time for fun and games. Most of the recreation�darts, shove-halfpenny and such like, are played in the camp, but now and then the airmen get a day off to enable them to find relaxation outside. But generally, they are quite happy staying in camp. During the summer-time our hours are from about three-thirty a.m. until ten-thirty p.m., but in winter the hours of daylight are short, giving us a chance to rest. May I say a word about the fighter pilots? I think they are a fine lot�as good as R.A.F. pilots ever were. I've been in the Service since I was a boy in 1923�I'm only thirty-three now. But I've worked for some grand people. Once I was with some members of the Schneider Trophy teams�when they were instructors at a Central Flying School teaching younger men� now fighter pilots, I suppose�to fly. I am Cornish, though my wife now lives with our three children in the village of Ryther near Selby, Yorkshire. My family are boatbuilders in Falmouth and a great-great-grandfather or something like that, of mine, was a Petty-Officer in Nelson's Victory. He helped to conquer one dictator. I hope to do my bit in conquering this dictator.  Recruits in training, at work on a fighter engine.  The King and Queen watch a rigger under training.  Rigging instructions on a Hurricane.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3016117 - 05/21/10 08:29 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 61. December, 1940 R.A.F. TRAINING BY AN ACTING PILOT OFFICER UNDER INSTRUCTION IT'S several months now since a very Junior Acting Pilot Officer first put on, perhaps a bit self-consciously, a very new R.A.F. uniform, and admired himself in a mirror. I remember how naked he thought the uniform looked without the pilot's wings over the left top pocket, and how he wore his greatcoat on every possible occasion, to cover up that enormous gap of blue cloth where, one day, he hoped wings would grow. Well, to-day, that uniform isn't quite so new, and its wearer perhaps not quite so self-conscious; but he still puts on the great�coat, even on a sunny day, because those wings aren't there yet. In a few weeks maybe�but, at the moment they're�well, shall we call it�semi-sprouting. It's about this half-Hedged state of mine, and how I've got to it, that I'm going to talk now. When I first joined the Service I was plunged into something which I didn't think I was going to like very much. It was called a disciplinary course, and, being a very undisciplined sort of person, I approached it in a "nasty medicine" sort of way�with a "I know this is going to do me good but all the same I don't want to take it" sort of attitude. But I must say�I rather enjoyed it. I was taught how to march instead of slouch; how to be drilled, and to drill, and, very important, how, when, where and whom to salute. After the first few hours of this I realized that there was a higher art on the barrack square. This surprised me, rather like finding out at the age of twelve that rice pudding is really quite palatable. But it was so�as anyone who has ever seen the shambles resulting from giving, say the command "Halt", on the left, instead of on the right foot, will appreciate. By the time I could get a squad on the move, and halt it again without having everyone falling over everyone else's feet, I was posted to an E.F.T.S. I became, in fact, a pupil pilot�or, in other words�a "Nit"�the derivation of this term is obvious� and, in most cases, I fear�justified. It certainly was in mine. An E.F.T.S. is an Elementary Flying Training School, and there I joined in with a lot of other "Ni��"�er�pupil pilots�who had just come from an Initial Training Wing. There they'd already had instruction in several useful things like Morse, and navigation and armament�which put them a bit up on me � because I didn't know a "da" from a "dit" at Morse, or a Browning breech block from a sewing-machine shuttle. The main job of the E.F.T.S. was to teach us to fly. But, in the case of people like me, who thought they could fly a bit already, the instructor had a double job to do�first showing us that we couldn't fly and then teaching us the right, proper official and R.A.F. way. My instructor (and I hope he isn't listening) was a very tough and exceedingly competent Flight-Lieutenant, with that odd mixture of patience and explosiveness which forced his pupils to keep on their best performance all the time they were flying with him. I shan't forget his remark to me on my first bit of dual. He told me to do some turns. I pushed the aeroplane round to the right in my most polished manner. Silence from the front cockpit. So I pushed her round to the left. Still silence. I sat and waited. There came, in my earphones, a long over-patient sigh � and then a gentle voice: "You may call those turns, laddie, but, as far as I'm concerned, they're just changes of direction." The machines we flew at E.F.T.S. were Tiger Moths, open cockpit biplanes of great stability and little speed. We grew to love them�they were such very forgiving aeroplanes. The one I flew mostly�old 84�was very much so�she forgave me many things�crooked loops, bad sideslips, flat turns, bump landings �so much, in fact, that when my flying got a bit better, and 84 had less to put up with, I felt like giving her a lump of sugar, or an extra ration of oil, or something, in return for past favours. Most of my fellow "Nits" went solo after about seven or eight hours dual. The ordinary flying syllabus included slow rolls; stalled turns; rolls off the top of a loop; spinning at least once every two hours, and other gentle means of disturbing one's half-digested lunch�and also we had to do forced landing practices�cross-country flights, and one or two other indispensable exercises. In our course only three pupils failed to make the grade, and this I might say, involved no shame on the people concerned at all. The R.A.F. is purely voluntary, and if pupils decide they don't like flying�or that they aren't good enough�then they're at full liberty to say so, and to turn to something else. One of our instructors put it rather well when talking to a pupil who'd just been suspended. This instructor�incidentally in civil life he was a well-known private owner and an M.P.�said: "There's nothing wrong in not being able to fly. What would seem wrong would be if everyone could." Our ground work was, at least for me, pretty hard, especially the Morse. I managed to learn the code and get up to about six or seven words a minute, sending and receiving, on the buzzer. But, receiving signals on the Aldis lamp, foxed me completely, and, in the examination, I'm sorry to say, I failed on the lamp �the only one on the course to do so. I'm only just managing to cope with it now after another spell of work at my present place, but I fear I shall never grow to love it. We had quite a stiff examination on our ground subjects, including navigation, airmanship, rigging, engines and armament. I got through all right, I think, but I'm still waiting for a note from the examiners to tell me that the proper answer to "What would you do if your aircraft caught fire in the air?" is not "Dial 'o'." And a last word about the instructors themselves. Someone recently published a bit of verse which summed up their lives. He wrote: "What did you do in the war, daddy? How did you help us to win? Circuits and bumps and turns, laddie, And how to get out of a spin." And very true it is. These men�experienced pilots all of them�are doing one of the R.A.F.'s greatest and most unpublicised jobs. Hours of circuits and bumps, correcting the same old faults, getting "Nits" off solo�and then seeing them go away�having their places taken by another bunch, who're going to do the same silly things in the same silly way all over again. Yet, on the whole, most of them say it isn't too bad, and that they become first-rate psychologists, which probably they do. But the real joy of an instructor's life is his collection of stories of the things "Nits" have done. There is the instructor who, to give a titled and illustrious but rather nervous pupil some more confidence in landings, held his hands above his head as the plane was coming in, so that the pupil could see that he alone was doing the landing. The plane came down, bounced, came down, bounced again, and finally jolted to rest. The instructor looked angrily round, and there sat the pupil, hands held firmly above his head. "Well," he said, "you told me last time round to watch how you did things and then to do them your way, so I did." I had collected a nice lot of stories which I wanted to put in this broadcast, but there's no time, so I'll end the E.F.T.S. chapter of my R.A.F. experience with another quotation from my instructor, which sums up life, from his point of view, for those first flying-training weeks of ours. "Up round�down�bump. I've got her�you've got her� I've got her�(sigh)�I've got her." It's been a week or so now since I left E.F.T.S. for a more advanced Flying Training School�where I'm now busy flying twin-engined machines, and preparing for another and stiffer examination. I'll try to let you know how I make out�and I hope it'll be all right�because it's the "wings" exam., and well, I am getting rather tired of wearing my greatcoat.  De Havilland Tiger Moth, a valuable training aircraft.  Miles Master, a miniature fighter with a 530 h.p. Rolls-Royce engine capable of 264 m.p.h., used for training fighter pilots.  The Harvard, an American aircraft used extensively for the advanced training of pilots.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3020715 - 05/28/10 07:58 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

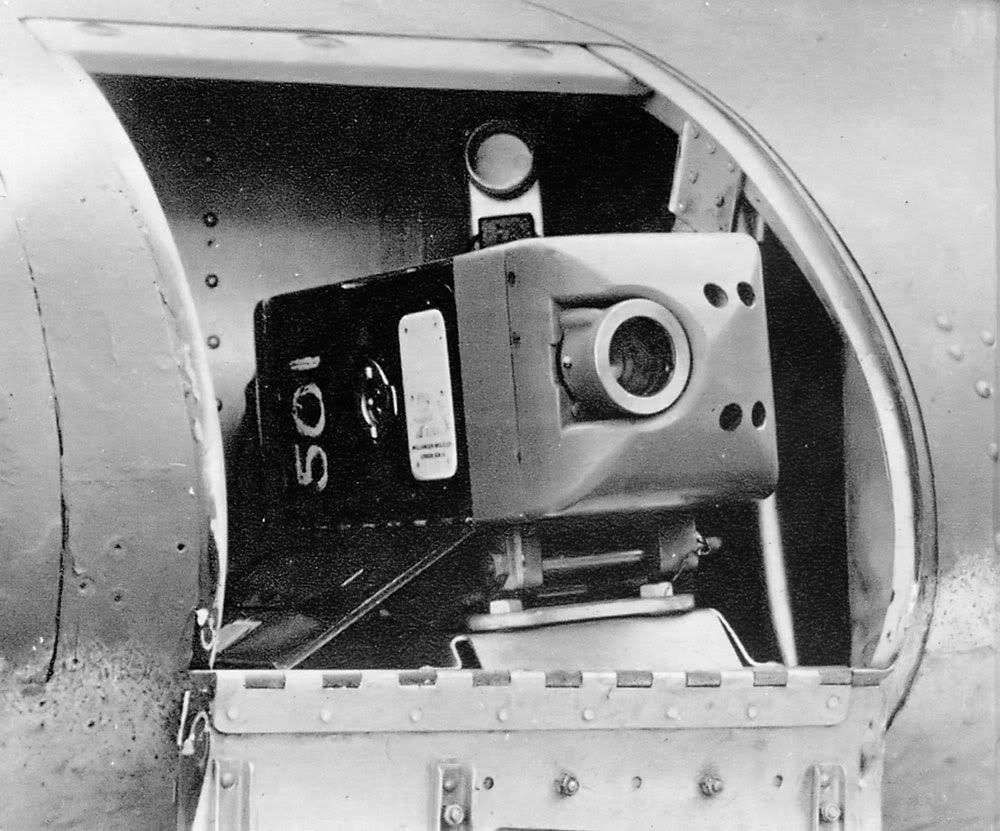

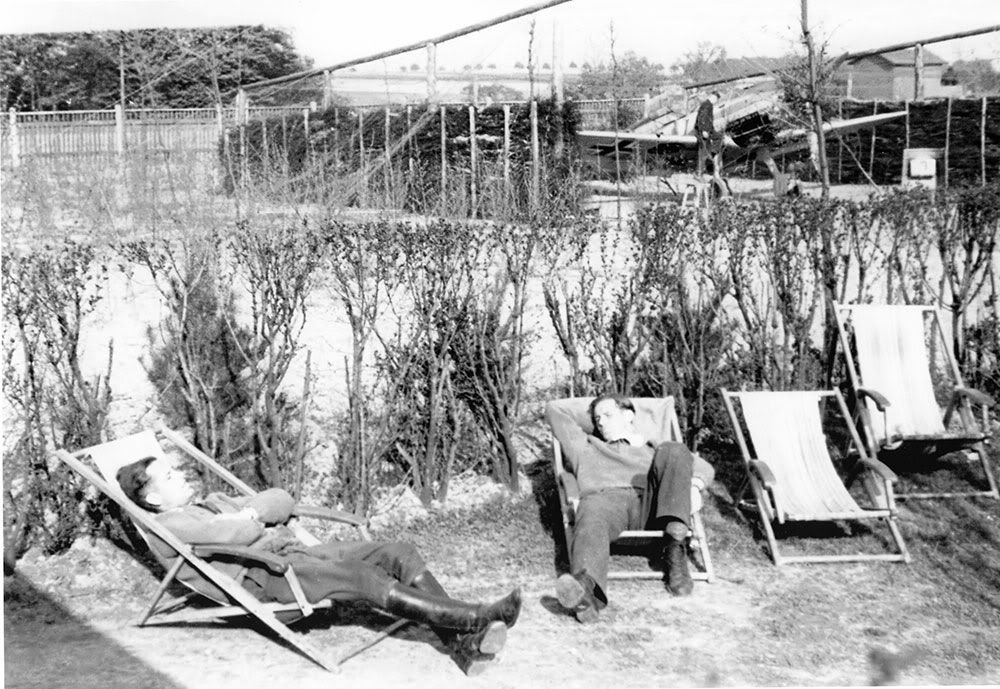

Part 63. December, 1940 ATTACK ON MANNHEIM BY A SQUADRON LEADER The speaker, a Squadron Leader in one of our heavy Bomber squadrons, describes a recent raid on Mannheim which has lately received a great deal of attention from the R.A.F. He holds the D.F.C., awarded for his work on the night of the attack on Munich. THE operation the other night against Mannheim was on a pretty big scale; aircraft from a number of squadrons were operating. The general idea was to send in the early ones with incendiaries so as to light up the target, then for the main force to come along with heavy stuff. The operations of the main force incidentally were spread over a period of six or seven hours. The station commander had a word with the captains and crews before we left. He said he was expecting some very good results. He also mentioned that, as there would be a lot of aircraft con�centrating on Mannheim, he wanted us to go in, bomb and come out again as quickly as possible. We left at regular intervals. It was important to keep strictly to the scheduled take-off times because of working in with the other stations, so as to make the bombing a more or less non-stop affair once it started. Just when we were due to get away it started raining cats and dogs. One could just see a few blurs of light indicating the flare-path and that was all�rather like driving a car in heavy rain without a windscreen wiper, only more so, if I may put it that way. However, we all got off all right. The cloud base was at a thousand feet, and we had to climb up to get through it. We were climbing rather slowly, too, because we were carrying a heavy load. Once we got above the clouds, we were in bright moonlight and the navigator got his sextant out and started taking Astro sights to check up on our position. Normally, when you cross the Dutch coast you reckon to get a bit of flak thrown up at you but this time, being still above cloud, we got nothing at all. We flew on, keeping straight and level. Then, fifty miles inside the Dutch coast, the cloud cleared and we saw the ground for the first time since we'd taken off. Altogether, it was a very uneventful trip out. In Germany they'd had a fall of snow which was quite a help to navigation. When you have a light fall, as this was, the important things� woods and rivers, lakes and towns and villages�all stand out much clearer, and so, with the moon very bright, we pin-pointed ourselves quite easily as we went along. We were some distance from Mannheim when the front-gunner reported heavy flak ahead. We were then about ten minutes away heading straight for it and we knew it must be Mannheim. The stuff was coming up in bursts and then dying away, then breaking up again, spasmodically. I told the navigator to prepare for bombing and he came up into the bomb aimer's position in the nose of the aircraft with his map. Having done that, he had to check up on the bomb switches, select his bombs, and we determined the length of the stick. One can drop a widely spaced stick or a close one. This time I had decided on a very close one. As we approached, I could see fires already well under way, and it was obvious that the blitz was in full swing. We picked up the Rhine, followed the river up and then started to take avoiding action because there was quite a lot of flak, mostly light stuff, coming up. It's all tracer, this light stuff and you can see strings of it coming up. The flak seemed to be pretty continuous by now. When it gets like that, one just goes through it, doing evasive stuff. I don't think flak deters any of the fellows from carrying out the job. One sometimes sees German reports of the barrage turning our aircraft back. In my opinion, that's just nonsense. As we got a bit closer, the navigator called out "Ready", and I levelled out and opened the bomb doors. You only do that at the last minute because when they are open it makes the aircraft drag a bit, so you open the throttles a little to compensate the slight loss of speed. You tell the navigator "Bomb doors open, master-switch on," and he repeats that back to you. He will probably make a few corrections to course�"left, left, right, right, steady," and so on�and when he's bombed he calls out "Bombs off". As a matter of fact you can feel the bombs go. You get a slight lift in the aircraft and it immediately becomes much more lively. I must say, I always find it a bit of a relief directly they've gone and one knows that one's done the job one was sent out to do. Well, on this occasion everything went normally and as soon as the bomb aimer said "O.K., sir, bombs burst," I put the aircraft into a steep turn to let the crew have a look. There were three groups of huge red fires burning down below and spirals of heavy black smoke rising above the town. The fires were increasing in intensity all the time. Then, we set course for home, we could see other people bombing as we came away. I told my rear gunner, as I always do, to note the time when he could no longer see the fires, and we were about sixty miles away when he called out and said he'd lost them. Nothing very much happened on the way back. Coming down through the clouds over the North Sea we started to get iced up a bit. Pieces of ice were threshing off the air-screw and coming through the fabric of the fuselage, but we got back without any real trouble. Everybody had seen much the same sort of thing as we had�fires and still more fires �and the general feeling in the squadron was that the show had been a great success. A couple of Spitfire pics I�ve just stumbled across:  Re-arming.  Re-fuelling.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3025057 - 06/04/10 07:11 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 64. December, 1940 RAID ON TARGET NEAR VENICE BY A FLIGHT LIEUTENANT The speaker is a twenty-three-year-old Flight Lieutenant in a heavy bomber squadron. He describes a recent flight from England to Italy to bomb a military target at Porto Marghera on the Italian mainland near Venice. THAT was the longest trip I had ever done. One knew it was going to be a pretty tiring business�ten hours or so there and back�on the other hand one was very pleased to be given the opportunity of doing something that was really new. Once before the squadron had been briefed for Italy and we'd been disappointed by having the operation cancelled because of bad weather. This time everything looked absolutely perfect from the word 'go'. It was just after six o'clock in the evening when we got off. The navigator pin-pointed himself on the coast, then we made a slight alteration of course and got our next pin-point on the other side, crossing the North Sea in comparative darkness because the moon hadn't risen yet. I decided we were a little too low to cross the coast safely in case we hit a heavily-defended area, so we turned left along it to gain an extra fifteen hundred feet. While we were gaining height in that way a fighter passed very close to our tail, but he evidently didn't see us. At any rate, he didn't attack. The rear-gunner, of course, wanted to have a crack at him�all air gunners always do�but it had come and gone too quickly for him to get his sights on it. We were taking as direct a route as possible to avoid passing over neutral territory. Seventy miles inland and ground became snow-covered. It was a fairly cold night�minus twenty degrees at twelve thousand and, later, at fifteen thousand, minus twenty-five. We were climbing gradually all the time, until we'd reached a good height for crossing enemy territory. And we continued at that height. It was then just after nine o'clock. Half an hour before reaching the Alps we started to climb again and went up to fifteen thousand. If it hadn't been such a good night from a weather point of view I should certainly have gone higher than that to get across. As it was, the winds were slight and there was no cloud, so there was no danger either of unpleasant bumps or icing conditions. We came to the foothills of the Alps after about three and three-quarter hours' flying. It was a nice clear night with every�thing in our favour. A lot of people burble about the beauties of the scene. Well, personally I must say, I was rather more impressed by the fact that if anything went wrong there was little chance of coming down safely, except perhaps by parachute. It was difficult to tell one peak from another. We were up at twelve or thirteen thousand feet. I suppose it must have taken about an hour from the com�mencement of the foothills on one side until we were clear of the foothills on the other side. The moon was still not up and, having crossed the Alps, it wasn't at all easy to see any detail on the ground now that there was no snow to help us. In fact, it was so dark that we turned along the river, thinking for a moment that it was the coast. Eventually we came out some miles from Venice. The navigator recognized Venice from the form of its waterways and then we turned along the coast. Mean-while the bomb-aimer was adjusting the various settings on the bomb-sight, such as, height, wind and air speed, and trail angle. There was still no moon but a coast is always easy enough to follow on a clear night, however dark it is. We could see the outline of Venice very clearly defined as well as the famous lido and the bridge connecting Venice with the mainland. The target was a petroleum works which lay on the mainland just west of the end of a bridge, near the docks. Its position was quite obvious as we knew exactly where it was and we could have bombed it without a flare, but I decided it was quite worthwhile dropping a flare and having a look at the place before we attacked it. We ran up along the bridge, dropped the flare, did one circuit round it and then went out again and came in to make the bomb�ing run from the same direction. The navigator watched the bomb burst on the target area and we did another circuit and saw parts of the plant going up in flames as the incendiaries dropped. There was a train crossing the bridge at the time and the explosion must have been a bit of a shock to the unsuspecting Italian passengers. Altogether, we were about twenty minutes over the target area. Then we turned for home, and as we approached the foothills of the Alps on the way back, the navigator who was in the astro hatch, said it looked as if the moon was sitting on top of a peak. We climbed to fifteen thousand again to get over the high part. The Alps looked a little more friendly now. That may have been due to the moon, but probably the fact that we were on the homeward journey had something to do with it too. Frankly, we were none of us sorry to see the last of the mountains. Just this side of the Alps we ran over cloud which blanketed out the ground. Then, having got clear of that, there was a lot of ground haze which made visibility very poor and again we were flying on dead reckoning navigation. On the English side of the Channel there were ten-tenths cloud at four thousand feet and we were flying above it, in fact, we were not able to see the ground at all. I was pleasantly surprised when we got the "Over" signal�that's to say a signal from the ground, "You are over the aerodrome." However, my aircraft had behaved magnificently over the whole journey, and had taken us there and back in the very good time of nine and a half hours.  Junkers Ju 86P high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft. This advanced aircraft featured a pressurised cabin and was powered by two highly supercharged diesel engines, enabling it to operate at altitudes above 37,000 feet, where it was immune from fighter interception during the early war years.  Spoils of war. Royal Air Force personnel pumping petrol from a Ju 88 of KG 54 that crash-landed near Tangmere into a private car belonging to one of them. Such misuse of captured enemy material was illegal, but those in authority turned a blind eye to it.

Last edited by RedToo; 06/04/10 07:12 PM.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3029520 - 06/11/10 09:54 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

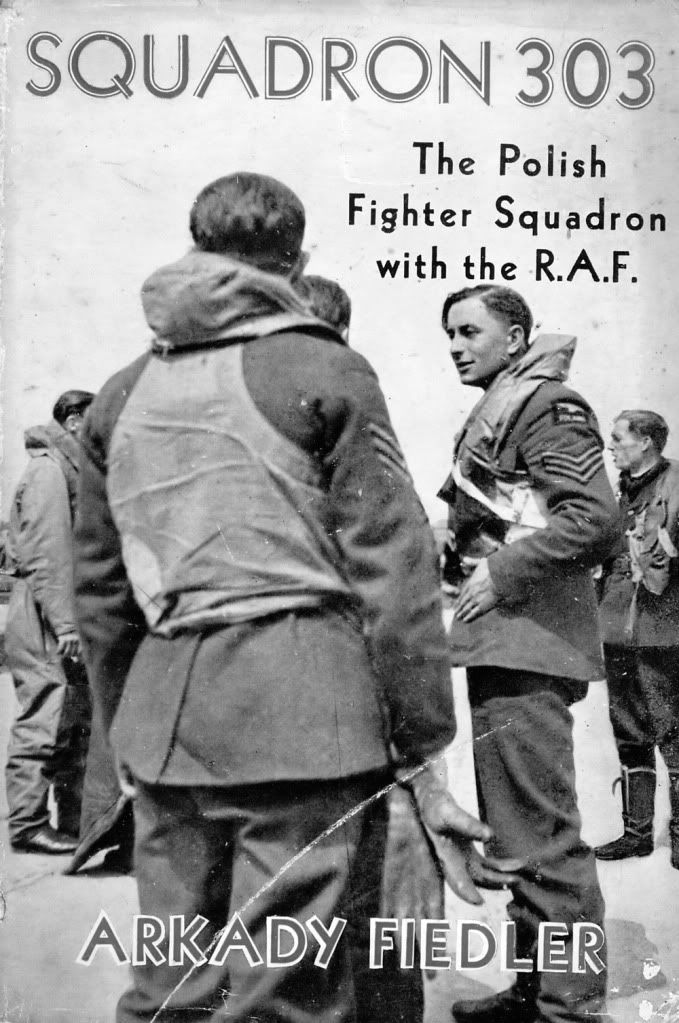

Part 65. STORY BY A CANADIAN SPITFIRE SQUADRON LEADER The author of the following account is a young fighter pilot of whom Canada may well be proud. To-day the leader of an R.A.F. Spitfire squadron, he had flying in his blood ever since he went to school in Winni�peg, Manitoba. He made his first flight when he was fourteen, and he learned to fly an aeroplane two years later. At seventeen, he was the youngest licensed flyer in the Dominion and when he got his commercial licence, two years later, he was the youngest commercial pilot. So he sailed for England in 1935 to join the R.A.F., and within a fortnight of his landing in Liverpool he was in the Royal Air Force. Before the war started he had been awarded the Air Force Cross for a particularly dangerous job of flying. Just recently he won the Distinguished Flying Cross, for gallantry in action as the leader of a Spitfire fighter squadron. WELL, I've been lucky enough to see quite a lot of this war so far, and believe me, I hope I'm going to see a lot more of it before it's through. I want to see, for instance, another afternoon like that of September 27th, when the R.A.F. slapped down more than one hundred of Goering's Luftwaffe. At the time I was a flight commander in the now famous Polish squadron, flying Hurricanes, and with several other squadrons we went up to meet the Germans. A terrific anti-aircraft barrage was being put up round London, and from where we were we could see the capital gradually become encircled by a ring of smoke puffs from the bursting shells. Then we saw the hordes of German bombers and escorting fighters coming in over Kent. As R.A.F. fighters got stuck into them, you could see them falling away, plunging down with smoke pouring from them. It almost seemed that there was an invisible barrier over a certain part of Kent and that as soon as the bombers reached it large numbers of them suddenly began pouring out smoke and going down. It was an amazing sight and if I hadn't seen it all happen, I would never have believed it. All this was happening in the few minutes before we arrived. Our squadron, by the way, was accompanied at the time by a Canadian Fighter Squadron, so I felt quite at home as we went into battle. I got behind one bomber and went straight in at him. When I was about seventy-five yards from his tail, his rear gunner suddenly realized that I was there and opened fire. I fixed him with my first burst. Then I pressed the gun button again and kept my thumb on it for several seconds, and shortly afterwards he began to go down in flames. I watched him and saw him go into the sea with an almighty splash. Another German bomber which crossed my sights got a quick burst from another pilot and as he went gliding down I saw a red glow appear under his belly, and as the glow got bigger, so his dive got steeper. He exploded before he hit the water, and it began raining little pieces of aeroplane from the spot where he had blown up. There was a lot of milling around in the sky that afternoon, and when the Canadian squadron and ourselves got back we found that we had collected more than a dozen Huns between us. The day's score, as I said, was over the hundred mark. I got two bullets in my Hurricane that day, and they are the first bullet holes I have had in my aeroplane since the war started and I hope the last. I want to tell you right now that it was a grand experience fighting with the Poles. When the squadron was first formed at the end of July the nucleus consisted of an English Squadron Leader and two flight commanders, of whom I was one. The Poles who came along had plenty of fighting experience. They had fought in Poland, and later in France, and when we got together in the early days of August we were all flat out to have a crack at the Huns. By the end of the month we had taken our place in the front line. The first morning in the front line we were sent to escort a formation of our bombers; we ran into a raid and we got a Dornier 17 first crack. The next day we got six Messerschmitt 109 fighters, and from then on we slapped 'em down as they'd never been slapped before. In their first four weeks that Polish squadron shot down more than one hundred enemy aircraft, and in five weeks we had shot down more than one hundred and twenty. You can take it from me that those Poles were magnificent fighters�and they still are. They introduced their own technique into air fighting. They sailed right into the enemy, holding their fire until the very last moment. That was how they saved ammu�nition and how they got so many enemies down on each sortie. When I started talking, all sorts of incidents come crowding into my mind about this war. I was in France doing a special job in a Spitfire from May until June 16th. Just before the French collapse I remember flying over one part of the country in which there was not a single living thing. Not a head of cattle, not a dog, and certainly not a human being. And then I came upon the refugees and saw, for mile after mile, roads packed tight with people, fleeing before the Germans. At one stretch I should say there were forty miles of road packed solid with refugees. There were tragic sights to be seen on the ground, too. In every hotel the people were lying about all over the place, just snatching a little sleep before moving on. I remember, particu�larly one old woman, with all her worldly belongings in an ancient perambulator. Yet she had a cage hanging by the side of the pram, and in the cage was her cat. They were pitiful sights, but the French were very brave. I got on very well with them, largely, I think, because I am a Canadian. Before, and even after the collapse, you only had to say you were a Canadian and there was nothing that the French would not do to help you. Since I've been back in England I've had my share of excite�ment�and when it's been in the air it's always been most enjoy�able. Some days ago, for example, we saw between sixty and eighty Me. 109s, and though there were only five of us Spitfires at the time, we had a height advantage of some 6,000 feet. We just nipped down on them. The one I got first began to belch black smoke and went streaking down, leaving a tremendous trail of smoke that stayed in the sky for at least ten minutes. Then I had a terrific dog-fight with another Messerschmitt which attacked me immediately afterwards. He could fly, too, could that Hun. He kept swinging up and round into the sun and several times I had to guess where he was as he disappeared with the sun right behind him. I squirted at him several times like that and finally saw him come out of his protecting sunshine with his tail nearly off. The fin and rudder were in tatters. As we rushed towards one another I could plainly see the pilot looking straight at me. We missed each other by feet. As he turned to the left he made a target of himself, so I squirted him for a second. He flicked over on his back and with grey smoke simply pouring out, went straight down towards the Kentish soil. He went into the ground with an awful smack. There was a flash of flame, a cloud of smoke, and when I looked again there was nothing but a gaping hole with a few tiny pieces of scattered wreckage round the edges. I saw some British Tommies run across to the crater he had made and look down. Then they waved up at me and gave me the thumbs up sign. Well, that's the kind of job we're doing and we get quite a kick out of it. Of course, you don't run into Huns every day of the week, but when you do go up to meet him you feel so good that you think you could take on the entire German Air Force single-handed. These Spitfires we're flying may account for some of that feeling�they're certainly good. Altogether now I've done about one hundred and fifty hours' operational flying in this war and I only hope there's going to be a lot more to come.  Pilots of 303 Squadron �The Polish Squadron� on the cover of the book about 303 Squadron published in August 1942. The text of the book can be read here: http://www.archive.org/details/squadron303006829mbpThe language in the translation is even more "flowery" than in the original, but the stories and stats are very interesting, especially seeing how this was the highest scoring squadron with the highest scoring aces of the battle on the British side. Thanks to Woke_Up_Dead for the link.  WAAF mechanics helping the pilot strap into a Spitfire Mk II of 411 (Canadian) Squadron, at Digby in Lincolnshire in 1941.

Last edited by RedToo; 07/04/10 10:59 AM.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3034683 - 06/18/10 08:37 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 66. December, 1940 RAID ON LORIENT BY A CZECH PILOT IT IS just a few nights ago that I am making my first mission with the Royal Air Force against the enemy. I was for four years observer in the Czechoslovakian Air Force. I go to France and I am nine months in France in the French war. Then I come to England with a little ship from Bordeaux. It is a little merchant ship. Eight hundred tons. A little Dutch ship. I am in some camps here and then I go to a Czech depot. I do not speak any English when I arrive. I buy an English dictionary and when I have free time, I learn to speak it: but it is not so quickly. Then, since September, I am in the Czech bomber squadron with the R.A.F. I have a course of navigation which is most painstaking and in October I am ready, but I must wait for my pilot. He is not so ready. We are to fly Wellington bombers. It is very good, the Wellington. So, I am waiting to go for some weeks, but my captain is not yet fully instructed. Then, when he is ready and we are to go, he becomes ill. He has influenza and after more waiting I go on this, my first mission, with another crew. Before this happens I have asked already to go with another crew until my pilot is finally prepared, but this is not possible, for all the other crews are complete and it is not good to chop and change crews. But now I can go. We are on this occasion to bomb the submarine base at Lorient. Our pilot is a sergeant and we have altogether three other sergeants and two officers. Before we go we are briefed most exactly by our own Czech wing commander. The wing-commander tells me that I must find exactly this target to bomb. He gives me the position of anti-aircraft guns and the position of submarines in these docks at Lorient. When we are going out the weather is good. It changes very quickly, the English weather: now good and then after two or three hours it is, perhaps, bad. This was good all the time except that when we come back we have some clouds�but that is not yet. When I come to the French coast I am finding myself a little off my course. You see, I am to be here at a certain point, and I am four miles from this but I fix me by the coast and we go on. The aircraft goes very well indeed. Before we have come to Lorient we have seen a big fire: I think about twenty-five miles away. Also big anti-aircraft fire and searchlights�many of searchlights�and much of anti-aircraft fire. When I see all this I say, "That is Lorient where we are to go", but we are already going in this direction so it is not necessary to make an alteration. We go into the anti-aircraft fire and into the searchlights. They fire at us but the explosions are not of our height. The others with me have already made eight or nine missions with our squadron and have been under fire very often, but for me it is the first time. It looks very nice, I think, and illuminates the night very nicely. We are flying into our target from the north. I go a little to east and turn also back to south. Before this, I have prepared my bomb-sight. Then I am looking and giving the directions for my pilot. I have seen the river and on the right side of the river I have seen here a big building which must be the smithery which is shown for me on my map. I have seen the river very good. It looks a little lighter than the ground and it is quite simple to see. Also I can see the docks. There is no cloud at Lorient: only little patches of mist, but we can see through them quite simply. When we get near we see again the fire that we have seen before, but now he was not so great: he is dying. Since I am to make the bomb-aiming I am lying on my stomach in the nose of the aircraft looking down on all this. I have, besides heavy bombs, many incendiaries. When I have the target in my bomb-sight I tell to the pilot "Straight on". He goes straight on and when I have got this target as I want it I press the switch. I can see the bombs go from the aircraft. Just for one moment. No more. The rear gunner says he has seen the explosions from the bombs. Then it is most remarkable what happens. There are between twenty and thirty big explosions and soon they are making altogether one big fire. There is much talking in the aircraft at all this and everybody asks the others to look at what is happen�ing. The front gunner is pleased and cries away that it is the biggest fire he has seen in all the nine missions he has made. All this time, they are firing at us also heavily, but again it is a little down and not of our height and we are not hit. It is very good because this fire had held on so well that when we go back from the target twenty minutes the rear gunner is finding it still possible to see the fire. When we are going back, there is more fire at us for one or two minutes, but still we are not hit and we come home without difficulty. When we are home once again the wing commander is very pleased with what we have done and tells us that this was a very good show.  Vickers Wellington Bombers. Two Bristol Pegasus engines developing 2,000 h.p.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3039731 - 06/25/10 09:13 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

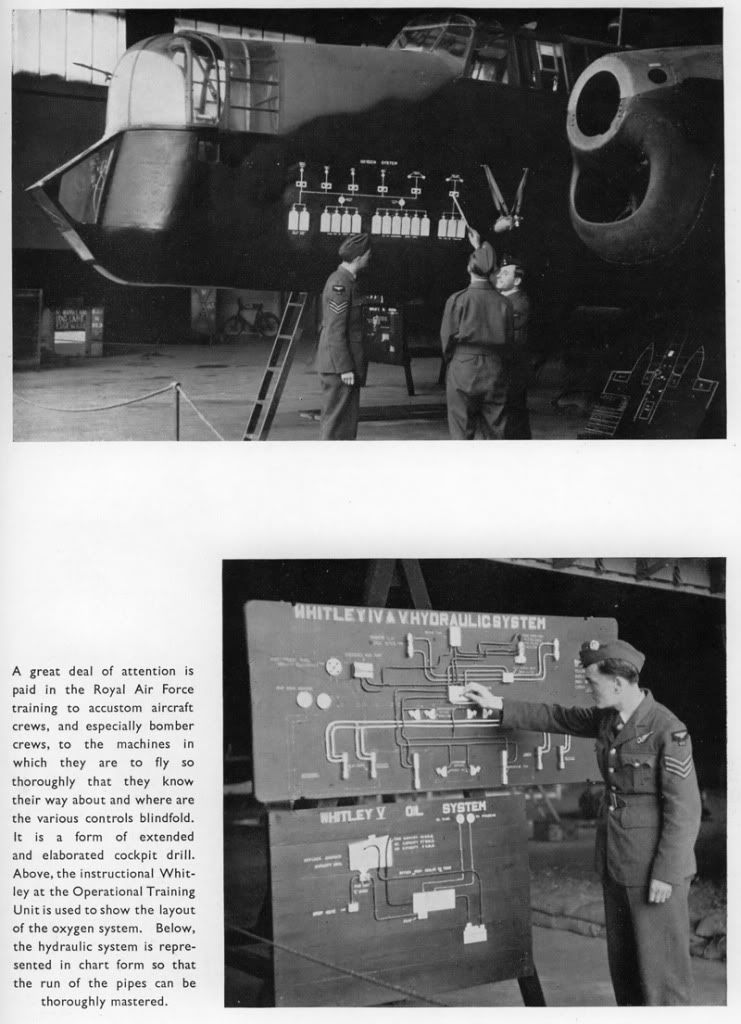

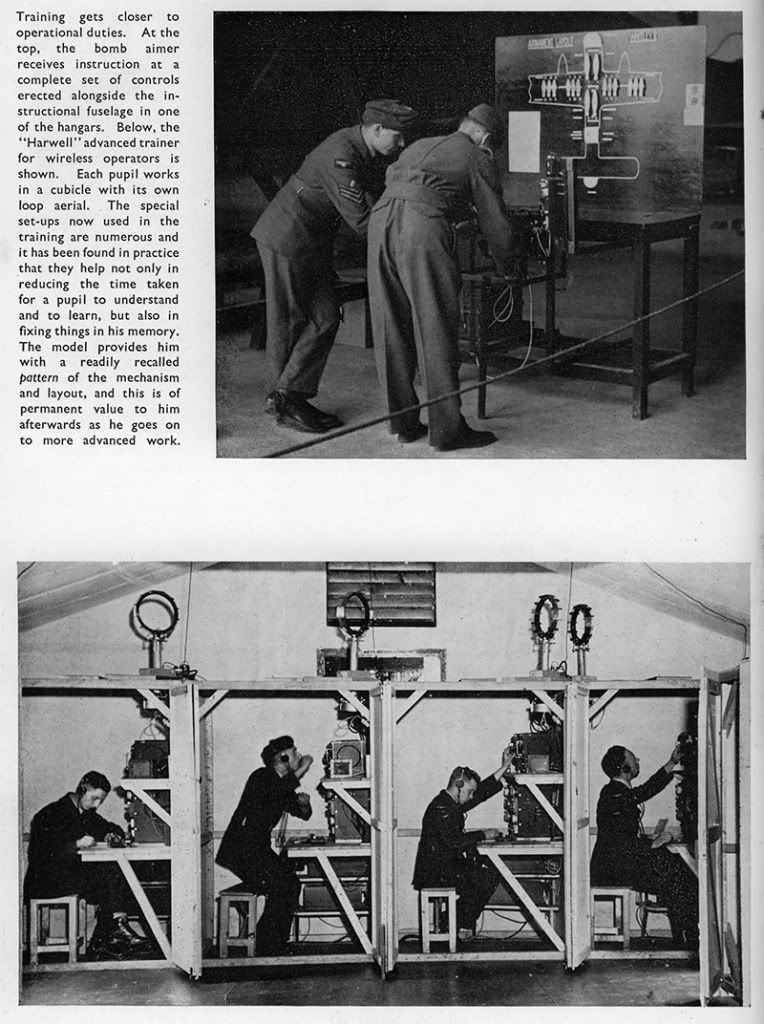

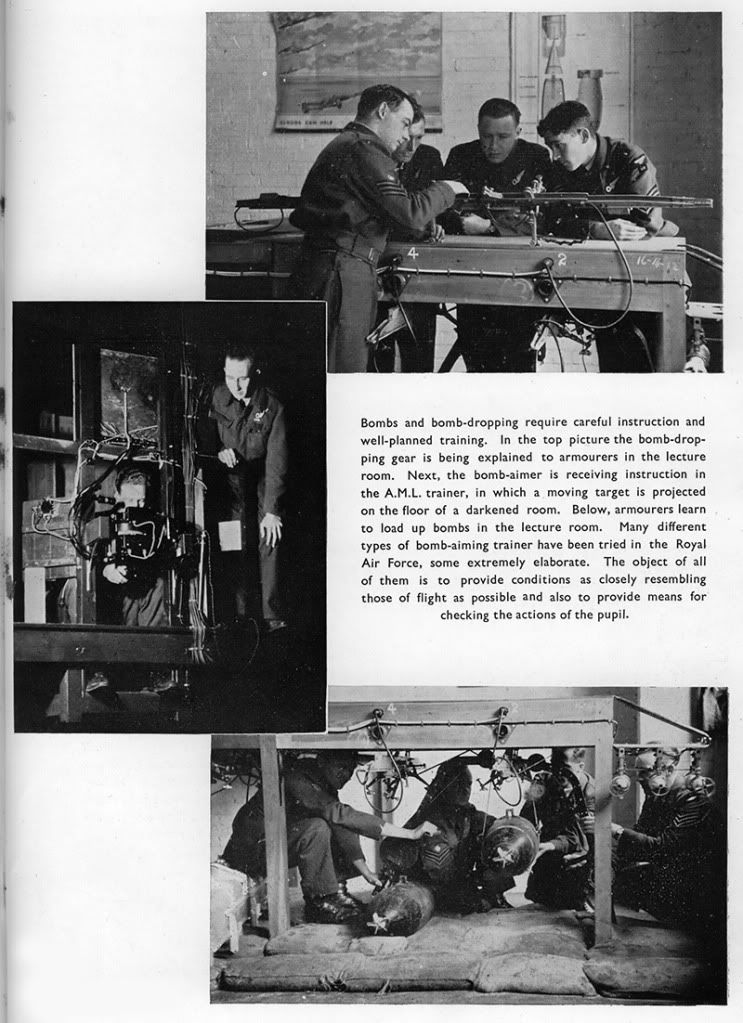

Part 67. January, 1941 RAID ON BREMEN BY A SERGEANT PILOT As you already know the RA.F. last week bombed military objectives in Bremen on three successive nights. I was on two of the three raids. I will describe my second one because it�s more vividly in my mind; in fact, I've never seen anything like it before. When we left there were so many fires in Bremen that I gave up counting them. We set off soon after tea-time: actually, I remember it was five-forty-six when we got on to the flarepath. The weather was very bad. We circled the aerodrome to get a bit of height: then almost immediately we had to climb through thick cloud, so that for the first half hour we were flying blind. Ice was forming on the windscreen and it looked as though we were going to have a bit of trouble so I started using my de-icers. But we came out of these bad conditions at seven thousand feet and above that it was beautiful weather�lovely and clear�with a quarter moon and plenty of stars. The only snag was that it was appallingly cold. In the ordinary way, I usually fly the aircraft out and fly it while we are doing the bombing: then when we've got clear of the target area, I hand over to the second pilot as far, say, as the North Sea: then I take over again. But this time it was so cold that we changed over several times both going out and coming back in order to try and get warm by moving about a bit. It'll give you some idea of what it was like, perhaps, when I tell you that once when I had some tea out of the thermos flask to try and warm myself up a little, there was ice at least an eighth of an inch thick round the rim of the cup when I'd finished drinking. But, apart from the cold, conditions were perfect. We got a bit of flak going over the Dutch coast but it wasn't really worth bothering about and I just carried on straight and level. So far as possible, I always try to keep a constant air speed going out and avoid jinking as much as possible�that's to say dodging about to avoid enemy fire�otherwise it only makes things more difficult for the navigator. Having got over this bit of flak quite safely we flew on steadily towards our target and without incident. When we were still about sixty miles away we could see a red glow in the sky, and thirty or forty miles off we could actually see flames rising above Bremen. We went in about five miles south of the target. I cut the engines as much as I could to avoid being picked up by the enemy, and of course, I was jinking now, all right. Then I did a very gentle left-hand circuit and I thought I'd try and count the fires as we were going round. I got up to thirty and then gave up. There must still have been at least another twenty or so in the target area. Some of the fires were very long in shape as though factories or other large long buildings were on fire. In one place there was a tremendous fire three or four hundred yards long. A deep red glow was reflected in the river and the fires were so numerous and so bright that they lit up the whole town, and my navigator was able to make his run up guided by the bridges across the river. As we were circling I saw three sticks of bombs go down. Then, just as we were starting our run up, the flak became rather more heavy ahead of us and I saw another bomber run�ning up, right across our track, but about a thousand feet above us and roughly half a mile ahead. This other plane was held in a large cone of searchlights: there must have been twenty-five or thirty lights on him. I could see his bombs leave the aircraft, and I was able to follow them for about five hundred feet as they fell. I didn't see them burst, though, because I was too intent on our own run up, but out of the corner of my eye I could see this other machine trying to get out of the searchlights: just wriggling one way and another. It was an amazing sight. Finally, the pilot did a stall turn and dived out of the lights. It was very good to see him get out of them so neatly. Then we did our bombing, mostly with incendiaries. I did another circuit to see what results we'd got, and I saw additional fires starting and several heavy explosions where our bombs had fallen. Altogether we were there about twenty minutes, during which time I'd seen four people bomb beside myself: that's to say a stick of bombs every four minutes. By this time the A.A. people had got our height fairly accurately and we had one or two bursts very near which rocked the plane, but we got out of it all right and started for home. When we were about ten miles away I turned to give the crew a look back at Bremen. The whole place seemed ablaze. Then again when we were about a hundred miles away I turned again and even from that distance I could still pick out a red glow in the sky from the direction of Bremen. I've been on fifteen raids, including Dusseldorf and Mannhein and Berlin, but I must say I have never seen anything like this one before. Training on the Whitley:

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3045230 - 07/03/10 07:00 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|

Part 68. Sorry it�s a day late RL interfering! January, 1941 TALK BY THE C.O. OF AN AUXILIARY FIGHTER SQUADRON The Squadron Leader Commanding No. 602 (City of Glasgow) Auxiliary Squadron, who is the author of the following account, has been with the squadron since the war. He was on patrol with it when it helped to bring down the first enemy bomber to be destroyed over England and he went south with the squadron when it moved to help in the defence of London as the "Blitz" began. Now the score of the squadron is eighty-nine enemy aircraft known to have been definitely destroyed and twenty-five more probably destroyed. AFTER four months' fighting in the South of England my squadron has just come out of the front line, as it were, to an aerodrome in a quieter part of the country up north. And it is good to be able to relax a bit. We have had our casualties in those four months, six pilots in the squadron were lost. But not one was actually killed in the air by the enemy. During this time scarcely a day passed without a combat. On many days we were sent up half a dozen times to fight battles, often against large formations of the enemy. In the circumstances we consider our losses were astonishingly light. On the other hand our "bag" of enemy aircraft was eighty-nine destroyed and confirmed, many probables and damaged. So the Germans paid a stiff price for our losses, and each new successful engagement gave us fresh heart for more. My unit is the City of Glasgow Squadron, one of several Auxiliary Squadrons which have been fighting in the south, and it might interest you to know how we come to be in this war, and what our experiences have been. The story perhaps will answer for similar squadrons from other parts of the country. I joined the squadron six years ago, shortly after leaving school, and began my flying career with them. The squadron had already been in existence for nine years, and for four years after my entry continued to engage in bomber training. Then, to the delight of every member, we became single-seater fighters. At once we got down to some really serious training. We had our civil occupa�tions to attend to, but every week-end and several evenings a week we put in learning all we could about fighter tactics. It was just as well we did, for six months after this development the war broke out. Within six weeks of hostilities, the squadron was engaged in the first Fighter Command action of the war� the raid on the Firth of Forth on October 16, 1939. In that action the squadron helped to shoot down the first enemy aircraft to be lost in the present war over British soil. I had nothing to do with it personally. In fact, I distinguished myself by being about the only person in the squadron who did not fire his guns at something Teutonic that day. Truth is, I never saw any German aircraft in the air while I was up. My record up till early this summer consisted of having seen two German aircraft in the air when I was on the ground, and two on the ground when I was in the air. But not one sausage did I see in the air while I was flying. One night in June, however, when I was on patrol, a Heinkel came my way�caught in the beams of several searchlights. This turned out to be my first victim. When the target aircraft is brightly illuminated, as this one was, it becomes fairly easy to shoot it down, as you have the advantage of seeing without being seen. The one difficulty I did find was to be able to gauge the height of the target, since there is no background to it. It looks like something sitting stationary in mid-air, when, in fact, it is travelling at 200 m.p.h. or there�abouts. After my debut, as one might call this combat, the squadron had several encounters with reconnaissance aircraft, mostly in ones and twos, over the North Sea. But it was not until my squadron moved south, sometime after I had been given command of it, that we encountered the real "Blitz". Soon after this, on one particular patrol, we were told to inter�cept a raid of about one hundred enemy aircraft which were coming in from the south. We were informed that their height was about 8,000 to 10,000 feet and that just about that height there was a heavy layer of cloud. Consequently we split into two flights. One flight, which I was leading, went above the clouds. The other remained below to make sure we did not miss the raid by being on the wrong side of the cloud layer. As you can well understand it is not possible for a pilot when flying an aircraft to hear any outside noises, and one has to rely entirely on seeing one's quarry. As it happened, on this occasion, we did hear something of our prey. The enemy were using a wireless frequency which must have been very nearly the same as our own, for presently we began to hear them chattering away to each other like a lot of monkeys in a box. Up to this time we had seen nothing of our quarry, and as we approached them the chatter grew louder and louder. Then, suddenly, we spotted them. They were straggled out in large "vicks" of about eighteen aircraft in each, just above the clouds. As we were only six in number, against their one hundred or so, we saw them a long time before they saw us�which, of course, gave us a big initial advantage. We were able to climb above them and get out in front of their leading formation. As we approached nearer, the Huns suddenly spotted us and, above all their chatter, a some�what agonized voice came through as clear as daylight�"Achtung. Achtung! Schpeetfiren!!" At that, an amazing transformation took place�and the straggling formation closed up into a formidable mass, the Me. 110s wheeling out from the front to form a protective circle round the bombers. Thanks to the advantage we had in position, three of us were able to dive head-on into the leading formation, whilst the other three stayed behind to play with the fighters. The leading forma�tion of bombers broke up after our attack, and in ones and twos they sought refuge either in or below the clouds. Those who were stupid enough to go below the layer of cloud were pounced on by our other flight which was still waiting for them. Theirs was a sort of vulture's job, and like vultures they did it. And then we all returned safely. Which reminds me. A very great friend of mine, who was one of the best fighter pilots in the country�but who unhappily was killed in action recently�once said to me: "You know, Napoleon used to say 'Don't give me clever men�give me lucky ones'." Well, there seems to be a good sprinkling of lucky ones in the R.A.F. Touch wood, I've been pretty lucky myself. I've forgotten how many combats I've fought. But, with a score of eight, confirmed, as a result of my fighting, I've never once been hit. Nor has my aircraft. Even more remarkable, another member of my squadron, with a score of twelve enemy aircraft to his credit, all confirmed, has never once been hit either. There was a dent on his tailplane one day, but it appears that the mark was caused by a stone. The best "bag" the squadron had in one single action was on a day in August when we were detailed to intercept a raid coming in over Dorset. Once again we had the advantage of height, and this time of the sun also, and arranged to knock down twelve of the enemy, with a loss to ourselves of only two aircraft�the pilots of both of them safe. The enemy were very strong in numbers, but they split up and fled back to France. One of the two pilots of my squadron who baled out, landed in a farmyard where he was promptly cornered by a lot of irate farmers armed with pitchforks. That reception, the pilot said, was much more frightening than the baling out. Actually, on that day, so many people were floating down by parachute at the same time�mostly Germans I'm glad to say�that it must have looked rather like an invasion army being landed. While on the subject of coming down by parachute a rather amusing incident occurred on another occasion. A very fat man baled out of a Dornier which the squadron had intercepted at about 25,000 feet. Needless to say everyone thought it was our old friend Goering doing another of his celebrated reconnaissance trips over this country! We circled around him while he was coming down�and it was ludicrous to see this enormously fat man dangling at the end of his parachute harness with his two podgy arms stretched above his head. His landing was even more ludicrous. He touched down on the roof of an outhouse in a garden in Kent, went crashing through the roof, and remained there with only his head sticking through. The last we saw of him was his parachute descending slowly on top of him, obscuring the whole picture. Finally, I would like to take this opportunity of saying a word about the ground crews. It is usually the pilots who get the praise and the thanks. But the job we do is little in comparison with the excellent and unremitting work done by the fellows who keep us in the air. They work for us day and night and I never hear a grumble from any of them. They are just grand, and if any of them are listening in just now I would like to say, speaking, I am sure, for all pilots, ""We take off our hats to them."  A Spitfire Mk Ia of 602 Squadron in early 1940. A de Havilland 3 blade propeller unit is fitted, along with a "blown" canopy and the laminated bullet proof windscreen and later aerial mast. The brass plate below the external starter plug can be seen on the side engine cowling.

Last edited by RedToo; 07/03/10 07:02 PM.

My 'Waiting for Clod' thread: http://tinyurl.com/bqxc9eeAlways take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.Elie Wiesel. Romanian born Jewish writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor. 1928 - 2016. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts. C.S. Lewis, 1898 - 1963.

|

|

#3048699 - 07/09/10 08:27 PM

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

Re: While we're waiting for BoB SoW: WWII BBC RAF Broadcasts

[Re: RedToo]

|

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

RedToo

Senior Member

|

Senior Member

Joined: Nov 2005

Posts: 3,070

Bolton UK

|